Archive : Article / Volume 1, Issue 1

- Case Report | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-8959/001

Adherence to Medication and Treatment Guidelines: Most Important but Mostly Despised

Alumni, Faculty of Pharmacy, Dhaka University, Bangladesh.

Abdul Kader Mohiuddin

Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, (2022). Adherence to Medication and Treatment Guidelines: Most Important but Mostly Despised. Journal of Clinical Sciences and Clinical Research. 1(1). DOI: 10.58489/2836-8959/001

© 2022 Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 03-12-2022

- Accepted Date: 14-12-2022

- Published Date: 23-12-2022

Patient compliance, Healthcare denials, Medication adherence, Elderly patient care, Treatment failure

Abstract

Proper use of medicine or taking medicine in correct order is essential to cure any disease. Even patients from developed nations have trouble staying on top of their drug compliance. When it comes to improper medicine use, there is an odd parallel between underdeveloped, emerging nations and the so-called developed world in the West. The key factor influencing whether patients stick to their treatment plan is their understanding and perception of the disease.

Introduction

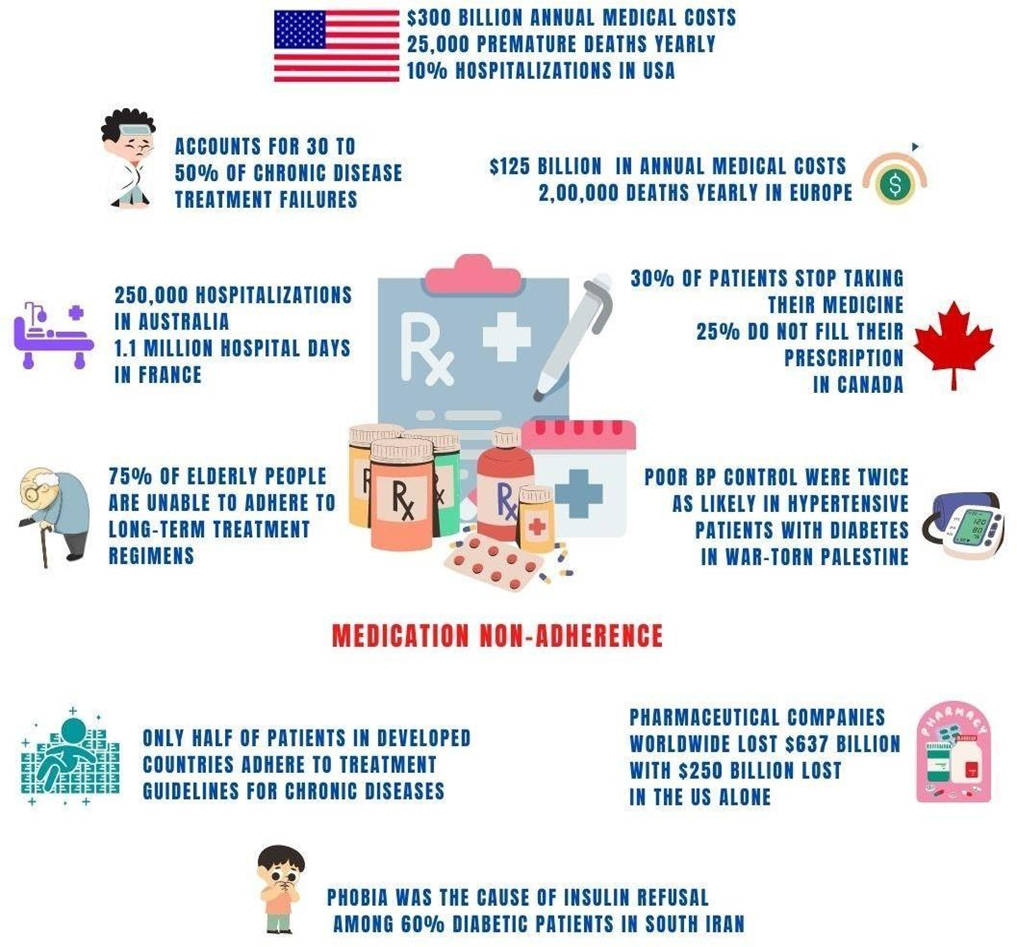

Proper use of medicine or taking medicine in correct order is essential to cure any disease. According to the WHO, lack of adherence to treatment regimens leads to major problems among patients, mostly with chronic illnesses. "Right administration" depends on at least 5 right factors--right patient, right drug, right time, right dose and right route [1]. "Medicines won't work if you don't take it right"--This simple fact is not understood by most people in the world, as a result still more than half of the patients with chronic diseases in the developed world do not take their medicine correctly-says WHO [2]. Patients with chronic diseases may find it particularly difficult to adhere because they frequently need to take their medications for an extended period of time, sometimes for the remainder of their lives. There are several reasons why patients may find it challenging to adhere to treatment regimens, and CDC estimates that medication non-compliance leads to 30 to 50% of chronic disease treatment failures. Poor adherence may cause treatment outcomes to not be achieved, symptoms to worsen, and one's health to deteriorate [3].

Non-Adherence in the so-called Developed Countries

In the UK, up to 50% of medicines are not taken as intended and 60% of NHS patients failed to receive the right treatment within 18 weeks [4-6]. Lack of medication adherence leads to poorer health outcomes, higher healthcare expenditures, increased hospitalizations, and even higher mortality rates in patients with chronic diseases [7]. Medication non-adherence alone accounts for at least 10% of hospitalizations in US, 250,000 hospitalizations in Australia and 1.1 million hospital days in France [8-10]; induces $300 billion in annual medical costs in US, and $125 billion in EU; causes more than 1,25,000 premature deaths in the US and 2,00,000 deaths in EU [8,11,12]. Also, two-thirds of medication-related hospital admissions in Australia are potentially preventable [9]. A recent Canadian study found that 30% of patients stop taking their medication before it is instructed, and 25% patients do not fill their prescription or take less than prescribed [13]. Among patients with at least one preventable encounter, medication non-adherence was associated with $679-$898 increased preventable spending [14]. However, pharmaceutical companies around the globe lost $637 billion in potential sales annually due to non-adherence, with $250 billion lost for the same in the U.S. alone last year [15].

