Article In Press : Article / Volume 3, Issue 2

- Review Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-2330/022

Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Patients- Review

1Senior Consultant Department of Critical Care Medicine Utkal Institute of medical science, Bhubaneswar, India

2Associate ConsultantDepartment of Critical Care Medicine Utkal Institute of medical science, Bhubaneswar, India

Biswabikash Mohanty*

Biswabikash Mohanty, Santi Swaroop Pattanaik, Archana Palo, (2024). Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Patients- Review. Journal of Clinical and Medical Reviews. 3(2); DOI: 10.58489/2836-2330/022

© 2024 Biswabikash Mohanty, this is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 12-08-2024

- Accepted Date: 17-08-2024

- Published Date: 17-08-2024

Abstract

It is well known that nutritional support, should be provided to all critically ill patients which influences their clinical outcome. Malnutrition in critically ill patients is associated with impaired immune function and impaired ventilator drive, leading to prolonged ventilator dependence, increased infectious morbidity and mortality. Enteral nutrition is always the preferred mode of nutrition in critically ill patients due to less severe complications and better patient outcomes, decreased hospital cost and length of stay. This review will discuss about the recent updates about the role of enteral nutrition in critically ill patients.

Introduction

A 52-year-old male presented with dysphagia and reduced intake for 2 months. Within the 3 months, he had lost approximately 30% of his body weight. His current BMI is 17.5 kg/m

2. On admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), there was mild hypomagnesemia and the rest of the electrolytes were normal. On endoscopy, a hypopharyngeal ulcerating lesion extending to the esophagus was found. Biopsy was taken and an orogastric tube was inserted under endoscopic guidance. Enteral nutrition was started at 25 kcal/kg/day. Profound hypophosphatemia developed on day 5 with worsening hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia. parenteral phosphate was administered and feeding was resumed at a slower rate

How do you define malnutrition?

Malnutrition is a nutritional imbalance diagnosed by history and physical examination. At least 2 from any of the following are needed to support the diagnosis of malnutrition:

-Insufficient energy intake (less than 50 percent of energy requirement for > 1 month).

-Percentage of weight loss (less than 20 percent in over 1 year).

-Reduction of muscle mass (wasting at temples, clavicles, thighs, and calves).

-Diminution of subcutaneous fat (loss at orbits, triceps, or fat overlying ribs).

-Fluid accumulation (not related to fluid overload from another combination).

-Reduced grip strength.[1]

What are the screening tools for nutritional assessment in critically ill patients?

Nutritional assessment should be done at admission for all high-risk patients admitted to the ICU [3]. Targeting enteral nutrition in critically ill patients at high risk of malnutrition has resulted in better outcomes.[2]

How much energy and protein is required in a critically ill patient?

The most common approach is to estimate caloric requirements as 25 kcal/kg/day. As per recent ESPEN guidelines, it is recommended that 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day protein can be delivered progressively in critically ill patients [2]. Predictive equations that estimate energy expenditure are often inaccurate compared to indirect calorimetry. The most accurate approach recommended by recent ESPEN guidelines is indirect calorimetry which directly measures CO2 generation and O2 consumption. Other methods include estimating resting energy expenditure via VCO2 (carbon dioxide production) from the ventilator and rewritten Weir formula (REE = VCO2 * 8.2) or using VO2 (oxygen consumption) from a pulmonary artery catheter via the Fick method [6,7].

Table No 1: Nutritional Risk Assessment Tools

| Score | Parameters | Interpretation | Remarks |

| NRS 2002 | Recent dietary intake, Disease severity, Weight Loss | NRS greater than 3- severe risk of malnutrition | -Poor prediction in critically-ill patients -Challenges in the assessment of weight loss and dietary intake.[4] |

| NUTRIC SCORE | Age, APACHE II, SOFA, Number of comorbidities, Days from hospital to ICU admission, IL-6 | Greater than 6-worse clinical outcomes | Nutritional parameters were not taken into consideration.[4] |

| SUBJECTIV GLOBAL ASSESSMENT | Subcutaneous fat, Muscle wasting, Fluid retention, weight change, Recent food intake, GI symptoms, Functional capacity | divided into 3 classes- A- no malnutrition B- Moderate malnutrition C- Severe malnutrition | Severity of illness was not included. Difficult to assess weight loss and food history.[4] |

When and how to start enteral nutrition in a critically ill patient?

According to ESPEN and ASPEN guidelines, enteral nutrition should be initiated as early as possible within 24-48 hours of admission to ICU [2,5]. Enteral nutrition can be subsequently advanced to a70 percent calories target over the next 3-7 days, or as tolerated by the patient [2]. Whenever possible, it is advisable to meet the 100 percent protein target for these patients [8].

