Archive : Article / Volume 2, Issue 1

- Case Report | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-2330/014

Isolated Acute Rheumatic Pancreatitis- A Case Report

Morning Star hospital, Marthandam, Kanyakumari District, India

Ramachandran Muthiah

Ramachandran Muthiah, (2023). Isolated Acute Rheumatic Pancreatitis- A Case Report. Journal of Clinical and Medical Reviews. 2(1). DOI: 10.58489/2836-2330/014

© 2023 Ramachandran Muthiah, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 14-12-2022

- Accepted Date: 23-12-2022

- Published Date: 06-03-2023

Acute abdomen, pancreatitis, ASO titer, elevated pancreatic enzymes, antibiotics.

Abstract

Aim: To emphasize the role of antibiotics in acute pancreatitis as prophylactic and therapeutic benefits. Case Report: A 32-year-old obese male was admitted with acute abdomen in the emergency room. He was supported with intravenous fluids and the blood chemistry revealed elevated amylase and lipase levels, raised ESR and a positive ASO titer test. CT abdomen suggested interstitial edematous pancreatitis (IEP) and no fluid collection. Patient was treated with IV cefotaxime and metronidaziole and his condition remarkably improved with therapy and blood parameters returned normal at the end of 4 weeks and follow up CT revealed no abnormal findings and symptom free thereafter. Conclusion: Acute pancreatitis is usually a sterile inflammatory process caused by chemical autodigestion of pancreas. The edematous form of acute pancreatitis needs to correct its etiological factor to avoid recurrence. It is observed as an initial manifestation of group A beta hemolytic streptococcal infection in this patient and antibiotics play a role as curative and prophylactic in selected cases.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a condition where the pancreas becomes inflammed (swollen) over a short period of time. Most people with acute pancreatitis start to feel better within about a week and have no further problems. It is sometimes associated with a systemic inflammatory response that can impair the functions of other organs, can go on to develop serious complications. Thus, there is a wide spectrum of disease from mild (80%), where patients recover within a few days, to severe (20%) with prolonged hospital stay, the need for critical care support, and 15-20% risk of death if patients have organ failure during the first few weeks of illness [1].

It occurs with an estimated incidence of 10-40 per 100,000 per year in the UK [2]. An increase in the annual incidence for acute pancreatitis has been observed worldwide varies between 4.9 and 73.4 cases per 100,000 [3],[4]. Every year, there are 275,000 hospitalisations for acute pancreatitis in the United States. In 2009, it is the most common gastroenterology discharge diagnosis with a cost of 2.6 billion dollars.

The evolving issues of antibiotics, nutrition, endoscopic, radiologic, surgical and other minimally invasive interventions will be addressed on early management to decrease morbidity and mortality.

Some studies have suggested that the administration of prophylactic antibiotics reduces the risk of pancreatic necrosis becoming infected [5]. Abdominal pain is the presenting manifestation of acute rheumatic fever [6], usually precedes the other rheumatic signs and it is the consequence of rheumatic inflammatory process affecting the pancreas in this patient and so this case had been reported.

