Archive : Article / Volume 3, Issue 2

- Research Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-3558/023

Examining the State of Suicidality in Youth and Young Adults: A Scoping Review of the Literature on Suicidality across Muslim and Arab Countries from January 2000 to March 2024

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

2Department of Neuroscience, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

3Healthy Active Living & Obesity (HALO) Research Group, Childrenâs Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario Canada

4The Clinical Epidemiology Program, The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, ON, Canada

5Department of Psychiatry, Western University, London, ON, Canada

6Department of Neuroscience, Princes Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

7Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

8Department of Psychiatry, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

9Youth Psychiatry Program, Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Kevin R. Simas, B. A*

Kevin R. Simas, et.al. (2024). Examining the State of Suicidality in Youth and Young Adults: A Scoping Review of the Literature on Suicidality across Muslim and Arab Countries from January 2000 to March 2024. Psychiatry and Psychological Disorders. 3(2); DOI: 10.58489/2836-3558/023

© 2024 Kevin R. Simas, this is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 26-06-2024

- Accepted Date: 25-07-2024

- Published Date: 27-07-2024

suicide, child, adolescent, protective factors, risk factors.

Abstract

Objective: Suicide is a global concern and one of the leading causes of death among youth. This systematic review aims to summarize the current state of literature on suicidality rates and known risk and protective factors among youth in Muslim and Arab countries.

Method: A comprehensive search strategy was employed through Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Proquest Dissertations & Theses Global, and Web of Science, from January 2000 to March 2024. Articles were included if they examined youth up to 18 years of age who had reported mental health conditions.

Results: 14 articles met the inclusion criteria. The findings revealed that suicide mortality rates in Muslim and Arab youth ranged from 0.5% to 8.9%. Suicide attempt rates varied from 4.3% to 11.4% across different countries. Risk factors for suicidality included anxiety, depression, stress, abuse or bullying, family issues, smoking, low socioeconomic status, guilt and shame, and loneliness/isolation. Protective factors identified were higher socioeconomic status, satisfaction with social life, a sense of belonging, coping strategies, strong family environments, and religious beliefs. Gender-specific differences were limited, and more research is needed to explore this aspect.

Conclusion: The study highlights the need for improved reporting of suicide data and more comprehensive research focusing on younger populations. Understanding suicidality rates and culturally specific risk and protective factors is crucial for effective suicide prevention and treatment strategies among youth in these regions. Further research is warranted to address the limitations and gaps in the current literature.

Highlights

- This systematic review aims to summarize the current state of literature on suicidality rates and known risk and protective factors among youth in Muslim and Arab countries.

- Suicide mortality rates in Muslim and Arab youth ranged from 0.5% to 8.9%. Suicide attempt rates varied from 4.3% to 11.4% across different countries.

- Understanding suicidality rates and culturally specific risk and protective factors is crucial for effective suicide prevention and treatment strategies among youth in these regions. These concepts are discussed in this article.

Introduction

Recognized as a worldwide leading cause of mortality across all ages, suicide is a modern-day health concern in youth. With over 700 000 deaths by suicide every year, suicide impacts many individuals and families across the globe [1]. Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death in those aged 10-24 [2]. Suicide is associated with several other mental health conditions, including anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder [3]. Suicide in middle eastern youth has great variability depending on the country. While global suicide rates have decreased steadily from 2000 to 2019 (from 14.0 to 9.0 per 100 000), 77% of these cases occurred in low to middle-income countries, including many Muslim countries [4]. For reference, North American countries such as Canada and the United States have rates of 5.01 and 5.91 respectively, with an overall worldwide rate of 3.77 per 100 000 people.