Enumerate the different feeding strategies and the evidence to support this.

Usual dose (less than 1.2g/kg/day) vs higher dose of protein (2.2g/kg/day)

There is no reported decrease in mortality or hospital stay on delivering higher doses of protein to critically ill patients. On the contrary, higher doses of protein are reported to have worsened outcomes for patients with acute kidney injury and greater severity of illness when compared to the usual dose of protein delivery [9].

Energy dense feeds (1.5 kcal/ml) vs routine feed (1.0 kcal/ml)

The TARGET study found no difference in mortality in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients getting energy-dense feeds as compared to routine feeds whereas, GI intolerance and metabolic effects were higher in the group getting energy-dense feeds. There was no difference in mortality in other studied subgroups (age, trauma, sepsis, medical or surgical patients) [10].

Permissive underfeeding vs standard enteral feeding

The PERMIT trial shows that permissive underfeeding with full protein requirements appeared safe in critically ill patients [11]. In patients with acute lung injury who were ventilated, the EDEN trial did not observe any difference in outcomes in terms of mortality at 60 days, ventilator-free days, and, infectious complications when a comparison was done between trophic feeding strategy with full feeding strategy [12].

Intermittent feeding vs continuous feeding strategy

Greater incidence of distension of abdomen, diarrhea, and, longer length of ICU stay has been reported in patients who are critically ill and received the intermittent feeding strategy and lesser incidence of constipation when compared with continuous feeding strategies [13,14].

What are the factors leading to delayed initiation of enteral nutrition?

In most cases, enteral nutrition should be started as early as possible except in some scenarios like obstructive ileus, gastro-intestinal ischemia, high output fistula, active upper GI bleed, and high/increasing doses of vasopressors [2].

What are the risk factors for enteral feeding intolerance in critically ill patients?

Gastric feed intolerance, a condition characterized by the inability to tolerate enteral feeds can impede optimal nutrition delivery and lead to complications in critically ill patients [15].

Table no 2- Risk factors for enteral feeding intolerance

| Severity of illness | Higher APACHE 2 scores, SevereSepsis, Burns |

| Gastro-intestinal dysfunction | Pre-existing gastrointestinal disorders-inflammatory boweldisease, gastroparesis, gastrointestinal obstruction |

| Sedationand analgesia | Administration of Sedatives, Opioids, and Neuromuscular Blockers |

| Hemodynamic instability | patientswith hemodynamic instability, shock, and high vasopressor states |

| Medication interactions | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Corticosteroids and Antibiotics |

| Hyperglycemia | Commonly observed in stress hyperglycemia or critically ill patients. |

| Nutritional formulations | High osmolality, high fiber content, and fat concentration. |

How do you assess enteral feeding intolerance and the importance of gastric residual volume (GRV) measurements?

As per ASPEN guidelines, for clinical evaluation of feeding intolerance watch for symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal distension, and respiratory compromise [5]. Many institutions still follow protocols to use GRV [gastric contents in the stomach after a feeding, or medication has been administered] as the indicator for feeding intolerance. Since each patient is unique and the clinical context needs consideration, ASPEN does not support particular cutoff values for GRVs that require action [5]. While comparing a protocol of enteral nutrition management without residual gastric volume monitoring to a similar protocol including residual gastric volume monitoring in terms of protection against VAP, Reignier et al found that the two protocols were comparable without any superiority of either protocol [16]. Interruptions of enteral nutrition delivery due to residual gastric volume monitoring lead to inadequate feeding and should not be a part of the standard care of critically ill patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation and early enteral nutrition. A cutoff value of 500 ml for GRV could be considered as per the REGANE study for feeding protocols that use a cut-off value for GRV [17]. Regular and repeated evaluation of GRV using a higher threshold may be warranted to identify patients who may benefit from interventions to manage enteral feed intolerance.