Misuse of Antibiotics

More than half of the antibiotics worldwide are sold without a prescription and CDC stated, 30-50% of antibiotics prescribed in hospitals are inappropriate or unnecessary [16,17]. A recent study published by The Lancet, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust, states that nearly 5 million deaths worldwide in 2019 were related to bacterial resistance, which is expected to double by 2050 [18]. In south Asia, about 70% of hospitalized patients have been administered a minimum of one or more antibiotics, whereas 100% of ICU patients received antibiotics [19,20]. However, 70% to 80% of COVID-19 patients got different types of antibiotics for their COVID-19 treatment [21-23]. The most frequently prescribed antibiotics were azithromycin, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid [24]. In addition, it has been reported that about 90% of patients with COVID-19 are being unnecessarily treated with antibiotics and close to 100% of these prescriptions were empiric [25].

Abuse of NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19, Dengue, and Chikungunya

Globally, NSAIDs are responsible for at least 650,000 hospitalizations and 165,000 deaths and 30% of ADR related hospital admissions around the globe annually [26,27]. Overuse of this class of drugs can cause kidney injury, and their side effects can be 3 to 4 times higher in kidney compromised patients [28]. Many studies have reported widespread misuse of these drugs in Dengue, Chikungunya and Covid-19 patients. Especially in Dengue or Covid-19 patients, it is more important to maintain the hydration level of the body than to bring down the fever with the pain killers. In children, the use of excess Paracetamol syrup or suppositories may cause stomach irritation, which hampers digestion and led to vomiting and ended up with hospitalization. Most hospitalizations or ICU admissions among those patients could be prevented, with few exceptions, simply by preventing dehydration at home with saline and fruit juice or simply by drinking more water [29].

A New Era of Uncontrolled Use of Prescription Only and Recreational Drugs

More or less 40% of Covid-19 patients report sleep disturbances–use of Benzodiazepines in Covid-19 patients increases the incidence of delirium, depresses the system in patients with compromised respiratory functions, and contraindicated with some anti-viral medications [30,31]. Surprisingly, between 2020-2021, a huge increase in benzodiazepine dispensing is reported in Canada and abuse of similar drugs doubled in Italy [32]. Around 300 metric tons of morphine-type painkillers are used worldwide each year, less than 1% of which distributed to low-and-middle income countries, says the American Journal of Public Health [33]. So, their misuse and related side effects are also retained by the developed world. Prior to the US midterm elections, an announcement from authorities on "simple possession of cannabis" to thousands of convicted citizens exploded recreational drug abuse in both the US and the EU [34,35].