Despite the high prevalence of suicide and comorbid mental health disorders in Middle Eastern countries, this area is understudied compared to more developed countries [5]. This is of significant importance given the higher morbidity and mortality rates in Arab youth. Depression and mental disorders make up nearly 25% of the Arab adolescent disability [6]. While Arabs constitute the largest ethnic group of the Middle East, it is a large heterogenous mosaic that includes other groups such as various Iranian and Turkic people. The underreporting and lack of research may be related to how suicide and mental health are viewed in the Middle East [7]. According to the Holy Quran, the central religious text of Islam which applies to most Muslims, suicide is considered a homicide [8]. Suicide is also viewed as a sin, and in some countries such as Kuwait, Syria, and Pakistan, it is a criminal offence. The criminalization of suicide and the shame associated with the act poses a challenge for individuals struggling with mental health who feel they cannot seek help. Additionally, families of those who commit suicide may be exposed to ostracism and possible social sanctions within their communities [9]. Some studies have found religion to be a protective factor against suicide due to these Islamic principles. Moreover, some studies have reported suicide rates to be lower in countries where Islam is the predominant religion [4]. However, these rates could be due to an underreporting of deaths by suicide [7].

It has been consistently reported that suicide rates are higher for males, while rates of suicide attempts are more common among females [10]. This trend also holds across the Middle East [8,11]. The highest female rates have also been found in Iranian women aged 15-24 years of age [12].

Unemployment has been found to be the strongest risk factor for the high suicide rates in this country [4].Many of the existing literature and review studies focus on all ages or strictly adults as opposed to youth and adolescents in Muslim countries. A recent study highlighted suicidal behaviour amongst students living in Muslim-majority countries, with most of their population being university students [13]. The objective of the present study is to provide an overview on prevalence rates of suicide and suicide attempts in Muslim children as well as adults in the Arab World, while concurrently identifying gaps in the literature in this area. Identified risk and protective factors for this population will also be reviewed and discussed.

Methods

Given that relevant reviews on this topic have not been recently published, we used a systematic review as an appropriate starting point to summarize the current state of literature available on suicidality rates and known risk and protective factors in youth across Muslim and Arab countries, as well as to provide a means for future systematic literature reviews on this topic to build off from.

Search strategy: A comprehensive search strategy was designed and implemented for an exhaustive search of relevant literature. The search was conducted by an information specialist at the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre. The search strategy targeted articles with key terms in their respective titles and abstracts. Peer-reviewed articles published between January 2000 and March 2024 were systematically identified from Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Proquest Dissertations & Theses Global, and Web of Science. Key terms were grouped according to the following categories: outcome variables, demographic, and age. Within each category search terms were separated using the Boolean operator “OR”, and independent categories were linked together with the Boolean operator “AND”. (Suicide OR Suicide attempted OR suicide completed) AND (Muslim OR Arab) AND (Children OR Adolescent OR Youth OR Teen).

Eligibility Criteria: Studies were selected if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) original peer-reviewed articles written in English, (2) study focuses on Muslim and Countries with Arab demographic, (3) includes a patient population aged 25 and under, and (4) reported patient data on either completed suicide, self-harm with suicidal ideation, suicide protective and/or risk factors. Studies were excluded if they met the following exclusion criteria: (1) studies were not original peer-reviewed articles or were in a foreign language, (2) population were adults only, (3) reported behaviours of self-harm with no suicidal ideation. (Note that we define Muslim and Arab countries as those defined to geographically carry a predominant Muslim or Arabic population as applicable, such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iran).

Selection Procedure: All articles adhered to the same selection procedure and inclusion and exclusion criteria. During the process of selecting eligible studies, duplicates and foreign-language titles were removed where applicable. Excluded from consideration were essays or reports that document on the subject matter, non-peer-reviewed theses and dissertations, grey literature, editorial comments, and narratives. Articles were then screened for content. This process encompassed a two-stage screening process: the first screening step involved an article title and abstract review; the second screening step involved a full text review. During these screening steps, any contraindication to our inclusion and exclusion criteria or being unable to access the full-text resulted in the article being ineligible for review.