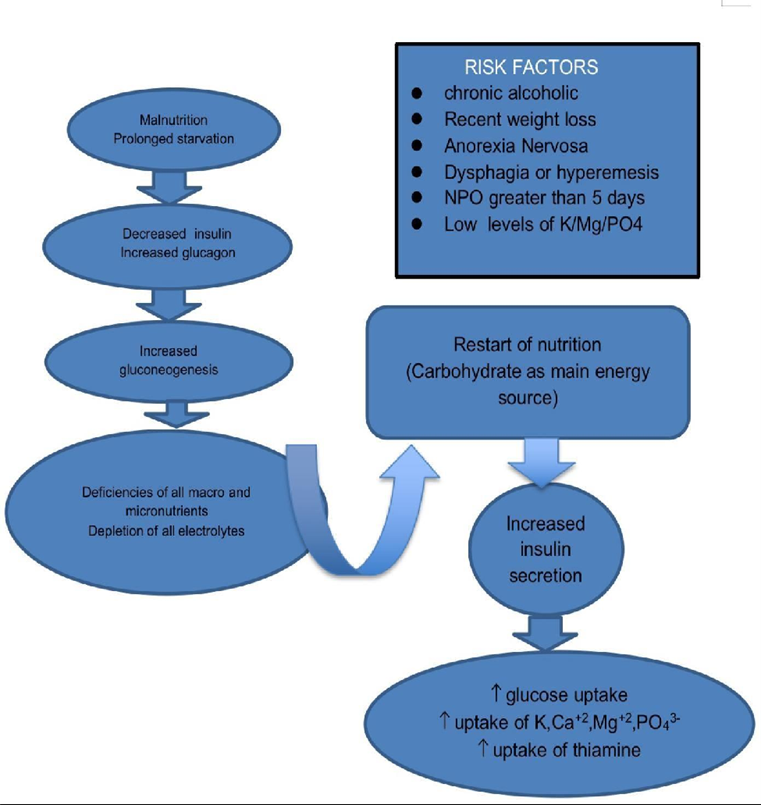

Define refeeding syndrome? What are its risk factors? How to diagnose and how to manage it?

Refeeding syndrome is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition that can occur when someone is severely malnourished or prolonged starvation and undergoes initiation of nutritional support in full phase. In this regard, calories may be from any source: oral diet, enteral nutrition (EN), PN, or intravenous (IV) dextrose (e.g., 5 Percent dextrose solution) [18].

What are the disease-specific nutrition strategies?

Table 3: Disease specific nutrition strategies

| Sl No | Specific disease | Target calorie intake | Total protein intake | Specific consideration |

| 1 | AKI | 25-30 kcals/kg actual body weight/day. | 1.2-2 g/kg actual BW/day | Use standard enteral formula with low phosphate and potassium |

| 2 | CRRTor HD | 25-30 kcals/kg actual BW/day | 2.5 g/kg body weight | |

| 3 | Liver Disease | 25-30 kcals/kg/day | 1.2-2 g/kg /day | -Avoid restricting protein -Standard EN formula instead of a formula with Branched chain amino acid (BCAA) |

| 4 | Sepsis | 10–20 kcal/h or up to 500 kcal/d) for initial phase advancing as tolerated after 24–48 hours to>80% of target energy goal over the first week. | 1.2–2 g protein/kg/d. | Immune-modulating formulas not to be used routinely No Role of selenium, zinc, and antioxidant supplementation |

| 5 | Polytrauma | Energy 20–35 kcal/kg/d, depending on the phase of trauma. | 1.2–2 g/kg/d | Immune-modulating formulations containing arginine and Glutamine to be considered in severe trauma (ESPEN 2023) |

| 6 | Burn | 1.5–2 g/kg/d. | Very early initiation of EN (within 4–6 hours of injury) | |

| 7 | Obese | Indirect Calorimetry to be used to estimate. Adjusted body weight can be used if indirect calorimetry is not available | 1.3gm/kg | -Isocaloric high protein diet -Preferentially guided by IC or urinary nitrogen loss [4]. |

Pic1: Pathophysiology of Refeeding Syndrome

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF REFEEDING SYNDROME

It is very important to assess patients at high risk for refeeding syndrome. Initiate with 100–150 g of dextrose or 10–20 kcal/kg for the first 24 hours; advance by 1/3rd of the goal every 1 to 2 days. This includes both enteral and parenteral glucose [18]. In patients with moderate to high risk of refeeding syndrome with low electrolyte levels, it is prudent to put on hold the initiation or increase of calories, until electrolytes are supplemented and normalized [18,19]. Monitoring electrolyte levels, thiamine supplementation (100mg/day for 5-7 days), substituting vitamins and micronutrients, aggressive electrolyte correction, reducing caloric intake, and gradual advancement with regular reassessment of feeding intolerance holds the key to management of refeeding syndrome [18,20].

Conclusion

Enteral nutrition stands an important pillar in the comprehensive care of critically ill patients, offering a tailored approach that supports recovery and long-term outcomes. By prioritizing the integration of evidence-based practices and personalized patient care, health care providers can continue to make significant strides in optimizing nutrition delivery and ultimately improving the quality of life for their patients in critical care settings.

References

- White, J. V., Guenter, P., Jensen, G., Malone, A., Schofield, M., Force, A. M. T., & Academy Malnutrition Work Group. (2012). Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(5), 730-738.

