Archive : Article / Volume 1, Issue 1

- Research Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-3604/003

Neurocognitive sequelae following COVID-19 infection in older adults with and without pre-infection neurocognitive impairment

1 Department of Neurology, Duke University Schoolof Medicine, Durham,North Carolina

2 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

3 Division of Behavioral Medicine & Neurosciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina

4 Institute for Brain Sciences,Duke University, Durham,North Carolina

5 Center for Cognitive Neurosciences, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

Andy J. Liu

Bryce W. Polascik, B.S., Sanya Shah, Jeffrey N. Browndyke, Simon W. Davis, Thomas J. Farrer, Andy J. Liu, (2022). Neurocognitive sequelae following COVID-19 infection in older adults with and without pre-infection neurocognitive impairment. Journal of Covid Research and Treatment. 1(1). DOI: 10.58489/2836-3604/003.

© 2022 Andy J. Liu, M.D., this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 20-11-2022

- Accepted Date: 09-12-2022

- Published Date: 28-12-2022

SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, coronavirus, cognition, neurocognitive, convalescence, PASC

Abstract

In this case report,we describe the clinical characteristics of three older adults aged >65years with cognitive difficulties prior to theirCOVID-19 infection who reported worsening of neurocognitive symptoms in the convalescent COVID-19 phase. Formal neuropsychological testingalong with neuroimaging were included with each patient.

These patients described an initial worseningin cognitive functionafter recovering from the acute phase of COVID19. This case reportdescribes variable recoveryof cognitive abilities in the convalescent stage. The direct effectof the viral infection itselfon cognitive function are well documented. We hypothesize that the persistent inflammatory or immune response in the convalescent COVID-19 stage, more commonly referred to as the indirect mechanism, contributes to the clinical syndromeknown as the Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC).

Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory SyndromeCoronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1]. During the acute infectionperiod, reported central nervous system (CNS) involvement has ranged from acute delirium to meningoencephalitis [2-5]. While these acute neurological symptoms and manifestations have been well-described, the long-term cognitive and neurobehavioral outcomes have yet tobe fully characterized in olderadult convalescent coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patients[1], particularly in those with pre-existing cognitive impairment. Although about 70-80% of infected individuals recover uneventfully without lastingimpairment or complications [6], the remainder develop long-COVID also termed Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC) with symptoms lasting12 weeks or more[7-9], that has been attributed to chronic inflammation with immune activation and dysregulation [10,11].

Characterizing the neuropsychiatric phenotype of older adult COVID-19 patientsduring their convalescent periodis particularly important, especially those with lingering or worsening symptoms, since the relationship betweenSARS-CoV-2 infection and cognitive dysfunction remains unclear.

This case report describes the clinical characteristics of three older adults (aged > 65 years) who reported worseningneuropsychiatric symptoms in the SARS-CoV-2 convalescent period.Specifically, we reportneuroimaging and neuropsychological testing information, which may provide supporting evidence for indirecteffects of chronic inflammation followingCOVID-19 on the brain [10,11]in contrast to direct evidencesuch as acute responseto a viral load. Differing clinical characteristics in the patientsreported here suggest that long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms in COVID-19patients are likely multifactorial, reflecting a combination of residual neurological involvement due to a direct (acute response to viral infection) or indirect (chronic inflammatory response with immune activation and dysregulation) mechanisms [10,11].

Methods

Three older adults (>65years) who noted worsening cognitive difficulties after SARS-CoV-2 infection were evaluated in the Memory Clinic of the Duke Neurological Disorders Clinic.

Electronic medical records were retrospectively reviewed. Examination included a comprehensive neurological evaluation with cognitive screeningusing the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), clinicalneuroimaging, and a subsequent formal neuropsychological evaluation. Prior patient historyand data were collected for comparison with the post-COVID-19 clinical evaluation profiles.