Data Extraction and Synthesis:

Once all eligible articles were selected to be included in this review, pdf copies of the articles were then reviewed, and data was manually extracted and entered into an appropriate spreadsheet database. Data was extracted for the following study characteristics: Author, year, title, journal, country, study design, suicide prevalence, suicide prevalence by gender, overall suicide attempt prevalence and suicide attempt prevalence by gender, risk factors, and protective factors. Raw prevalence rates and general conclusive findings, where appropriate, were summarized as per author reporting. Collation of this data formed the basis of the results section and summary tables.

Results

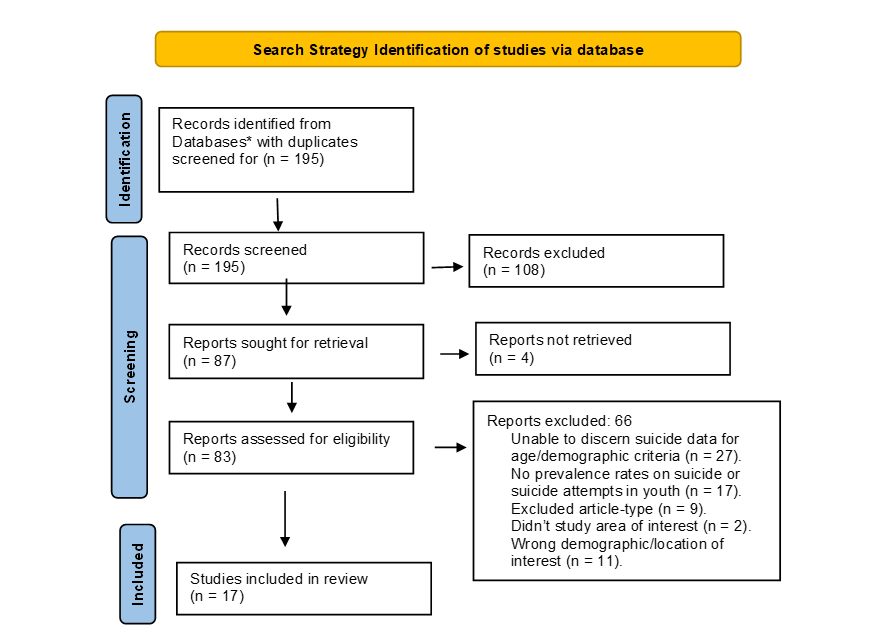

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. (2020) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews

*Databases searched include Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Proquest Dissertations & Theses Global, and Web of Science.

Fig 1: PRISMA flow diagram of the search and study selection process

Literature Search:

Our search strategy yielded 195 studies in which 108 studies were excluded based on a title and abstract screening with our inclusion/exclusion criteria. This resulted in 87 studies that were sought for full-text retrieval, in which 4 full-texts were not retrieved, thus resulting in 83 full-text studies being reviewed and screened for content eligibility. A total of 66 studies were excluded: 27 studies were excluded due to being unable to discern suicide data for age or demographic criteria, 17 studies were excluded due to no reported relevant prevalence rates on suicide or suicide attempts in youth, 9 studies were excluded due to falling under the category of either an essay or report, non-peer-reviewed thesis or dissertation, grey literature, editorial comment, or narrative that documents on the subject matter, 2 studies were excluded due to being the incorrect study area of interest, and 10 studies were excluded due to being focusing on the wrong location/demographic of interest. The results yielded a total of 17 articles14-30 which were included in our systematic review. Figure 1 provides a visual of the search and study selection process and results.

Summary of Results

Suicide rates

The prevalence of suicide mortality rates in Muslim and Arab youth ranged from 0.5% to 8.9%. Rates amongst youth males and females for completed suicide were similar in rates when compared across younger and older youth ages and became more prevalent after the age of 15 across both youth males and females. (See Table 1).