Case Report

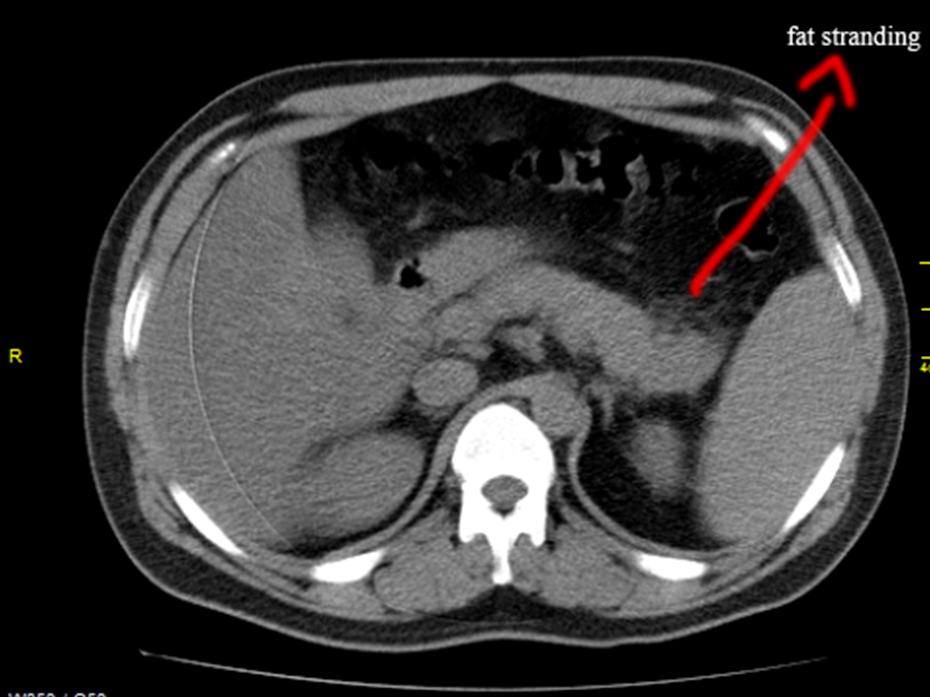

A 32 years old male was admitted with sudden onset of severe abdominal pain and he was found to be toxic and emaciated. His pulse rate was 114 bpm, blood pressure 90/60 mmHg and temperature 100.4∙F. Physical examination revealed distended abdomen with tenderness in the epigastric region. He had a history of alcoholic drinks occasionally. He was on anticonvulsants (phenytoin sodium 100mg twice daily) for the past 4 years as he suffered 2 to 3 episodes of seizure attacks before and his CT brain revealed normal earlier. On admission, his serum amylase was 548 IU/L (normal 10 to 96 IU/L). The total leukocyte counts 7190 cells/cumm blood (normal 4000 to 10000/cumm of blood), neutrophils 65.8% (normal 40 to 75%), lymphocytes 26.3% (normal 25 to 35%), monocytes 4% (normal 3.5 to 11.5%), eosinophils 3.5% (normal 2 to 6%), basophils 0.4% (normal 0 to 1%). ESR (Erythrocyte sedimentation rate) 26 mm in one hour (normal 0 to 14 mm per hour). Serum bilirubin (total) 1.2mg/dl (normal 0.4 to 1.2mg/dl). Random blood glucose 98mg/dl (normal 60 to 125 mg/dl). Total cholesterol 180mg/dl (normal 150 to 220 mg/dl), serum triglycerides 270mg/dl (normal 50 to 150 mg/dl). Serum SGOT (AST) 88 IU/L (normal 5 to 41 IU/L, SGPT (ALT) 78 IU/L (normal 5 to 50 IU/L). The renal parameters and serum electrolytes were within normal range. Serum lipase was highly raised as 1476 IU/L (normal < 60>Figures 1 and 2, with normal pancreatic parenchyma and no significant ductal dilatation and calcification. The liver and gallbladder appear normal, no evidence of gallstones and no fluid collections. The abdominal distension subsided on 4th day and the patient was advised to resume semisolid liquid diet, tendor coconut water, fruits and smashed vegetables without chillies slowly. The milk products were avoided. His condition began to improve thereafter. After one week of treatment, the amylase level decreased to 303.1 IU/L and lipase level becoming 240.4 IU/L, AST 84 IU/L, ALT 80 IU/L. Then one week thereafter, the amylase level reduced to 151.2 IU/L, lipase level 128.4 IU/L, AST 49 IU/L and ALT remaining high as 89 IU/L. At 3rd week, AST 36 IU/L, ALT 51 IU/L, amylase 148 IU/L, lipase 115 IU/L and ASO titer 288.5 IU/ml.

The treatment continued and at the end of 4 weeks, the amylase 69 IU/L, lipase 31 IU/L and ASO titer became negative. The CT abdomen revealed no fat stranding and the pancreas appeared normal. The patient get discharged to home and advised to avoid alcohol and fatty foods thereafter. The patient was symptom free and healthy on one year follow up, advised lifelong penicillin prophylaxis with oral penicillin V 250mg twice daily to prevent recurrent attacks of pancreatitis. Since he is obese with body mass index (BMI 32%), regular exercise programmes and diet control were advised for weight reduction with periodic medical check-up.

The RT PCR for COVID 19 infection (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test) was negative at present and it was not done initially since unknown at the time of presentation.

Discussion

Etiopathogenesis

The pancreas is a secretory organ with both endocrine and exocrine functions and the main functional unit is the acinar cell, which comprises the parenchyma of the gland. Exocrine products from the acinar cells are secreted into a tubular system and the digestive enzymes are released via the pancreatic duct into the small intestine where they are activated to break down the fats and proteins. The digestive hormones (insulin & glucagon) produced by the pancreas are released into the blood stream where they help to regulate the blood glucose level.

Normally, digestive enzymes released by the pancreas are not activated to break down fats and proteins until they reach the small intestine. Trypsin is a digestive enzyme produced in the pancreas in an inactive form and ethanol molecules affect the pancreatic cells, triggering them to activate trypsin prematurely. When the digestive enzymes are activated in the pancreas, inflammation and local damage as ‘acinar cell destruction’ histologically occurs, leading to pancreatitis. Neutrophil polymorphs and macrophages infiltrate the pancreas and release their own proteases, free radicals, and cytokines which compound the vicious cycle of tissue damage and inflammation, inducing an ‘acute systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)’ and organ damage. The patient may become dehydrated and then heart, lungs, kidney fail. In very severe cases, pancreatitis can result in bleeding into the gland, leading to shock, serious tissue damage, infection, fluid collections and sometimes death.

There are many causes of pancreatitis as obstruction of the secretory tree or direct parenchymal cell damage. The gallstones, infection and alcoholism are the most common causes of acute pancreatitis. In recurrent acute pancreatitis, Oddi sphincter manometry is performed and a basal sphincteric pressure > 40 mmHg [7] is the most common abnormal finding described in 30-40% of cases. DIP (drug induced pancreatitis), which is an overlooked diagnosis in the clinical setting, must be rigorously considered whenever patients are on a set of new drugs and presenting with even, minimal symptoms and signs of acute pancreatitis.