- Singer, P., Blaser, A. R., Berger, M. M., Alhazzani, W., Calder, P. C., Casaer, M. P., ... & Bischoff, S. C. (2019). ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clinical nutrition, 38(1), 48-79.

- Mehta, Y., Sunavala, J. D., Zirpe, K., Tyagi, N., Garg, S., Sinha, S., ... & Kadhe, G. (2018). Practice guidelines for nutrition in critically ill patients: a relook for Indian scenario. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 22(4), 263.

- Narayan, S. K., Gudivada, K. K., & Krishna, B. (2020). Assessment of nutritional status in the critically ill. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, 24(Suppl 4), S152.

- McClave, S. A., Taylor, B. E., Martindale, R. G., Warren, M. M., Johnson, D. R., Braunschweig, C., ... & Compher, C. (2016). Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN). JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition, 40(2), 159-211.

- Flancbaum, L., Choban, P. S., Sambucco, S., Verducci, J., & Burge, J. C. (1999). Comparison of indirect calorimetry, the Fick method, and prediction equations in estimating the energy requirements of critically ill patients. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 69(3), 461-466.

- Kagan, I., Zusman, O., Bendavid, I., Theilla, M., Cohen, J., & Singer, P. (2018). Validation of carbon dioxide production (VCO 2) as a tool to calculate resting energy expenditure (REE) in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: A retrospective observational study. Critical Care, 22, 1-6.

- Singer, P., Blaser, A. R., Berger, M. M., Calder, P. C., Casaer, M., Hiesmayr, M., ... & Bischoff, S. C. (2023). ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clinical Nutrition, 42(9), 1671-1689.

- Heyland, D. K., Patel, J., Bear, D., Sacks, G., Nixdorf, H., Dolan, J., ... & Compher, C. (2019). The effect of higher protein dosing in critically ill patients: a multicenter registry‐based randomized trial: the EFFORT trial. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 43(3), 326-334.

- Chapman, M., Peake, S. L., Bellomo, R., Davies, A., Deane, A., Horowitz, M., ... & Young, P. (2018). Energy-dense versus routine enteral nutrition in the critically ill. The New England journal of medicine, 379(19), 1823-1834.

- Arabi, Y. M., Aldawood, A. S., Haddad, S. H., Al-Dorzi, H. M., Tamim, H. M., Jones, G., ... & Afesh, L. (2015). Permissive underfeeding or standard enteral feeding in critically ill adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(25), 2398-2408.

- Heart, T. N. (2012). Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association, 307(8), 795.

- Qu, J., Xu, X., Xu, C., Ding, X., Zhang, K., & Hu, L. (2023). The effect of intermittent versus continuous enteral feeding for critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Nutrition, 10, 1214774.

- Heffernan, A. J., Talekar, C., Henain, M., Purcell, L., Palmer, M., & White, H. (2022). Comparison of continuous versus intermittent enteral feeding in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care, 26(1), 325.

- Heyland, D. K., Ortiz, A., Stoppe, C., Patel, J. J., Yeh, D. D., Dukes, G., ... & Day, A. G. (2021). Incidence, risk factors, and clinical consequence of enteral feeding intolerance in the mechanically ventilated critically ill: an analysis of a multicenter, multiyear database. Critical care medicine, 49(1), 49-59.

- Blaser, A. R., Starkopf, J., Kirsimägi, Ü., & Deane, A. M. (2014). Definition, prevalence, and outcome of feeding intolerance in intensive care: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 58(8), 914-922.

- Reignier, J., Mercier, E., Le Gouge, A., Boulain, T., Desachy, A., Bellec, F., ... & Lascarrou, J. B. (2013). Effect of not monitoring residual gastric volume on risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults receiving mechanical ventilation and early enteral feeding: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 309(3), 249-256.

- Montejo, J. C., Minambres, E., Bordeje, L., Mesejo, A., Acosta, J., Heras, A., ... & Manzanedo, R. (2010). Gastric residual volume during enteral nutrition in ICU patients: the REGANE study. Intensive care medicine, 36, 1386-1393.

- da Silva, J. S., Seres, D. S., Sabino, K., Adams, S. C., Berdahl, G. J., Citty, S. W., ... & Ayers, P. (2020). ASPEN Consensus Recommendations for Refeeding Syndrome (vol 35, pg 178, 2020). NUTRITION IN CLINICAL PRACTICE, 35(3), 584-585.

- Friedli, N., Odermatt, J., Reber, E., Schuetz, P., & Stanga, Z. (2020). Refeeding syndrome: update and clinical advice for prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Current opinion in gastroenterology, 36(2), 136-140.