Table 1. Quantitative Studies Reporting Suicide Rates

Author/ Date | Location | Sample | Methodology | Overall Prevalence | Prevalence (Male) | Prevalence (Female) |

| Al Madni, O.M, et al. (2010) | Saudi Arabia | Hanging deaths from 10->70 y/o. | Retrospective Analysis | Of 133 cases, 2.25% was 10-19 y/o. | N/A. | N/A. |

| Azmak, A. D. (2006) | Turkey | 14-95 y/o | Retrospective Analysis | Of 137 autopsied suicide cases, 12 (8.9%) were 14-19 y/o. | 7/12 were male | 5/12 were female. |

| Dervic K., et al., (2012) | Dubai, United Arab Emirates | Sampled all ages of the expatriate population, but 0-18 was isolated | Retrospective Analysis | Of 594 cases, 3 (0.5%) were younger than 18. | N/A. | N/A. |

| Koronfel A. A., et al (2002) | Dubai, United Arab Emirates | Sampled all population, <20> | Retrospective Analysis | Of 362 suicide cases, 22 were under 20 years of age. Total cases autopsied were 4269. | 14/22 | 8/22 |

| Snowdon J., et al. (2020) | Islamic Republic of Iran | Sampled all population, 10-19 was isolated. | Retrospective Analysis | N/A. | For rates per 100, 000 people,

| For rates per 100, 000 people, 2006-2010:

2011-2015:

|

Suicide attempt rates:

Suicide attempt rates in Muslim and Arab youth varied from 4.3% to 30percent depending on the country. (See Table 2).

Table 2. Quantitative Studies Reporting Suicide Attempt Prevalence Rates

| Author/Date | Location | Sample | Methodology | Overall Prevalence | Prevalence (Male) | Prevalence (Female) |

| Baroud E., et al. (2019) | Lebanon | Adolescents | Secondary Analysis of Survey Design | In a representative sample of adolescents from the Greater Beirut area, of 510 participants, 4.3% reported experiencing suicidal ideation or attempt. | N/A. | N/A. |

| Ibrahim H., et al., (2021) | United Arab Emirates | Youth 13-17 | Survey | The overall prevalence of suicide ideation, planning and attempts were 14.6% (95% CI: 13.4–15.8%), 11.8% (95% CI: 10.7–12.9%) and 11.4% (95% CI: 10.3–12.5%), respectively. | N/A. | N/A. |

| Mirza S., et al., (2024) | Pakistan | Sampled all population, <18> | Survey | In the age group <18> | N/A. | N/A. |

| Sawalha A. F. (2012) | Palestine | Sampled all admissions but isolated <18> | Retrospective Analysis | Less than one-third of the patients (16; 29.6%) were under 18 years of age. | N/A. | N/A. |

| Siddik M. A. B., et al., (2024) | Bangledash | Youth 18-23, sexual abuse survivors | Survey | Of 61 respondents, 21.31% of participants had attempted suicide at least once. | N/A. | N/A. |

| Vally Z., et al., (2023) | United Arab Emirates | Youth 11-18 | Survey | Of 5826 respondents, 30% had attempted suicide. | N/A. | N/A. |

Table 3. Quantitative Studies Suicide Risk Factors

| Author/Date | Location | Sample | Methodology | Risk Factor | Other |

| Baroud E., et al. (2019) | Lebanon | Adolescents | Secondary Analysis of Survey Design |

|

|

| Copeland, M., et al. (2021) | Saudi Arabia | Youth 15-19 | Survey |

| |

| Dardas L. A., et al., (2020) | Jordan | Youth 14-17 | Descriptive Qualitative Design | The data revealed several risks for suicide among adolescent participants, including depression, anxiety, stigma, shame and isolation, family issues, life pressures, and guilt. | |

| Dehnel R., et al., (2023) | Jordan | Youth 10-17 | Survey | A child who experienced bullying was 2.18 times more likely than a child who was not perceived as being bullied to have suicidal ideation. Age was found to be a risk factor, with younger children more at risk. Depression levels were a predictor of suicidality. | |