Drugs are responsible for 0.1% - 2% of acute pancreatitis incidents. The majority of drug-induced pancreatitis cases are mild to moderate in severity; however, severe and even fatal cases can occur.The newly emerged drugs like propofol infusion, antidiabetics (GLP1- Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor) agonists and DDP4 (Dipeptidyl Peptase IV) inhibitors and SGLT2 (Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2) inhibitors, particularly, canagliflozin), antibiotics (minocycline), antihypertensive agents (enalapril, lisinopril, captopril, ramipril, perindopril, and less frequently angiotensin receptor blockers), proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, pantoprazole, and lansoprazole), anticancer drugs (nivolumab, pembrolizumab, ipilimumab), the newer TKIs (Tyrosine kinase inhibitors- vemurafenib and ponatinib), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib), and non-selective TACE (Transarterial chemoembolization), and direct-acting antiviral therapies (DAAs) of hepatitis C virus along with ribavirin and currently, more than 500 drugs have been reported in the World Health Organization database as offenders of acute pancreatitis. The onset of drug-induced pancreatitis after initiation of medications ranges from a few months to several years, with a median of 5 weeks; onset after rechallenge can occur within hours. The latency between initiation of the offending drug and developing acute pancreatitis can be short (less than 24 h), intermediate (1-30 days), and long (more than 30 days). According to Badalov classification system of drug induced pancreatitis, the latency is described as consistent with the drug-related pancreatitis when 75% of cases were related to any of the previously mentioned groups. Potential mechanisms for drug-induced acute pancreatitis include pancreatic duct constriction, immune-mediated inflammatory response, direct cellular toxicity, arteriolar thrombosis, metabolic effects, hypersensitivity (Idiosyncratic) reactions, localized angioedema effect in the pancreas and Influence of medication on the bile flow.

Infections can result from a variety of sources

- Bacterial translocation- from small bowel and colon through transmural colonic migration is a major source of infection in necrotizing pancreatitis [10]. Endotoxemia resulting from the release of components of gram-negative bacteria from the gut is common in patients with acute pancreatitis. The bacterial translocation from the gut lumen to mesenteric lymph nodes and subsequent hematogenous dissemination could be a possible mechanism of the development of pancreatitis. Impaired body defences predispose to translocation of gastrointestinal organisms and toxins with subsequent secondary bacterial infection.

- Hematogenous spread

- Biliary sources- bile duct stone or gall bladder infection ascending from duodenum via the main pancreatic duct can lead to infected pancreatic necrosis.

Table 1. Infectious agents causing pancreatitis

Varicella-zoster virus Leptospirosis

Cytomegalo virus (CMV) legionella (L. pneomophila Covid 19 virus found in plumbing, Shower

|

Table 2 showing the Bedside index of severity of acute pancreatitis (BISAP) [35].

Blood urea nitrogen level > 25mg/dl (89 mmol/l)

Impaired mental status (Glasgow coma score < 15>

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

|

Table 3 showing the criteria of SIRS (systemic inflammatory response syndrome) [36]

CT (Computed Tomography) Imaging

MR (Magnetic Resonance) Imaging

ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography)

MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography)

Secretin Stimulated MRCP (sMRCP)

Insulin infusion (0.1 units/kg/hour in 24 hours until triglyceride level became < 500>

Outcome

The disease takes a mild course in most patients and the severe form carries a hospital mortality rate of 15%. Infection occurs in 20-40% of cases, contribute to 80% of deaths in acute pancreatitis [78] and it is associated with worsening organ dysfunction in < 5>

Case analysis

This 32 years old male was presented with acute abdomen as an initial manifestation of rheumatic fever due to Lancifield group A beta hemolytic streptococci [82] as evidenced by raised ASO titer and ESR. Elevated amylase and lipase with CT features of peripancreatic inflammatory changes as ‘mistiness’ (fat strandings) suggesting acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis (IEP) as in Figures 1 & 2 and these inflammatory changes are responded to antibiotic therapy. The patient improved dramatically within few days and resumed oral intake without any further complications. Cefotaxime showed good penetration into the pancreas to eradicate the infective process [83].

Presence of obesity, history of alcoholism, use of anticonvulsants and moderately raised triglyceride levels are the risk factors to trigger the pancreatic infection by streptococcus in this case. Periarteriolar connective tissue inflammation caused by the organism causes vasculitis and the resultant ischemia in the pancreas as an isolated event, may predisposes to further infection and so penicillin prophylaxis is indicated.

Preventive measures

a) A healthy lifestyle can reduce the chances of developing acute pancreatitis.

Hypertriglyceridemia causes 2 to 5 % of cases of pancreatitis and is associated with inherited disorders of lipoprotein metabolism, congenital type1, II and V without a precipitating factor in children [84]. Chylomicrons are triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles believed to be responsible for pancreatic inflammation. They usually present in the circulation when serum triglyceride levels exceed 10 mmol/L. These largest of lipoproteins might impair circulatory flow in capillary beds; if this occurs in the pancreas, the resulting ischemia might disturb the acinar structure and expose these triglyceride-rich particles to pancreatic lipase. The pro-inflammatory non-esterified free fatty acids generated from the enzymatic degradation of chylomicron-triglycerides (ie, the release of free fatty acids by lipase) may lead to further damage of pancreatic acinar cells and microvasculature. Subsequent amplification of the release of inflammatory mediators and free radicals may ultimately lead to necrosis, edema, and inflammation. Hypertriglyceridemia was the cause of 56 GAS pharngitis and invasive infections are more common as seasonal trends, “a wave of airborne infection” with close ‘person-to-person contacts’ and predisposing to viral infections [113]. Mucosal hygiene (nasal, oral cavity and genitals) is an important measure to prevent it [114]. COVID 19 is similarly presenting and amenable to antibiotics in mild cases and vaccine development remains as a challenge for both conditions since seroconversions occurring frequently as noticed in the United Kingdom due to new outbreaks of corona virus with different strains recently. Live attenuated vaccine similar to oral polio vaccine as “drops” at the exposed mucosal surfaces of the body (mucosal vaccine) to induce immunity (both ‘humoral’ or serum immunity and local immune response) is a better option to control the outbreaks. Acute abdomen, as pancreatitis and acute lung damage, as ARDS are the presenting manifestations of both of these infections. Penicillin prophylaxis is indicated in endemic areas to prevent it’s unexpected outbreaks and, serum ASO titer screening and PCR tests are advised to identify these infections.Conclusion