Results

Patient 1 is a 69-year-old male with ahigh school education and a historyof diabetes, hypertension, depression, and a first-order relative and maternal aunt with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease dementia who presented for evaluation of memory loss. The memory loss had been ongoingfor about one year buthad significantly worsened in the five months following his recovery from COVID-19. He had documented antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.

At that time, no vaccine was available. The patient reportedthat he can no longer remember when he had eaten, and evinced navigation issues when driving on familiar roads. Prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection, head computed tomography (CT) without contrast revealed mild bilateral hippocampal atrophy. The patient demonstrated a score of 16 on the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ), 4/8 on AD8 Dementia Screening, 1 on Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),and 20/30 on the MoCA (Table 1). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score was 4, PatientHealth Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)was 10, GeneralAnxiety Disorder-7 (GAD7) was 0, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) was 11. Neuroimaging was notrepeated. Formal neuropsychological evaluation (Table 2) was performed five months after recoveryfrom active COVID-19infection. With premorbid cognitive abilities estimated to be below-average, neurocognitive assessment measureresults revealed isolated difficulties in executive task performance and diminished acquisition and impaired un-cued retrievalon memory assessment measures. Performances on measures of attention and executive function were in the low average to average range on a majority of tests, which is in keepingwith the patient’s premorbid ability estimates. He did display below average abilities for verbal reasoning and complex attention (workingmemory), and he was prone to errors and perseveration duringa problem-solving test. Visual-spatial abilities were commensurate with premorbid estimates. Language abilities were low average for phonemic fluency, but more markedly impaired for semantic fluency, suggesting possible reduction in elaboration of semantic knowledge stores. Confrontational object naming was low average. In terms of memory,acquisition and retrieval of rote verbal information were borderline, suggesting a weaknessin learning and recall.

Retention was 63%and although his recognition memory score was low, he recognized previously learned items. Performance improved on a measure of contextual verbal memory, with learningand recall commensurate with premorbid ability. Visual memory was attenuated for learning and impaired for recall, although he did have normal recognition memory for this visual information. The patient denied mood symptoms on a self-report measurement. These findings indicated frontal/subcortical system dysfunction (Table 2). Other comorbidities includeda history of vitamin B12 deficiency treatedwith B12 injections, atrialfibrillation, congestive heartfailure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea,and morbid obesity.A diagnosis of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD) withoutbehavioral disturbance was assigned in this case,and the patientwas started on donepezil.

Patient 2 is a 68-year-old male with a Master’s degree and a history of anxiety,depression, and attention deficitdisorder (ADHD) who presented four months after recovering from COVID-19 for evaluation of poor memory, inability to “visually map,” and daily “senior moments” as wellas a prolonged period of confusion while driving. He had documented antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 prior to vaccineavailability. He had transient memoryproblems two years priorthat improved after changing his anti-depressant medication (bupropion) dosage. Afterrecovering from his COVID-19 infection, the patient beganto regularly misplace objects and often stop a task midway through, thinking he had completed it. There was no family history of cognitive impairment. Head CT was unremarkable. MRI of the brain demonstrated mild hippocampaland biparietal lobe atrophy, as well as mild cerebral white matter disease. He scored 7/8 on the AD8 Dementia Screening and 27/30on the MoCA (Table1). PHQ-9 was 9, GDS was 2, GAD7 was 16, and NPI was 7. B12 was normal.

Formal neuropsychological evaluation (Table 2) wascompleted six months after recovery from COVID-19infection. With premorbid cognitive abilities estimated to be above- average, formalneuropsychological testing revealed only a few notable findings, which included a reduction in speeded task performance in areas of simple and complex sequencing and basic processing speed. Other areasof testing were average or better than average. These findings were thought to reflect some degree of frontal or subcortical system involvement. Recognizing some evidenceof neurocognitive recovery, a diagnosis of subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) - thoughtto be related to multiple factors, including pre-existing ADHD, mild microvascular ischemia, and history of mood symptoms – was made.