| Ibrahim H., et al., (2021) | United Arab Emirates | Youth 13-17 | Survey | Age was consistently associated with the three suicide outcomes, with older age showing higher risk of suicidality. | |

| Mirza S., et al., (2024) | Pakistan | All population sampled, <18> | Survey | Statistically significant risk factors for those <18> | |

| Siddik M. A. B., et al., (2024) | Bangledash | Youth 18-23, sexual abuse survivors | Survey | Participants who had been physically abused were 5.1 times more likely to have suicide incidents. | |

| Vally Z., et al., (2023) | United Arab Emirates | Youth 11-18 | Survey | Risk factors associated with suicidal behaviour include anxiety, loneliness, and cigarette use. | |

| Yildiz, M. (2015) | Turkey | Youth 13-17 | Retrospective Analysis | (parent strain, school strain, peer strain, economic strain, negative life events strain, and physical victimization strain). All of the adolescent-reported strains with the exception of peer strain were significantly associated with adolescent suicidal ideation. all of the adolescent-reported strains with the exception of economic strain were significantly associated with adolescent suicidal attempt. | |

| Yuksek D. (2021) | Turkey | Highschool students, 9-10 grade. | Survey | Suicidal suggestion (b = .821; p < .001), and depression (b = .062; p < .001) to significantly be associated with suicide attempts. Adolescents with the highest levels of parental and school alienation were seen to be almost three times more likely to report having attempted suicide than those with the lowest level. |

Suicide risk factors:

After assessing the data collected, some suicide risk factors appear to overlap between the various Arab countries. A history of anxiety and depression, low socioeconomic status, family issues in the home (broken families), a stressful youth, and bullying appear to be recurrent risk factors for suicidality. Overall stress in a child’s or adolescents’ life, bullying, depression, and social/familial estrangement/isolation are also risk factors for suicide attempts. One study identified one’s circle of friends may act as a potential risk factor for increased suicidality, particularly when a friend partakes in and discloses self-harming behaviors or disclosing depressive symptoms, with the disclosure of self-harming behaviors having a worse and stronger impact on suicidality. Female specific risk factors reported include a recent increase in alcohol consumption or recent worsening in mental health symptoms, a childhood history of recurrent exposure to stressful events, having separated parents, or not being enrolled in school. No reported male-specific risk factors. (See Table 3).

Suicide protective factors:

A high socioeconomic status, familial and peer cohesion, functional family home, and coping strategies were reported to be protective against experiencing suicidality. Religious belief was found to be protective against suicide attempts and suicidality. (See Table 4).

Table 4. Quantitative Studies Suicide Protective Factors

| Author/Date | Location | Sample | Methodology | Protective Factor |

| Baroud E., et al. (2019) | Lebanon | Adolescents | Secondary Analysis of Survey Design | Higher socioeconomic status was shown to be a protective factor against suicide in our study. |

| Din, N. C., et al. (2018) | Maylasia | Youth 13-19 | Cross-sectional Survey | Adolescents tended to have less suicidal thoughts as they had more reasons for living, greater fear of suicide, higher survival and coping beliefs, stronger moral objections, feel more responsibility towards family and friends, and with better self-acceptance. The reasons for living and general coping strategies are important protective factors to guard against suicidal ideation. |

| Dardas L. A., et al. (2020) | Jordan | Youth 14-17 | Descriptive Qualitative Design |

|

| Yuksek D. (2021) | Turkey | Highschool students, 9-10 grade. | Survey | Religiosity (b = -0.124; p < .001) was negatively correlated with suicide attempts. |

Discussion

This systematic review has provided insight into the most recent state of suicide literature in youth residing in Muslim and Arab countries. Suicide has progressively become a global lead in causes of death, ranking the fourth leading cause of death among youth aged 15-19 world-wide1. This data is in keeping with reported attempted suicide rate data dating back to the 2000s, which found that 82.9% of Muslim and Arab youths who attempted suicide were in the age range of 15- to 17-year-old. This highlights the longevity of the suicide epidemic in youth worldwide. Thus, understanding the rates of suicidality in youth and any culturally specific risk and protective factors are important in the context of treatment management of suicidality and suicide prevention.