References

- Johnson, C.D., Besselink, M., G.,Carter,R.(2014) Acute Pancreatitis, British Medical Journal, 349, g 4859.

- Goldacre, M.,J., Roberts, S.,E.,(2004) Hospital Admission For Acute Pancreatitis In An English Population, 1963-1998: Database Study of Incidence And Mortality, British Medical Journal, 328, 1466-1469.

- Rebours, V., Vullierma, M.,P., Hentic, O., et al (2012) Smoking And The Course of Recurrent Acute And Chronic Alcoholic Pancreatitis: A Dose Dependent Relationship. Pancreas, 41, 1219-1224.

- Whitcomb, D.,C. (2005) Genetic Polymorphisms In Alcoholic Pancreatitis, Digestive Diseases, 23, 247-254.

- Isenmann,R.,Runzi, M., Kron,M., et al (2004) Prophylactic Antibiotic Treatment In Patients With Predicted Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Placebo- Controlled, Double-Blind Trial, Gastroenterology, 126, 997-1004.

- Picard,E.,Gedalia,A.,Benmeir,P.,Zucker, N.,Barki,Y.,(1992) Abdominal Pain With Free Peritoneal Fluid Detected By Ultrasonography As A Presenting Manifestation of Acute Rheumatic Fever, Annals of The Rheumatic Diseases, 51, 394-395.

- Hogan,W.,J.,Geenen,J.,E.,Dodds,W.,J.(1987)Dysmotility Disturbances of The Biliary Tract: Classification, Diagnosis, And Treatment, Seminars in Liver Disease, 7, 302-310.

- Beger,H.,G., Rau, B.,M.(2007) Severe Acute Pancreatitis: Clinical Course And Management, World Journal of Gastroenterology, 13, 5043-5051.

- Perez, A., Whang, E.,E., Brooks, D.,C., et al (2002). Is Severity of Necrotizing Pancreatitis Increased In Extended Necrosis And Infected Necrosis? Pancreas, 25, 229–233.

- Mourad, M.,M., Evans, R.,P.,T., Kalidindi, V., Navaratnam, R., Dvorkin, L., Bramhall, S.,R..(2017) Prophylactic Antibiotics In Acute Pancreatitis: Endless Debate. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 99, 107–112.

- Reuken, P.,A., Albig, H., Rödel, J., Hocke, M., Will, U., Stallmach, A., et al (2018). Fungal Infections In Patients With Infected Pancreatic Necrosis And Pseudocysts: Risk Factors And Outcome. Pancreas, 47, 92–98.

- Chiu,C.,H., Lin,T.,Y., Wu.J.,L. (1996) Acute Pancreatitis Associated With Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 22, 724-726.

- Liu,F.,Long,X.,Zhang,B.,Chen,X.,Zhang,Z., (2020) ACE2 Expression In Pancreas May Cause Pancreatic Damage After SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Clinical Gastroeterology And Hepatology, 18, 2128-2130.

- Wang, F.,Wang,H.,Fan,J.,(2020)Pancreatic Injury Patterns In Patients With Corona virus Disease 19 Pneumonia, Gastroenterology, 159, 367-370..

- Aloysius,M.,M., Thatti,A., Gupta, A., Sharma,N., Bansai,P.,Goyal.H., (2020) COVID 19 Presenting As Acute Pancreatitis, Pancreatology, 20, 1026-1027.

- Anand, E.,R.,Major,C.,Pickering,O.,Nelson,M.(2020) Acute Pancreatitis In A COVID 19 Patient, British Journal of Surgery, 107, e182.

- Kandasamy,S., (2020) An Unusual Presentation of COVID 19: Acute Pancreatitis, Annals of Hepato-biliary- Pancreatic Surgery, 24, 539-541.

- Bradley 3rd, E.,L.,(1993) A Clinically Based Classification System For Acute Pancreatitis. Summary of The International Symposium On Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 Through 13, 1992. Archives of Surgery, 128, 586–590.

- Besselink ,M.,G., Van Santvoort, H.,C., Witteman, B.,J., Gooszen, H.,G., (2007) Management of Severe Acute Pancreatitis: It’s All About Timing. Current Opinion In Critical Care , 13, 200–206.

- Johnson, C.,D., Abu-Hilal, M.,(2004) Persistent Organ Failure During The First Week As a Marker of Fatal Outcome In Acute Pancreatitis. Gut, 53, 1340–1344.

- Abu-Zidan, F.,M., Bonham, M.,J., Windsor, J.,A..(2000) Severity of Acute Pancreatitis: A Multivariate Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers And Modified Glasgow Criteria. British Journal of Surgery, 87, 1019–1023.