Negative Attitude towards Covid-19 Vaccine

A cross-sectional study of 259 school leaders in Hong Kong carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic between April 2021 and February 2022 shows that more than 50% of participants had limited health literacy, which was strongly associated with a negative attitude towards vaccination, confusion about COVID-19-related information and secondary symptoms [36]. Earlier, a US-based study in 2020 concluded that two-thirds of the Americans will not get the COVID-19 vaccine when it is first available, while 25% report that they do not have any intention to get vaccinated at any time [37]. In India, vaccine hesitancy was high in Tamil Nadu, more than 40% and willingness for vaccine uptake was found to be close to 90% in Kerala [38,39]. Another vaccine hesitancy survey by University College London, UK finds mistrust among 16% respondents, and 23% were confused [40].

Medical Cost and Low-Health-Literacy: The Two Major Barriers of Adherence among Diabetes Patients

A strange similarity can be found in under-developed, developing countries and the so-called developed world in the West or the Middle-East when it comes to not taking medicine properly. According to a WHO report, only half of patients in developed countries adhere to treatment guidelines for chronic diseases, which is much less in developing countries [41]. Several studies among diabetic patients in South Asian countries have shown that nearly half of patients do not adhere to their prescribed medication and are at risk of acute and long-term complications, resulting in increased hospitalization rates and medical costs [42,43]. “Medical costs are barriers to adherence to proper clinical guidelines for chronic diseases in poor countries” -- although discussed in many forums but forgetfulness, confusion about the duration required for medication use and mistrust about the overall efficacy of medication are among the reasons for non-adherence to diabetes management protocols in Middle Eastern countries [44]. Health literacy and medication adherence are strongly associated. Poor glycemic control due to low-health-literacy among diabetes patients reported to both South-East Asian and Middle Eastern countries [45-51].

Humanitarian crisis: Poor BP Control among Cardiac Patients

A recent study by the American Heart Association revealed that patients with high blood pressure do not follow treatment guidelines because of--(a) suboptimal dosing or prescribing the wrong medication (b) lack of insurance or lack of health care access and (c) patient failure to comply prescribed medication or other lifestyle guidelines [52]. Among hypertensive patients, less than 50% have persistent control over BP, even though more patients have received treatment over time. Furthermore, inadequate BP control was reported among those with elevated total cholesterol, LDL, and uric acid levels in both high-, low- and middle-income countries [53]. Humanitarian crisis is associated with increased short-term and long-term cardiac morbidity and mortality and increases in BP [54]. For example, hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus were twice as likely to exhibit poor BP control, found in war-torn Palestine [55]. Also, a US-based survey on re-settled Rohingya refugees from Myanmar shows a higher trend of chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension and obesity [56].

Superstitions: An Elephant in the Room

Epilepsy and schizophrenia still seen in most countries of the world as an evil spirit --although two-thirds of patients can become seizure-free with adequate treatment, poor adherence to proper guidelines is a major problem for effective recovery [57,58]. In a study conducted in India, 60% of the patients believed in luck and superstition with regard to illnesses [59]. Superstitions also reported in close to 40% men and 70% women in Northern Germany [60]. In Africa, 70% of people turn to indigenous treatments such as charms and witchery to treat their illness [61]. Surprisingly, more than 40% of Americans believe in spiritual treatments and researchers found that 73% of addiction treatment programs in the USA include a spirituality-based element [62,63]. Phobia was the cause of insulin refusal among 60% diabetic patients, despite physician recommendations—found in a study conducted in South Iran [64].

Pediatric and Geriatric Complications to Non-Adherence

Three-quarters of elderly patients worldwide are unable to adhere to appropriate long-term treatment regimens—due to multiple physical complications and additional medication burden [65]. Elderly patients taking at least 5 medications are at increased risk of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, falls, frailty, disability, and mortality, while ADRs are estimated to be 5% to 28% of acute geriatric medical admissions [66,67]. For children, common non-adherences are related to family routines, child-raising issues, and to social issues such as poverty. Long-term disease conditions like asthma, cystic fibrosis, HIV, diabetes, IBD and juvenile arthritis—are attributable to around 60% of non-adherence among children [68-70].