The original goal of this study was to find suicide prevalence rates in children and youth in Muslim and Arab countries, however most studies reported rates for older youth and young adults. Thus, one main consensus stemming from this study is the need for more in-depth analyses of suicide rates in younger populations, as well as the probable need for an improvement in the reporting process for completed suicide and attempted suicide in children in Muslim and Arab countries.

In regard to the quality of the literature search, we found 25 (39%) of the articles which underwent full text review were excluded due to not reporting suicide data in our youth demographic or not making it possible to discern the data for youth only, and 17 (26%) of studies which talked about suicidality in Muslim and Arab countries did not report rates of suicide, suicide attempts, risk factors for suicide or protective factors against suicide in youth and children. This further emphasizes the need for more youth-focused suicide prevalence data for the purposes of treatment and management. Furthermore, there is an evident lack of diversity in the literature for reporting differences in suicide rates across youth and adult populations, with studies typically meshing in the rates together despite well documented differences in the literature between treatment management between these two populations, and the alarming rates of suicide as a cause of death in youth. This also means future studies should better characterize a more accurate mortality rate of Muslim and Arab youth in suicide cases, as well as in attempted suicide cases.

Across our review, there was very limited suicide attempt data in youth, with none of these studies discerning male/female rates. Attempted suicide rates in youth based in Muslim and Arab countries ranged from 4.3% to 30%. The largest attempt rate of 30% was gathered from the study that had the largest sample size when compared to the other included research studies, suggesting that this may be a more accurate estimate. were only 5 (35.7%) studies reporting an overall prevalence rate in youth. Of suicide cases reviewed in these studies, the overall suicide mortality prevalence rate for youth ranged from 0.5% to 8.9%. Similarly, very few studies examined gender differences in these rates. Of the available reported data, youth males were more likely to take their life with a suicide attempt as opposed to youth females, particularly with noticeable rate differences as male youth approached 19 in comparison to female youth.

The most prevalent youth risk factors identified for suicide attempts included anxiety, depression, stress, being abused or bullied, family issues at home, smoking, low socioeconomic status, self-guilt and shame, and loneliness/isolation. Limited differentiation in these risk factors for suicidality could be made across gender based on author reporting of data. One’s circle of friends also was also generally reported to have an impact on risk of experiencing suicidality. Particularly, youth reporting self-harming behaviours to their friends was associated with a greater risk of suicidality experienced by those friends, in comparison to youth who just reported feelings of depression. This raises some interesting risks associated with peer-based social network coping strategies. Often a strong peer social circle is protective against worsening depression, however worsening depression with a suicidality element seems to have a more negative effect on peers, particularly when self-harm is involved. Higher socioeconomic status, higher levels of satisfaction with their own social life as well as a sense of belonging and social cohesiveness either with family or friends, things to look forward to, coping strategies, strong family home, and religious beliefs were all found to be the most prevalent and consistent protective factors against suicide attempts in youth Muslims and Arabs. Many of these factors, unsurprisingly, are inversely correlated to general prevalent youth risk factors for suicide attempts. No gender-specific protective factors were reported.

Limitations: Given that this study does not utilize quantitative analyses, we are unable to ascertain whether any reported differing rates found across studies are significant, posing as a limitation in our study. Methodologies across studies also differ, as well as sampled populations – some studies sampled from clinical populations, while other sampled from community populations. Thus, the consistency in rates and factors reported may vary from clinical and community populations. A large, yet significant limitation, is the way in which prevalence rates were reported. Some of the rates were the youth proportion extrapolated from a combined youth and adult sample, and thus the rates reported in this study may not accurately represent those rates of suicidality and attempts across Muslim and Arab youth. Lastly, given suicide data is knowingly under reported, we cannot assume the suicide data accurately reflects a true range.