Patient 3 is a 73-year-old male with a bachelor’s degreeand a history of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype of ε3/ε3 and a history of sleep apnea, multinodular goiter, aortic aneurysm, and hypercholesterolemia. He has two brothers, each diagnosed with an unspecified dementia. Prior to contracting COVID-19, he presented to the Duke Memory Disorders clinicfor evaluation of memory difficulties, episodes of confusion, misplacementof belongings, and difficulty remembering drivingroutes. At that time, his global cognitive screening MoCA score was 22/30, reflecting possible mild cognitive impairment (MCI) difficulties (Table 1). Other neurocognitive and psychiatric screening data reinforced the likelihood of MCI, but withgeneral preservation of functional abilities with an AD8 of 3/8 andFAQ of 1. His psychiatric screening data were largely devoid of any self-reported anxiety or depression symptoms with an NPI of 1, GDS of 0, GAD7 of 0, and PHQ-9 of 1.

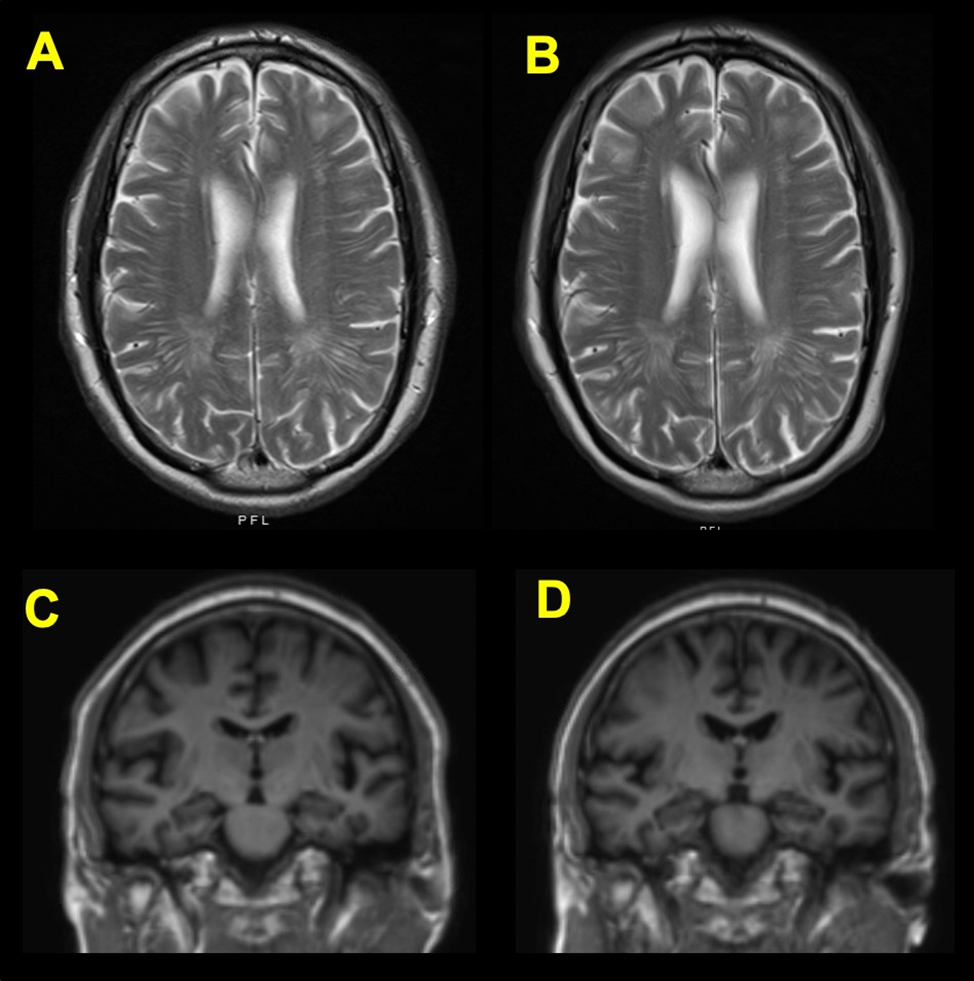

Volumetric neuroimaging (MRI - T1 spoiled gradientecho [SPGR] sequence) failed to demonstrate any appreciable regional mesial temporal lobe or global atrophy patterns. On T2 weighted imaging, he was found to have patchy T2 white matter hyperintensities within the periventricular and deep white matter, likely reflective of mild chronic ischemic microvascular disease without a specific etiology to explain his cognitive symptoms (Figure 1A). NeuroQuant® (CorTech Labs, San Diego, California) analysis estimated bilateral hippocampal volumeat 95% for age (Figure1B). He received a pre-SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis of MCI. Approximately 12 months later,prior to vaccineavailability, he was hospitalized with COVID-19 aftertesting positive for SARS-CoV-2 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). His condition was complicated by acute deliriumwith transient disorientation and viral pneumonia. After fully recovering from the SARS-CoV-2 infection, he noted an increase in subjective memory difficulties over the ensuing monthscompared to his pre-infection baseline. An evaluation determined that he was fully independent for all basic and advanced activities of daily living(ADL). His post-COVID-19 global cognitive screening MoCA score was 23/30, possibly reflecting either stable or slightly improved overall cognition (Table 1). Additional cognitive screening data were consistent with general stability with an AD8 of 3/8. Even though significant changes in functioning were subjectively gauged by the patient (FAQ = 10) relative to his pre-infection baseline (FAQ =1), he remained fully independent on all