Exhibit 1. Several identified reasons for non-adherence to treatment guidelines for chronic diseases [7,71-73] | ||

No. | Status | Factors |

Patient's socio-economic status | Low health literacy, lack of family or social support network, unstable living or homelessness, financial insecurity | |

Treatment-related | Complexity and duration of treatment procedures, frequent changes in medication regimen, lack of immediate results, real or perceived unpleasant side effects, interference with lifestyle | |

Health system-related | High treatment costs, limited health system for patient education and follow-up, doctor-patient relationship, patient trust in health care, long waits, lack of patient information materials | |

Patient-related | Visual-hearing and cognitive impairment, mobility and dexterity, psychological and behavioral factors, perceived risk of disease susceptibility, superstitions and stigmatization by disease, etc | |

Conclusion

Finally, it can be said that patients' knowledge and perception of the disease is the main driving force in determining their adherence to the treatment regimen. Health care providers should explore providing more effective health-education to identify patients' attitudes toward disease, trust in medications, psychological stressors, and increase medication adherence.

Abbreviations:

Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR)

Blood Pressure (BP)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

World Health Organization (WHO)

Acknowledgement

I’m thankful to Dr. Daniel B. Mark, Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, North Carolina, USA for his valuable time to audit my paper and for his thoughtful suggestions. I’m also grateful to seminar library of Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Dhaka and BANSDOC Library, Bangladesh for providing me books, journal and newsletters.

Financial Disclosure or Funding:

N/A

Conflict of Interest:

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Informed Consent:

N/A

References

- Grissinger M. The Five Rights: A Destination Without a Map. P T. 2010 Oct;35(10):542.

- Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Apr;86(4):304-14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575.

- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. (n.d.). Why you need to take your medications as prescribed or instructed. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/special-features/why-you-need-take-your-medications-prescribed-or-instructed

- Barnett NLMedication adherence: where are we now? A UK perspective European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy: Science and Practice 2014; 21:181-184. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2013-000373

- Campbell, Denis, and Pamela Duncan. “Record 6.8m People Waiting for Hospital Treatment in England.” The Guardian, 8 Sept. 2022,

- Andrews, Luke. “60% of Patients Waiting 18 Wks for Treatment at Worst-performing Trust.” Mail Online, 7 Mar. 2022,

- Mohiuddin, A. K. “Chapter 14. Patient Compliance”. The Role of the Pharmacist in Patient Care: Achieving High Quality, Cost-Effective and Accessible Healthcare Through a Team-Based, Patient-Centered Approach, Universal-Publishers, 2020, pp. 250-270. https://www.universal-publishers.com/book.php?method=ISBN&book=1627343083

- Cutler RL, Torres-Robles A, Wiecek E, Drake B, Van der Linden N, Benrimoj SI, Garcia-Cardenas V. Pharmacist-led medication non-adherence intervention: reducing the economic burden placed on the Australian health care system. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019; 13:853-862 https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S191482

- Lim, Renly, et al. “The Extent of Medication-Related Hospital Admissions in Australia: A Review from 1988 to 2021.” Drug Safety, vol. 45, no. 3, 28 Jan. 2022, pp. 249–257., https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-021-01144-1.

- “Medication Nonadherence: Medicine's Weakest Link.” Wolters Kluwer, Health/Experts Insight, 13 Feb. 2020,

- Kardas, Przemysław et al. “Reimbursed medication adherence enhancing interventions in 12 european countries: Current state of the art and future challenges.” Frontiers in pharmacology vol. 13 944829. 11 Aug. 2022, doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.944829

- van Boven JF, Tsiligianni I, Potočnjak I, Mihajlović J, Dima AL, Nabergoj Makovec U, Ágh T, Kardas P, Ghiciuc CM, Petrova G, Bitterman N, Kamberi F, Culig J, Wettermark B. European Network to Advance Best Practices and Technology on Medication Adherence: Mission Statement. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Oct 11; 12:748702. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.748702.

- Bonsu KO, Young S, Lee T, Nguyen H, Chitsike RS. Adherence to Antithrombotic Therapy for Patients Attending a Multidisciplinary Thrombosis Service in Canada - A Cross-Sectional Survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022 Jul 26; 16:1771-1780. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S367105.

- Zhang Y, Flory JH, Bao Y. Chronic Medication Nonadherence and Potentially Preventable Healthcare Utilization and Spending Among Medicare Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Nov;37(14):3645-3652. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07334-y.