- Toouli ,J., Brooke-Smith, M., Bassi, C., Carr-Locke, D., Telford, J., Freeny, P., et al.(2002) Guidelines For The Management Of Acute Pancreatitis. Journal of Gastroenterology And Hepatology, February:17(Suppl), S15–39.

- Tenner, S., Baillie, J., DeWitt, J., Vege, S.,S..(2013) Management of Acute Pancreatitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108, 1400–1416.

- Rompianesi, G., Hann, A., Komolafe, O., Pereira, S.,P., Davidson, B.,R., Gurusamy, K.,S..(2017) Serum amylase and lipase and urinary trypsinogen and amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD012010.

- Matull,W.,R., Pereira, S.,P., O’Donohue,J.,W.(2006) Biochemical Markers of Acute Pancreatitis, Journal of Clinical Pathology, 59, 340-344.

- Chang, K., Lu, W., Zhang, K., Jia, S., Li, F., Wang, F., et al (2012) Rapid Urinary Trypsinogen 2 Test In The Early Diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis: A Meta-Analysis. Clinical Biochemistry, 45, 1051–1056.

- Staubli,S., M., Oertli, D., Nebiker, C.,A..(2015) Laboratory markers predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. Critical Reviews In Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 52, 273–283.

- Kibar, Y.,I., Albayrak, F., Arabul, M., Dursun, H., Albayrak, Y., Ozturk, Y..(2016) Resistin: New Serum Marker For Predicting Severity Of Acute Pancreatitis. Journal of International Medical Research. 44, 328–337.

- Yu, P., Wang, S., Qiu, Z., Bai, B., Zhao, Z., Hao, Y., et al.(2016) Efficacy Of Resistin And Leptin In Predicting Persistent Organ Failure In Patients With Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreatology, 16, 952–957.

- Assicot, M., Gendrel, D., Carsin, H., et al.(1993) High Serum Procalcitonin Concentrations In Patients With Sepsis And Infection. Lancet. 341, 515–518.

- Yang, C.,J., Chen, J., Phillips, A.,R.,J., Windsor, J.,A., Petrov, M.,S.(2014). Predictors Of Severe And Critical Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review. Digestive And Liver Disease.46, 446–451.

- Chang, L., Lo, S.R., Stabile, B.E., et al. (1998) Gallstone Pancreatitis: A Prospective Study on the Incidence of Cholangitis and Clinical Predictors of Retained Common Bile Duct Stones. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 93, 527-531.

- Cho, J.,H., Kim, T.,N., Chung, H.,H., Kim, K.,H..(2015) Comparison Of Scoring Systems In Predicting The Severity Of Acute Pancreatitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 21, 2387–2394.

- Wu, B.,U., Johannes, R.,S., Sun, X., Tabak, Y.,Conwell, D.,L.,Banks, P.,A..(2008)The Early Prediction Of Mortality In Acute Pancreatitis: A Large Population Based Study. Gut, 57, 1698-1703.

- Park, J.,Y., Jeon, T.,J., Ha, T.,H., Hwang, J.,T., Sinn, D.,H., Oh, T.,H., et al.(2013) Bedside Index For Severity In Acute Pancreatitis: Comparison With Other Scoring Systems In Predicting Severity And Organ Failure. Hepatobiliary And Pancreatic Diseases International. 12, 645–650.

- Todd Baron, (2013) Managing Severe Acute Pancreatitis,Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 80, 354-359.

- Chakraborty, R.,K., Burns, B.(2020) Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, Last update, November 16.

- Kim, Y.,K., Ko, S.,W., Kim, C.,S., Hwang, S.,B..(2006) Effectiveness of MR Imaging For Diagnosing The Mild Forms of Acute Pancreatitis: Comparison With MDCT. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 24, 1342–1349.

- Balthazar, E.,J., Robinson, D.,L., Megibow, A.,J., Ranson, J.,H.. (1990) Acute Pancreatitis: Value of CT In Establishing Prognosis. Radiology, 174, 331–336.

- Bollen, T.,L., Singh, V.,K., Maurer, R., et al (2011). Comparative Evaluation of The Modified CT Severity Index And CT Severity Index In Assessing Severity of Acute Pancreatitis. AJR (American Journal of Roentgenology), 197, 386–392.

- Balthazar, E.,J.,(2002). Acute Pancreatitis: Assessment of Severity With Clinical And CT Evaluation , Radiology, 223, 603–613.

- Giljaca,V.,Gurusamy,K.,S.,Takwoingi,Y.,Higgie,D.,Poropat,G.,Stimac,D.,et. al (2015) Endoscopic Ultrasound Versus Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography For Common Bile Duct Stones, Cochrane Data Base Systematic Reviews, 2, CD011549.

- Sharma,M.,Pathak,A.,RameshBabu,C.,S.,Rai,P.,Kirnake,V.,Shoukat,A.,(2016) Imaging of Pancreas Divisum By Linear - Array Endoscopic Ultrasonography, Endoscopic Ultrasound, 5, 21-29.

- Byme,M.,F.,Jowell,P.,S.,(2002)Gastrointestinal Imaging: Endoscopic Ultrasound, Gastroenterology, 122, 1631-1648.

- Xiao,B.,Zhang,X.,M.,Tang,W.,Zeng,N.,L.,Zhai,Z.,H.,(2010)Magnetic Resonance Imaging For Local Complications of Acute Pancreatitis: A Pictorial Review, World Journal of Gastroenterology, 16, 2735-2742.