ADLs. His subjective mood symptomscreening results slightly worsened,although remained non-diagnostic for clinically significant mood disorder with an NPI of 2, GDS of 3, GAD7of 0, and PHQ-9 of 2.Formal neuropsychological evaluation (Table 2) completed 10 months after recovery from COVID-19 infection revealed that performances on measures of attention and executive function were within expectation for reasoning skills. There was at least mild attenuation in other aspects of executive function, including simple and complex sequencing, processing speed, attention, and problem-solving. General visual-spatial abilities were intact. Phonemicfluency was low average and object naming was weak, in the borderline range. In termsof memory, acquisition of rote verbal information was weak, in the borderline range, and delayed recall was impaired, with 0% retention of learned information. Although recognition discrimination was weak compared to same age peers, it appeared that he recognized items previously learned. Otherwise, memory performances on an additional verbal task and visual task were normal. He denied mood symptoms on a self-reported measure. Thus, results on this neuropsychological evaluation revealed difficulties in certain aspectsof executive function, particularly for timed and complex tasks. This impacted executive aspects of additional testingareas including more difficulty on a memory test with higher executive demandand attenuated phonemic fluency. These findings suggested frontal and subcortical system involvement, consistent with imaging evidence of microvascular ischemic change. Deficits in semantic language/confrontational naming was thought to be due to left temporal involvement. There was no indication of medial temporal involvement and thus the consensuswas that there was no amnestic component. In direct comparison with his pre-COVID neuroimaging data (Figures 1A, 1C), post-infection and recovery demonstrated that the patchy hyperintensities within the periventricular and deep white matter remainedunchanged and nonspecific (Figure 1B). NeuroQuant analysis revealed that hippocampal occupancy remained within normal limits (95% of normal) (Figure 1D).

He was diagnosed with mild neurocognitive disorder and non-amnestic MCI without behavioral disturbance.

Figure 1. In axialT2 weighted MRI images, the periventricular whitematter hyperintensities are unchanged and consistent with age both before (A) and two weeks afterthe positive COVID-19 diagnosis(B). In T1 spoiled gradientecho (SPGR) MRI images, the hippocampal volume is similarly unaffected, both before (C) and two weeks after the positive COVID-19 diagnosis (D).