- Bulik, Beth Snyder. “Nonadherence Costs Pharma $600B-plus in Annual Sales: Study.” Fierce Pharma, 22 Nov. 2016,

- Bahta M, Tesfamariam S, Weldemariam DG, Yemane H, Tesfamariam EH, Alem T, Russom M. Dispensing of antibiotics without prescription and associated factors in drug retail outlets of Eritrea: A simulated client method. PLoS One. 2020 Jan 24;15(1): e0228013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228013.

- “Improve Antibiotic Use.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 9 Mar. 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/sixeighteen/hai/index.htm.

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022 Feb 12;399(10325):629-655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0.

- Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfection in individuals with coronavirus: a rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71:2459-2468.

- Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. Coronavirus disease 2019, superinfections, and antimicrobial development: what can we expect? Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 71:2736-2743

- Daria, Sohel, and Md Rabiul Islam. “Indiscriminate Use of Antibiotics for COVID-19 Treatment in South Asian Countries is a Threat for Future Pandemics Due to Antibiotic Resistance.” Clinical pathology (Thousand Oaks, Ventura County, Calif.) vol. 15 2632010X221099889. 18 May. 2022, doi:10.1177/2632010X221099889

- Langford B.J., So M., Raybardhan S., Leung V., Soucy J.R., Westwood D., Daneman N., MacFadden D.R. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: Rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021; 27:520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.018.

- Cong W., Poudel A.N., Alhusein N., Wang H., Yao G., Lambert H. Antimicrobial Use in COVID-19 Patients in the First Phase of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics. 2021; 10:745. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10060745.

- Kamara, Ibrahim Franklyn et al. “Antibiotic Use in Suspected and Confirmed COVID-19 Patients Admitted to Health Facilities in Sierra Leone in 2020-2021: Practice Does Not Follow Policy.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 19,7 4005. 28 Mar. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijerph19074005

- Usman M, Farooq M, Hanna K. Environmental side effects of the injudicious use of antimicrobials in the era of COVID-19. Sci Total Environ. 2020; 745:141053. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141053.

- Kasciuškevičiūtė S, Gumbrevičius G, Vendzelytė A, Ščiupokas A, Petrikonis K, Kaduševičius E. Impact of the World Health Organization Pain Treatment Guidelines and the European Medicines Agency Safety Recommendations on Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in Lithuania: An Observational Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2018 May 11;54(2):30. doi: 10.3390/medicina54020030.

- Davis, Abigail, and John Robson. “The Dangers of NSAIDs: Look Both Ways.” British Journal of General Practice, vol. 66, no. 645, 2016, pp. 172–173.,

- Lucas GNC, Leitão ACC, Alencar RL, Xavier RMF, Daher EF, Silva Junior GBD. Pathophysiological aspects of nephropathy caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bras Nefrol. 2019 Jan-Mar;41(1):124-130. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2018-0107.

- Mohiuddin, Abdul Kader. “Taking Medicine in the Right Way: Most Important but Most Neglected.” Cases, vol. 1, no. 1, 13 Nov. 2022, pp. 1–3., https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.35702/cases.10003. https://www.jcases.org/articles/taking-medicine-in-the-right-way-most-important-but-most-neglected.pdf

- Jahrami H, BaHammam AS, Bragazzi NL, Saif Z, Faris M, Vitiello MV. Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Feb 1;17(2):299-313. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8930.

- Ostuzzi G, Papola D, Gastaldon C, Schoretsanitis G, Bertolini F, Amaddeo F, Cuomo A, Emsley R, Fagiolini A, Imperadore G, Kishimoto T, Michencigh G, Nosé M, Purgato M, Dursun S, Stubbs B, Taylor D, Thornicroft G, Ward PB, Hiemke C, Correll CU, Barbui C. Safety of psychotropic medications in people with COVID-19: evidence review and practical recommendations. BMC Med. 2020 Jul 15;18(1):215. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01685-9.

- Sarangi, Ashish et al. “Benzodiazepine Misuse: An Epidemic Within a Pandemic.” Cureus vol. 13,6 e15816. 21 Jun. 2021, doi:10.7759/cureus.15816

- Bhadelia A, De Lima L, Arreola-Ornelas H, Kwete XJ, Rodriguez NM, Knaul FM. Solving the Global Crisis in Access to Pain Relief: Lessons from Country Actions. Am J Public Health. 2019 Jan;109(1):58-60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304769

- Lopez, German. “Marijuana Majority/ Americans Support Marijuana Legalization, but Many of Their Political Leaders Do Not.” The NewYork Times, 23 Nov. 2022.