Future Research: The results of this systematic review have shed light on many areas within this literature that are lacking, such as identifying risk factors for attempting suicide, when the WHO identify previous suicide attempts as one of the most important risk factors for completing suicide in the general population. Looking beyond this general consensus risk factor, our research highlights the importance of identifying additional culture specific risk factors that would further indicate a greater likelihood of future completed suicide, and related, cultural-specific protective factors against suicide in youth, and differentiated by gender. In addressing this, futures studies should look to perform cultural comparative studies using this body of work with other cultural reviews on suicidality in youth and young adults to paint a broad picture on how culture and differences across cultures may affect protective factors against and risk factors for suicide in youth and young adults and any differences across gender, which could serve as useful for treatment management and prevention plans for suicidal ideation and previous attempts in youth in culturally diverse continents such as North America. This suggestion is further emphasized in importance as the WHO calls for multisectoral and interdisciplinary comprehensive requirements for effective suicide prevention strategies worldwide to be needed to help combat the current epidemic of suicide as a serious public health problem1. Future research should also focus on distinguishing gender differences on suicide (attempts and completed suicide) prevalence rates. As a result of this review, the true extent of completed suicide over the past two decades within Muslim and Arab youth is not clear, making it difficult to trend how the true rate of attempted and completed suicide may have changed over the course of the last two decades in predominant Muslim and Arab countries. Thus, future research should also aim to focus specifically on reporting mortality rates, potentially as a ratio to the total number of reported attempted cases of suicide and completed suicide cases in youth, to gauge an estimate of mortality rates associated with attempted suicide in Muslim and Arab youth.

Acknowledgments

Susan Bottiglia, information specialist who ran the search strategy across literature databases and collected the articles for review.

References

- World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates.

- Patton, G. C., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S. M., Viner, R. M., Haller, D. M., Bose, K., ... & Mathers, C. D. (2009). Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. The lancet, 374(9693), 881-892.

- Forray, A., & Yonkers, K. A. (2021). The collision of mental health, substance use disorder, and suicide. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 137(6), 1083-1090.

- Lew, B., Lester, D., Kõlves, K., Yip, P. S., Chen, Y. Y., Chen, W. S., ... & Ibrahim, N. (2022). An analysis of age-standardized suicide rates in Muslim-majority countries in 2000-2019. BMC public health, 22(1), 882.

- Arafat, S. Y., Khan, M. M., Menon, V., Ali, S. A. E. Z., Rezaeian, M., & Shoib, S. (2021). Psychological autopsy study and risk factors for suicide in Muslim countries. Health science reports, 4(4), e414.

- Dardas, L. A. (2021). Depression and suicide among Arab adolescents: 7 messages from research in Jordan. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing.

- Pritchard, C., Iqbal, W., & Dray, R. (2020). Undetermined and accidental mortality rates as possible sources of underreported suicides: population-based study comparing Islamic countries and traditionally religious Western countries. BJPsych open, 6(4), e56.

- Pritchard, C., & Amanullah, S. (2007). An analysis of suicide and undetermined deaths in 17 predominantly Islamic countries contrasted with the UK. Psychological medicine, 37(3), 421-430.

- Brunstein Klomek, A., Nakash, O., Goldberger, N., Haklai, Z., Geraisy, N., Yatzkar, U., ... & Levav, I. (2016). Completed suicide and suicide attempts in the Arab population in Israel. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(6), 869-876.

- Orri, M., Vergunst, F., Turecki, G., Galera, C., Latimer, E., Bouchard, S., ... & Côté, S. M. (2022). Long-term economic and social outcomes of youth suicide attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 220(2), 79-85.

- Amini, S., Bagheri, P., Moradinazar, M., Basiri, M., Alimehr, M., & Ramazani, Y. (2021). Epidemiological status of suicide in the Middle East and North Africa countries (MENA) from 1990 to 2017. Clinical epidemiology and global health, 9, 299-303.