- Tse, F., Yuan, Y.,(2012) Early Routine Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Strategy Versus Early Conservative Management Strategy In Acute Gallstone Pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews,16, CD009779.

- Hurter,D.,DeVries,C.,Potgieter,P.,Barry,R.,Botha,F.,Joubert,G.,(2008) Accuracy of MRCP Compared to ERCP In The Diagnosis of Bile Duct Disorders, South African Journal of Radiology, 12, a 580.

- Yattoo, G.,N., Waiz, G.,A., Feroze, A.,S., Showkat, Z., Gul, J.,(2014) The Efficacy of Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography In Assessing The Etiology of Acute Idiopathic Pancreatitis. International Journal of Hepatobiliary And Pancreatic Diseases. 4, 32-39.

- Manfredi,R.,Pozzi Mucelli,R.,(2016) Secretin-Enhanced MR Imaging of The Pancreas, Radiology, 279, 29-43

- Banks, P., A., Freeman, M.,L.,(2006) Practice Guidelines In Acute Pancreatitis. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 101, 2379–2400.

- Eckerwall, G.,E., Tingstedt, B.,B.,A., Bergenzaun, P.,E., et al (2007) Immediate Oral Feeding In Patients With Mild Acute Pancreatitis Is Safe And May Accelerate Recovery—A Randomized Clinical Study, Clinical Nutrition, 26, 758–763..

- Takeda, K., Mikami, Y., Fukuyama, S., et al.(2005) Pancreatic Ischemia Associated With Vasospasm In The Early Phase of Human Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis. Pancreas, 30, 40–49.

- Fisher,J.,M.,Gardner,T.,B.,(2012) The “Golden Hours “ of Management In Acute Pancreatitis, American Journal of Gastroenterology, 107, 1146-1150.

- Gardner,T.,B.,Vege,S.,S.,Pearson,R.,K.,et al (2008) Fluid Resuscitation In Acute Pancreatitis, Clinical Gastroenterology And Hepatology, 10, 1070-1076.

- Wu., B.,U., Hwang, J.,Q., Gardner, T.,H. et al (2011). Lactated Ringer's Solution Reduces Systemic Inflammation Compared With Saline In Patients With Acute Pancreatitis. Clinical Gastroenterology And Hepatology, 9, 710–717.

- Mao, E.,Q., Fei, J., Peng, Y.,B., et al (2010). Rapid Hemodilution Is Associated With Increased Sepsis And Mortality Among Patients With Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Chinese Medical Journal (English Edition),123, 1639–1644.

- De-Madaria, E., Soler-Sala, G., Sánchez-Paya, J., et al (2011) Influence of Fluid Therapy On The Prognosis of Acute Pancreatitis: A Prospective Cohort Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology,106, 1843–1850.

- Eckerwall, G., Olin, H., Andersson, B., et al (2006). Fluid Resuscitation And Nutritional Support During Severe Acute Pancreatitis In The Past: What Have We Learned And How Can We Do Better? Clinical Nutrition, 25, 497–504.

- Windsor,A.,C.,Kanwar,S.,Li,A.,G., et al (1998) Compared With Parenteral Nutrition, Enteral Feeding Attenuates The Acute Phase Response And Improves Disease Severity In Acute Pancreatitis, Gut, 42, 431-435.

- Bakker, O.,J., Van Brunschot, S., Van Santvoort, H.,C., Besselink, M.,G., Bollen, T.,L., Boermeester, M.,A., et al (2014) Early Versus On-Demand Nasoenteric Tube Feeding In Acute Pancreatitis. New England Journal of Medicine,. 371, 1983–1993.

- Eatock,F.,C.,Chong,P.,Menezes,N.,et al (2005) A Randomized Study of Early Nasogastric Versus Nasojejunal Feeding In Severe Acute Pancreatitis, American Journal of Gastroenterology, 100, 432-439.

- Pederzoli,P.,Bassi,C.,Vesentini,S.,et al (1993) A Randomized Multicenter Clinical Trial of Antibiotic Prophylaxis of Septic Complications In Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis With Imipenem, Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics, 176, 480-483.

- Jiang, K., Huang, W., Yang, X.,N., et al (2012). Present And Future of Prophylactic Antibiotics For Severe Acute Pancreatitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology., 18, 279–284.

- Schmid, S., Uhl,W.,Friess, H.,et al (1999) The Role of Infection In Acute Pancreatitis, Gut, 45, 311-316.

- De Waele, J.,J..(2011) Rational Use of Antimicrobials In Patients With Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Seminars In Respiratory And Critical Care Medicine, 32, 174–180.

- Eloubeidi, M.,A., Tamhane, A., Varadarajulu, S., et al (2006). Frequency of Major Complications After EUS-Guided FNA of Solid Pancreatic Masses: A Prospective Evaluation, Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 63, 622–629.

- Nathens, A.,B.,Curtis,J.,R.,Beale,R.,J.,et al (2004) Management of The Critically ill Patient With Severe Acute Pancreatitis, Critical Care Medicine, 32, 2524-2536.

- Buchler, M., Malfertheiner, P., et al (1992) Human Pancreatic Tissue Concentration of Bactericidal Antibiotics, Gastroenterology, 103, 1902–1908.

- Otto, W., Komorzycki, K., Krawczyk, M..(2006) Efficacy of Antibiotic Penetration Into Pancreatic Necrosis. HPB (The Official Journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association), 8, 43–48.