- Oltermann, Philip. “Germany Announces Plan to Legalise Cannabis for Recreational Use.” The Guardian, 26 Oct. 2022,

- Shahid, Rabia et al. “Impact of low health literacy on patients' health outcomes: a multicenter cohort study.” BMC health services research vol. 22,1 1148. 12 Sep. 2022, doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08527-9

- Alam, Md Moddassir et al. “Public Attitude Towards COVID-19 Vaccination: Validation of COVID-Vaccination Attitude Scale (C-VAS).” Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare vol. 15 941-954. 29 Apr. 2022, doi:10.2147/JMDH.S353594

- Danabal, K.G.M., Magesh, S.S., Saravanan, S. et al. Attitude towards COVID 19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy in urban and rural communities in Tamil Nadu, India – a community-based survey. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 994 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07037-4

- Leelavathy, Manju et al. “Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination among the public in Kerala: A cross sectional study.” Journal of family medicine and primary care vol. 10,11 (2021): 4147-4152. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_583_21

- Paul, Elise et al. “Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications.” The Lancet regional health. Europe vol. 1 (2021): 100012. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100012

- Chauke GD, Nakwafila O, Chibi B, Sartorius B, Mashamba-Thompson T. Factors influencing poor medication adherence amongst patients with chronic disease in low-and-middle-income countries: A systematic scoping review. Heliyon. 2022 Jun 15;8(6):e09716. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon. 2022.e09716.

- Chong E, Wang H, King-Shier KM, Quan H, Rabi DM, Khan NA. Prescribing patterns and adherence to medication among South-Asian, Chinese and white people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Diabet Med. 2014. August 11 10.1111/dme.12559

- Sohal T, Sohal P, King-Shier KM, Khan NA. Barriers and Facilitators for Type-2 Diabetes Management in South Asians: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015 Sep 18;10(9): e0136202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136202.

- Alsairafi ZK, Taylor KM, Smith FJ, Alattar AT. Patients' management of type 2 diabetes in Middle Eastern countries: review of studies. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016 Jun 10; 10:1051-62. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S104335.

- Almigbal, Turky H et al. “Association of health literacy and self-management practices and psychological factor among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia.” Saudi medical journal vol. 40,11 (2019): 1158-1166. doi:10.15537/smj.2019.11.24585

- Nair, Satish Chandrasekhar et al. “Health literacy in a high-income Arab country: A nation-wide cross-sectional survey study.” PloS one vol. 17,10 e0275579. 5 Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275579

- Hashim, Saman Agad et al. “Association of Health Literacy and Nutritional Status Assessment with Glycemic Control in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” Nutrients vol. 12,10 3152. 15 Oct. 2020, doi:10.3390/nu12103152

- Hussein, Shaimaa H et al. “Association of health literacy and other risk factors with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes in Kuwait: A cross-sectional study.” Primary care diabetes vol. 15,3 (2021): 571-577. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2021.01.011

- Khatiwada, Bhushan, et al. “Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Health Literacy among People with Noncommunicable Diseases (Ncds) in South Asian Countries: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, vol. 18, 3 Nov. 2022, p. 101174., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2022.101174.

- Rajah R., Hassali M.A.A., Murugiah M.K. A systematic review of the prevalence of limited health literacy in Southeast Asian countries. Public Health. 2019; 167:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.028.

- Saleh, Ariyanti, et al. “The Relationships among Self-Efficacy, Health Literacy, Self-Care and Glycemic Control in Older People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” Working with Older People, vol. 25, no. 2, 4 May 2021, pp. 164–169., https://doi.org/10.1108/wwop-08-2020-0044.

- Choudhry NK, Kronish IM, Vongpatanasin W, Ferdinand KC, Pavlik VN, Egan BM, Schoenthaler A, Houston Miller N, Hyman DJ; American Heart Association Council on Hypertension; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Medication Adherence and Blood Pressure Control: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2022 Jan;79(1):e1-e14. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000203.

- Elnaem, Mohamed Hassan et al. “Disparities in Prevalence and Barriers to Hypertension Control: A Systematic Review.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 19,21 14571. 6 Nov. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijerph192114571

- Keasley, James et al. “A systematic review of the burden of hypertension, access to services and patient views of hypertension in humanitarian crisis settings.” BMJ global health vol. 5,11 (2020): e002440. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002440

- Alawneh, Issa S et al. “The Prevalence of Uncontrolled Hypertension among Patients Taking Antihypertensive Medications and the Associated Risk Factors in North Palestine: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Advances in medicine vol. 2022 5319756. 25 Aug. 2022, doi:10.1155/2022/5319756

- Rahman, Ayesha, et al. “Non-Communicable Diseases Risk Factors among the Forcefully Displaced Rohingya Population in Bangladesh.” PLOS Global Public Health, vol. 2, no. 9, 27 Sept. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000930.