Table 1. National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Montreal CognitiveAssessment (MoCA) Subdomain Index Performance Scores.

|

| Index Scores | |||||

Patient | MoCA Score | Executive | Attention Concentration | Language | Visuospatial | Orientation | Memory |

1 | 20 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

2 | 27 | 13 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

3 (2020) | 22 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 |

3 (2021) | 23 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 2 |

Table 2. Demographics and Formal Neuropsychological Evaluations.

Demographics |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

Case 3 |

Age (years) | 69 | 69 | 73 |

Sex | Male | Male | Male |

Education Race | 12 White | 18 White | 16 Black |

Tests |

|

|

|

TOPF | 37 | 61 | 41 |

Intellectual Functioning |

|

|

|

WAIS-IV GAI |

33 |

67 |

46 |

VCI | 30 | 71 | 47 |

PRI | 38 | 60 | 44 |

Executive Functioning |

|

|

|

TMT A | 48 | 31 | 33 |

TMT B | 39 | 42 | 42 |

WCST Categories (Raw) | 1 | NA | 1 |

Digit Span | 30 | 50 | 37 |

Coding | 37 | 42 | 32 |

Language |

|

|

|

BNT | 38 | 56 | 33 |

FAS | 37 | 49 | 41 |

Animal | 28 | 48 | 44 |

Vocabulary | 33 | 55 | 50 |

Similarities | 33 | 67 | 67 |

Verbal Memory |

|

|

|

HVLT TotalLearning | 35 | 50 | 33 |

HVLT DelayedRecall | 36 | 44 | ≤ 20 |

WMS-IV Logical Memory I | 47 | 52 | 55 |

WMS-IV LogicalMemory II | 40 | 54 | 59 |

Visual Memory |

|

|

|

BVMT TotalLearning | 32 | 60 | 45 |

BVMT DelayedRecall | 24 | 63 | 46 |

Mood |

|

|

|

GDS (Raw) | 5 | 8 | 3 |

NA = Not administered; All scores are T scores (mean of 50, SD of 10) unless indicated.

TOPF = Test of Premorbid Functioning; WAIS = WechslerAdult Intelligence Scale; GAI = General

Ability Index; VCI = Verbal Comprehension Index; PRI = Perceptual ReasoningIndex; TMT = Trail

Making Test; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; BNT = Boston Naming Test; FAS = phonemic

fluency using letters; HVLT = HopkinsVerbal Learning Test; WMS = Wechsler MemoryScale;

BVMT = BriefVisuospatial Memory Test; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale.

Discussion

This case report describes the potential exacerbation and progression of pre-existing cognitive difficulties after recovery from acute COVID-19 infectionin three olderadults who completed formalneuropsychological evaluation. The early PASC period inthese individuals resulted in diagnoses that spanned much of the cognitive spectrumwhich included SCI, MCI, and AD. Longitudinal investigation of convalescent patientsis necessary to allowbetter characterization and insight into the long-termneurological effects of COVID-19 infection. Additionally, a longitudinal study may provideinsight into the likely immune and inflammatory mechanisms that have been postulated to lead to PASC [10,11].

Other potentialcontributory etiologies such as the effect of comorbid conditions, a lengthy hospitalization, intensivecare stays, intubation, oxygenlevels, and even education level may be better understood throughlongitudinal investigation.