- Sheikholeslami, H., Kani, C., & Ziaee, A. (2008). Attempted suicide among Iranian population. Suicide and life-threatening behavior, 38(4), 456-466.

- Arafat, S. Y., Baminiwatta, A., Menon, V., Singh, R., Varadharajan, N., Guhathakurta, S., ... & Rezaeian, M. (2023). Prevalence of suicidal behaviour among students living in Muslim-majority countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych open, 9(3), e67.

- Al Madni, O. M., Kharoshah, M. A. A., Zaki, M. K., & Ghaleb, S. S. (2010). Hanging deaths in Dammam, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of forensic and legal medicine, 17(5), 265-268.

- Azmak, A. D. (2006). Suicides in Trakya region, Turkey, from 1984 to 2004. Medicine, science and the law, 46(1), 19-30.

- Dervic, K., Amiri, L., Niederkrotenthaler, T., Yousef, S., Salem, M. O., Voracek, M., & Sonneck, G. (2012). Suicide rates in the national and expatriate population in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(6), 652-656.

- Koronfel, A. A. (2002). Suicide in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine, 9(1), 5-11.

- Snowdon, J. (2020). Suicide and ‘hidden suicide’: a comparison of rates in selected countries. Australasian psychiatry, 28(4), 378-382.

- Baroud, E., Ghandour, L. A., Alrojolah, L., Zeinoun, P., & Maalouf, F. T. (2019). Suicidality among Lebanese adolescents: prevalence, predictors and service utilization. Psychiatry research, 275, 338-344.

- Ibrahim, H., & Mahfoud, Z. R. (2021). No association between suicidality and weight among school-attending adolescents in the United Arab Emirates. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 618678.

- Mirza, S., Rehman, A., Haque, J., & Khan, M. M. (2024). Perceptions of suicide among Pakistanis: results of an online survey. Archives of suicide research, 1-18.

- Siddik, M. A. B., Manjur, M., Pervin, I., Khan, M. B. U., & Sikder, C. (2024). Suicide attempts and depression associated factors among the male child sexual abuse survivors in Bangladesh. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 16, 100736.

- Vally, Z., & Helmy, M. (2023). The prevalence of suicidal behaviour and its associated risk factors among school-going adolescents resident in the United Arab Emirates. Scientific reports, 13(1), 19937.

- Sawalha, A. F., O'Malley, G. F., & Sweileh, W. M. (2012). Pesticide poisoning in Palestine: a retrospective analysis of calls received by poison control and drug information center from 2006–2010. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine, 24(3), 171-177.

- Copeland, M., Alqahtani, R. T., Moody, J., Curdy, B., Alghamdi, M., & Alqurashi, F. (2021). When friends bring you down: peer stress proliferation and suicidality. Archives of suicide research, 25(3), 672-689.

- Dardas, L. A., Price, M. M., Arscott, J., Shahrour, G., & Convoy, S. (2021). Voicing Jordanian adolescents’ suicide. Nursing research, 70(1), E1-E10.

- Dehnel, R., Dalky, H., Sudarsan, S., & Al-Delaimy, W. K. (2024). Suicidality among syrian refugee children in Jordan. Community mental health journal, 60(2), 224-232.

- Yıldız, M., Orak, U., Walker, M. H., & Solakoglu, O. (2019). Suicide contagion, gender, and suicide attempts among adolescents. Death studies.

- Yüksek, D. A. (2021). Durkheim’s theory of suicide: A study of adolescents in Turkey. İstanbul University Journal of Sociology, 41(1), 7-25.

- Din, N. C., Ibrahim, N., Amit, N., Kadir, N. B. Y. A., & Halim, M. R. T. A. (2018). Reasons for living and coping with suicidal ideation among adolescents in Malaysia. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences: MJMS, 25(5), 140.