- Schubert, S., Dalhoff, A..(2012) Activity of Moxifloxacin, Imipenem, And Ertapenem Against Escherichia Coli, Enterobacter Cloacae, Enterococcus Faecalis, And Bacteroides Fragilis In Monocultures And Mixed Cultures In An In Vitro Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Model Simulating Concentrations In The Human Pancreas. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 56, 6434-6436.

- Li, J., Chen, T.R., Gong, H.L., Wan, M.H., Chen, G.Y. and Tang, W.F.(2012) Intensive Insulin Therapy in Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Meta Analysis and Systematic Review. West Indian Medical Journal, 61, 574-579.

- Stefanutti, C., Labbadin, G. and Morozzi, C. (2013) Severe Hypertriglyceridemia-Related Acute Pancreatitis. Therapeutic Apheresis and Dialysis, 17, 130-137.

- He, C., Zhang, L., Shi, W., et al. (2013) Coupled Plasma Filtration Adsorption Combined with Continuous Veno-Venous Hemofiltration Treatment in Patients with Severe Acute Pancreatitis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 47, 62-68.

- Pannala, R. and Chari, S.T. (2009) Corticosteroid Treatment for Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Gut, 58, 1438-1439. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2009.183293

- Dua, M.,M., Jensen, C.,W., Friedland, S., Worth, P.,J., Poultsides, G.,A., Norton, J.,A., et al (2018), Isolated Pancreatic Tail Remnants After Transgastric Necrosectomy Can Be Observed. Journal of Surgical Research,. 231, 109–115

- Bang, J.,Y., Wilcox, C.,M., Navaneethan, U., Hasan, M.,K., Peter, S., Christein, J., et al (2018), Impact of Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome On The Endoscopic Management of Pancreatic Fluid Collections. Annals of Surgery, 267, 561–568.

- Pham, X-B.,D., De Virgilio, C., Al-Khouja, L., Bermudez, M.,C., Schwed, A.,C., Kaji, A.,H., et al (2016) Routine Intraoperative Cholangiography Is Unnecessary In Patients With Mild Gallstone Pancreatitis And Normalizing Bilirubin Levels. American Journal of Surgery. 212, 1047–1053.

- Delcenserie,R.,Yzet,T.,Ducroix,J.,P.,(1996) Prophylactic antibiotics In Treatment of Severe Acute Alcoholic Pancreatitis, Pancreas, 13, 198-201.

- Mann,D.,V.,Hershman, M.,J.,Hitinger,R.,et al (1994) Multicentre Audit of Death From Acute Pancreatitis, British Journal of Surgery, 51, 890-893.

- Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines (2013). IAP/APA Evidence-Based Guidelines For The Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 4 (Suppl 2), e1–15.

- Wyncoll, D.,L.,(1999) The Management of Severe Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis: An Evidence Based Review of The Literature, Intensive Care Medicine, 25, 146-156.

- Cross, H.,D.(1965) Pancreatitis And Acute Rheumatic Fever, The Journal of The Maine Medical Association, 56 , 268.

- Lankish,P.,G., Klesel,N.,Seeger,K.,Seidel,G.,Winckler,K.(1983) Penetration of Cefotaxime Into The Pancreas, Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie , 21, 601-603.

- Murphy, M.,J.,Sheng,X., MacDonald, T.,Wei,L.,(2012) Hypertriglyceridemia And Acute Pancreatitis, Archives of Internal Medicine, 173, 1-3.

- Ramachandran (2019) Occupational Health- Mineralization of Heart Valves, 2nd Global Summit On Occupational Health & Safety, Dubai-Deira (Crowne Plaza), October, 11-12 (You Tube).

- You.Y.,et al (2018) Scarlet Fever Epidemic In China Caused By Streptococcus Pyogenes Serotype M12: Epidemiologic And Molecular Analysis, EBiomedicine, 28, 128-135.

- Tse, H. et al (2012). Molecular Characterization of The 2011 Hong Kong Scarlet Fever Outbreak. Journal of Infectious. Diseases. 206, 341–351.

- Turner, C. E. et al (2016). Scarlet Fever Upsurge In England And Molecular-Genetic Analysis In North-West London, 2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22, 1075–1078.

- Chalker, V. et al (2017). Genome Analysis Following A National Increase In Scarlet Fever In England 2014. BMC Genomics, 18, 224.

- Davies, M. R. et al (2015). Emergence of Scarlet Fever Streptococcus Pyogenes emm12 Clones In Hong Kong Is Associated With Toxin Acquisition And Multidrug Resistance. Nature Genetics, 47, 84–87.

- Silva-Costa, C., Carrico, J. A., Ramirez, M. & Melo-Cristino, J.(2014) Scarlet Fever Is Caused By A Limited Number of Streptococcus Pyogenes Lineages And Is Associated With The Exotoxin Genes ssa, speA and speC. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 33, 306–310.

- Brosnahan, A.,J., Mantz, M.,J., Squier, C.,A., Peterson, M.,L., Schlievert, P.,M.,(2009) Cytolysins Augment Superantigen Penetration of Stratified Mucosa, Journal of Immunology, 182, 2364-2373.

- Broudy,T.,B., Pancholi,V.,Fischetti, V.,A.(2002) The In Vitro Interaction of Streptococcus Pyogenes With Human Pharyngeal Cells Induces A Phage-Encoded Extracellular DNase, Infection & Immunity,, 70, 2805-2811.