The acute symptoms of COVID-19 are now well documented [1]; however,there is currently a gap in knowledge regarding the long-term neurological consequences following COVID-19 infection, particularly the neuropsychiatric sequelae [12] in those who manifest persistent inflammation and immune responses that characterize PASC [10,11]. Several case reports of COVID-19-related changes in mental status have correlated the clinical symptoms with significantly elevated CNS inflammatory markers [13-16]. Intriguingly, neuroinflammationis a key contributor to AD pathogenesis in humans [17]. Such an inflammatory response, hypothesized to contribute to AD, is increasingly appreciated for its capacity to exaggerate downstream impairments in cognitivefunction; therefore, characterization of the inflammatory response using both fluid and imaging biomarkers are critical to provide insight into the development of mental status changes in COVID-19 patients as wellas in those who develop PASC. The cases presented herein demonstrate a worsening clinical trajectory in those alreadyat risk for progression of neurodegenerative disease directly followinginfection with SARS-CoV-2, with Patient 1 continuing to worsen. Over time, however, Patient 2 beginsto show some improvement, and Patient 3 exhibits a morestable clinical trajectory. This case report highlights the importance of better understanding through larger,longitudinal studies why some patientsare able to recover while others develop PASC.Data collected from previous coronavirus outbreaks, including 2002 SARS-CoV and 2012 MERS-CoV, have demonstrated evidence of long-term behavioral health outcomes such asdepression, anxiety, fatigue, and post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as rarer neuropsychiatric syndromes [15,18]. Other neurologic and psychiatric conditions, such as encephalopathy, neuromuscular dysfunction, demyelinating processes, and impaired memory and psychosis, may also follow viral infections [12,18].

The incidence and prevalence of such neurological outcomes following COVID-19are still being explored[18,19]. A retrospective cohort study from the United Kingdom(UK) studied over 236,000 COVID-19 patients and concluded that in the 6 months post-infection, just over 10% with no prior historyof neurologic or psychiatric diseasedeveloped such an ailment, whereas 1/3 with prior history received a diagnosis [18]. Mood disorders and anxiety were more common(31%) than neurologic disorders (3.5%). The progressive memory loss inpatient 1 soon after recovery from COVID-19 highlights the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to adversely affect cognition in an individual with pre-existing memorydifficulties.

Individuals at a higher genetic risk of developing AD-related dementia (ADRD) are xperiencing a higher risk of severeCOVID-19; the risk of severeCOVID-19 for people carrying two ApoE ε4 alleles is doubled (OR = 2.31) compared with the more common ApoE ε3ε3 genotype[15,20] as in patient 3. ThoughPatient 3 carried no ε4alleles, his pre- COVID-19 diagnosis placed him within an at-risk category along the ADRD continuum [20]. Although available studies have described memory loss, confusion, and dementia-like manifestations as a component of acute infection [22,23], our cases illustrate progression along the Alzheimer’s continuum early in the COVID-19 convalescent period. The immediacy of this threat further underscores the importance of closely following older adult convalescent COVID-19 patients given the broad clinical phenotypeof PASC that is now evident from extended follow-up in neurology-based and psychiatry-based clinics. Given the large number of infected individuals duringthis worldwide pandemic, these long-term neurocognitive effectson the human condition may be more significant and far- reaching than have been realized thus far. Althoughthis small case report of 3 male patients without extended follow-upmay be limited by potential retrospective and attribution biases,the findings supportthe need for longitudinal investigation of convalescent patients in a controlled setting. Other externalcontributing factors that may affect cognition, mood,and anxiety shouldalso be considered and betterunderstood in individuals with PASC. Such work will help furthercharacterize these observations and provide insight into their pathophysiology as we striveto understand the long-term neurocognitive and psychiatric effects of SARS-CoV-2 in infected individuals. Following recovery from the direct insultof active COVID-19disease, chronic inflammation with immune activation and dysregulation in PASC [10,11] may result in a more rapid and progressive neurocognitive trajectory in some individuals with comorbid neuropsychiatric disorders or in those who are at risk for developing such. Larger longitudinal studies are needed to further characterize these observations.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflict of Interest

There are noconflicts of interest to disclose.

Declaration of Interest

The authorsreport that there are no financial or non-financial competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data was included in the submitted manuscript. Other data may be available only on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions since this information contains Protected Health Information (PHI). Each patient included in this manuscript signed a Consent-To-Publishform. Thus, the data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the

corresponding author[AJL]. Other than what has been included in this manuscript submission, the data are otherwise not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet 2021: 397: 220-232.