- Lossius, M. I., Alfstad, K. Å., Aaberg, K. M., & Nakken, K. O. (2017). Seponering av Antiepileptika Ved anfallsfrihet – når og hvordan? Tidsskrift for Den Norske Legeforening, 137(6), 451–454. https://doi.org/10.4045/tidsskr.16.0957

- Yang, D. Zhonghua shen jing jing shen ke za zhi = Chinese journal of neurology and psychiatry vol. 25,4 (1992): 215-8, 253.

- Banerjee S, Varma RP. Factors affecting non-adherence among patients diagnosed with unipolar depression in a psychiatric department of a tertiary hospital in Kolkata, India. Depress Res Treat. 2013; 2013:809542.

- Graeupner D, Coman A. The dark side of meaning-making:How social exclusion leads to superstitious thinking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2017; 69:218–22.

- Puckree T, Mkhize M, Mgobhozi Z, Lin J. African traditional healers:What health care professionals need to know. Int J Rehabil Res. 2002; 25:247–51.

- Taher, Mohammad et al. “Superstition in health beliefs: Concept exploration and development.” Journal of family medicine and primary care vol. 9,3 1325-1330. 26 Mar. 2020, doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_871_19

- Grim, Brian J, and Melissa E Grim. “Belief, Behavior, and Belonging: How Faith is Indispensable in Preventing and Recovering from Substance Abuse.” Journal of religion and health vol. 58,5 (2019): 1713-1750. doi:10.1007/s10943-019-00876-w

- Mirahmadizadeh, Alireza et al. “Factors Affecting Insulin Compliance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in South Iran, 2017: We Are Faced with Insulin Phobia.” Iranian journal of medical sciences vol. 44,3 (2019): 204-213.

- Félix IB, Henriques A. Medication adherence and related determinants in older people with multimorbidity: a cross‐sectional study. Nurs Forum. 2021; 56:834–843. doi:10.1111/nuf.12619

- Chippa, Venu, and Kamalika Roy. “Geriatric Cognitive Decline and Polypharmacy.” National Library of Medicine, StatPearls Publishing, Jan. 2022,

- Varghese D, Ishida C, Haseer Koya H. Polypharmacy. National Library of Medicine, StatPearls Publishing, Jan. 2022.

- Santer, Miriam et al. “Treatment non-adherence in pediatric long-term medical conditions: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies of caregivers' views.” BMC pediatrics vol. 14 63. 4 Mar. 2014, doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-63

- Al-Hassany, Linda et al. “Assessing methods of measuring medication adherence in chronically ill children-a narrative review.” Patient preference and adherence vol. 13 1175-1189. 22 Jul. 2019, doi:10.2147/PPA.S200058

- Wu, Y Y et al. Zhonghua er ke za zhi = Chinese journal of pediatrics vol. 60,11 (2022): 1191-1195. doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20220110-00036

- Jin J, Sklar GE, Min Sen Oh V, Chuen Li S. Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient's perspective. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008 Feb;4(1):269-86. doi: 10.2147/tcrm. s1458.

- Wilder, Marcee E et al. “The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Journal of general internal medicine vol. 36,5 (2021): 1359-1370. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06447-0

- Kardas, Przemyslaw et al. “Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews.” Frontiers in pharmacology vol. 4 91. 25 Jul. 2013, doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00091

Quick links

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Non-Adherence in the so-called Developed Countries

- Misuse of Antibiotics

- Abuse of NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19, Dengue, and Chikungunya

- A New Era of Uncontrolled Use of Prescription Only and Recreational Drugs

- Negative Attitude towards Covid-19 Vaccine

- Medical Cost and Low-Health-Literacy: The Two Major Barriers of Adherence among Diabetes Patients

- Humanitarian crisis: Poor BP Control among Cardiac Patients

- Superstitions: An Elephant in the Room

- Pediatric and Geriatric Complications to Non-Adherence

- Conclusion

- Abbreviations:

- Acknowledgement

- Financial Disclosure or Funding:

- Conflict of Interest:

- Informed Consent:

- References