- Lamagni, T. et al (2018). Resurgence of Scarlet Fever In England, 2014-16: A Population-Based Surveillance Study. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 18, 180–187.

- Kasper, K. J. et al(2014). Bacterial Superantigens Promote Acute Nasopharyngeal Infection By Streptococcus Pyogenes In A Human MHC Class II-Dependent Manner. PLoS (Public Library of Science) Pathogens. 10, e1004155.

- Zeppa, J. J. et al (2017). Nasopharyngeal Infection By Streptococcus Pyogenes Requires Superantigen-Responsive Vbeta-Specific T cells. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences. USA, 114, 10226–10231.

- Brouwer, S., Barnett, T.,C., Kasper, K.,J., et al (2020) Prophage Exotoxins Enhance Colonization Fitness In Epidemic Scarlet Fever- Causing Streptococcus Pyogenes, Nature Communications, 6 October.

- Kamochi,M.,Kamochi,F.,Kim,Y.,B.,Sawh S., Sanders, J.,M.,Sarembock, I., et al (1999) P-Selectin And ICAM-1 Mediate Endotoxin-Induced Neutrophil Recruitment And Injury To The Lung And Liver, American Journal of Physiology, 277, 1310-1319.

- Herwald, H., Cramer,H., Morgelin,M.,Russell,W.,Sollenberg, U., Norrby-Teglund, A., et al (2004) M- protein, A Classical Bacterial Virulence Determinant, Forms Complexes With Fibrinogen That Induce Vascular Leakage, Cell, 116, 367-379.

- Menezes, G.,B.,Lee, W.,Y., Zhou,H.,Waterhouse, C,C.,Cara, D.,C.,Kubes,P.,(2009) Selective Down-Regulation of Neutrophil Mac-1 In Endotoxemic Hepatic Microcirculation Via IL-10, Journal of Immunology, 183, 7557-7568.

- Duffy, M.M., Ritter, T., Ceredig, R. and Griffin, M.D. (2011) Mesenchymal Stem Cell Effects on T-Cell Effector Pathways. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2, Article No. 34.

- Gong, J., Meng, H.B., Hua, J., et al. (2014) SDF-1/CXCR4 Axis Regulates Migration of Transplanted Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells towards the Pancreas Rats with Acute Pancreatitis. Molecular Medicine Reports, 9, 1575-1582.

- Yang, B., Bai, B., Liu, C.X., et al. (2013) Effect of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Treatment of Severe Acute Pancreatitis in Rats. Cytotherapy, 15, 154-162.

- He, Z., Hua, J., Qian, D., et al. (2016) Intravenous hMSCs Ameliorate Acute Pancreatitis in Mice via Secretion of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Stimulated Gene/Protein 6. Scientific Reports, 6, Article No. 38438.

- Fang, J. and Zhang, Y. (2017) Icariin, an Anti-Atherosclerotic Drug from Chinese Medicinal Herb Horny Goat Weed. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8, 734.

- Xu, C.Q., Liu, B.J., Wu, J.F., et al. (2010) Icariin Attenuates LPS-Induced Acute Inflammatory Responses: Involvement of PI3K/Akt and NF-κB Signaling Pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology, 642, 146-153.

- Nurnberger, W., Heying, R., Burdach, S., Gobel, U., et al. (1997) C1 Esterase Inhibitor Concentrate in Capillary Leakage Syndrome Following Bone Marrow Transplantation. Annals of Hematology, 75, 95-101.

- Schneider, D.T., Nurnberger, W., Stannigel, H., Bonig, H. and Gobel, U. (1999) Adjuvant Treatment of Severe Acute Pancreatitis with C1 Esterase Inhibitor Concentrate after Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Gut, 45, 733-736.

- Smith, M., Kocher, H.M. and Hunt, B.J. (2010) Aprotinin in Severe Acute Pancreatitis. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 64, 84-92.

- Berling, R., Genell, S. and Ohlsson, K. (1994) High-Dose Intraperitoneal Aprotinin Treatment of Acute Severe Pancreatitis: A Double-Blind Randomized Multi-Center Trial. Journal of Gastroenterology, 29, 479-475

- Gillen,C.,M., Towers,R.,J.,McMillan, D.,J.,Delvecchio, A., Sriprakash, K.,S.,Currie, B.,Kreikemeyer, B., Chhatwal,G.S. Walker, M.,J.,(2002) Immunological Response Mounted By Aboriginal Australians Living In The Northern Territory of Australia Against Streptococcus Pyogenes Serum Opacity Factor, Microbiology, 148, 169-178.

- Courtney,H.,S., Yi-Li, Twal, W.,O.,And Argraves, W.,S.,(2009) Serum Opacity Factor Is A Streptococcal Receptor For The Extracellular Matrix Protein Fibulin-1, Journal of biological Chemistry, 284, 12966-12971.

- Low,D.,E., (2019) Steptococcus Pyogenes, Infectious Disease Advisor, January 19.

- Ramachandran (2019) Tropical Infections of The Heart- Special Focus On Rheumatic Fever And Endomyocardial Fibrosis With Clinical Perspectives, 2nd International Summit On Microbiology & Parasitology, Bangkok (Sukosal), Thailand, October, 24-25 (You Tube).