- de Sousa Moreira JL, Barbosa SMB, Vieira JG, Chaves NCB, Felix EBG, Feitosa PWG, et.al. The psychiatric and neuropsychiatric repercussions associated with severe infections of COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Pro Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2021; 106: 110159.

- Frontera JA, Sabadia S, Lalchan R, Fang T, Flusty B, Millar-Vernetti P, et al. A prospective study of neurologic disorders in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in New York City. Neurology 2021; 96(4): e575-e586.

- Kandemirli SG, Dogan L, Sarikaya ZT, Kara S, Akinci C, Kaya D, et al. Brain MRI findings in patients in the intensive care unit with COVID-19 infection. Radiology 2020; 297(1): E232-E235.

- Rabinovitz B, Jaywant A, Fridman CB. Neuropsychological functioning inn severe acute respiratory disorders caused by the coronavirus: implications for the current COVID-19 pandemic. 2020; 34(7-8): 1453-1479.

- Liu B, Jayasundara D, Pye V, Dobbins T, Dore GJ, Matthews G, et al. Whole of population-based cohort study of recovery time from COVID-19 in New South Wales Australia. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021; 12: 100193 (epub).

- Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, Ba DM, Parsons N, Poudel GR, et al. Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4(10): e2128568.

- Whitaker M, Elliott J, Chadeau-Hyam M, Riley S, Darzi A, Cooke G, et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community study of 606,434 people in England. Nat Commun 2022; 13(1): 1957.

- Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, McDonald D, Magedson A, Wolf CR, et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4(2): e210830.

- Peluso MJ, Lu S, Tang AF, Durstenfeld MS, Ho HE, Goldberg SA, et al. Markers of immune activation and inflammation in individuals with postacute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Infect Dis 2021; 224(11): 1839-1848.

- Proal AD, VanElzakker MB. Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): an overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front Microbiol 2021; 12: 698169.

- Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 87: 34-39.

- Benameur K, Agarwal A, Auld SC, Butters MP, Webster AS, Ozturk T, et al. Encephalopathy and encephalitis associated with cerebrospinal fluid cytokine alterations and coronavirus disease, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26(9): 2016-2021.

- Duong L, Xu P, Liu A. Meningoencephalitis without respiratory failure in a young female patient with COVID-19 infection in downtown Los Angeles, early April 2020.Brain Behav Immun 2020; 87: 33.

- Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: asystematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7(7): 611-627.

- Salluh JIF, Want H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damlugi A, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015;350: h2538.

- Molinuevo JL, Ayton S, Batrla R, Bednar MM, Bittner T, Cummings J, et al. Acta Neurpathol 2018; 136(6): 821-853.

- Roy D, Ghosh R, Dubey S, Dubey MJ, Benito-Leon J, Ray BK. Neurological and neuropsychiatric impacts of COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Neurol Sci 2021; 48(1): 9-24.

- Taquet M, Geddes JR, Husain M, Luciano S, Harrison PJ. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8(5): 416-427.

- Kuo CL, Pilling LC, Atkins JL, Masoli JAH, Delgado J, Kuchel GA, et al. ApoE e4e4 genotype and mortality with COVID-19 in UK Biobank. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2022; 75(9): 1801-1803.

- Campbell NL, Unverzagt F, LaMantia MA, Khan BA, Boustani MA. Risk factor for the progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Clin Geriatr Med 2013; 29(4): 873-893.

- Priftis K, Algeri L, Villella S, Spada MS. COVID-19 presenting with agraphia and conduction aphasia in a patient with left-hemisphere ischemic stroke. Neurol Sci 2020; 41(12): 3381-3384.

- Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, Davies NWS, Pollak TA, Tenorio EL, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7(10): 875-882.