Archive : Article / Volume 2, Issue 3

Case Report | DOI: https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-2411/022

Reimagining the Role of General Practitioners as Gatekeepers in South African Healthcare- A Review Focusing on Medical Schemes

Council for Medical Schemes, Policy Research, and Monitoring, Pretoria, South Africa.

Correspondng Author: Michael Mncedisi Willie

Citation: Michael Mncedisi Willie (2023). Reimagining the Role of General Practitioners as Gatekeepers in South African Healthcare- A Review Focusing on Medical Schemes 2(3). DOI: 10.58489/2836-2411/022

Copyright: © 2023 Michael Mncedisi Willie, this is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received Date: 2023-06-12, Received Date: 2023-06-12, Published Date: 2023-08-18

Abstract Keywords: General practitioners, gatekeepers, South African healthcare, medical schemes, primary care, access to healthcare.

Abstract

This review provides insights into the role of GPs as gatekeepers in the South African healthcare system and emphasizes the importance of reimagining and reevaluating their role within the context of evolving healthcare reforms and the changing dynamics of medical schemes. The findings contribute to the ongoing discussion on optimizing the gatekeeping function to ensure equitable access to healthcare services while promoting efficient resource allocation and high-quality care.

Introduction

The role of general practitioners (GPs) as gatekeepers in the South African healthcare system has been a topic of debate and discussion in recent years [1-2]. The concept of gatekeeping refers to the practice of requiring patients to obtain a referral from a primary care physician, usually a GP, before accessing specialized or hospital-based care [3-4].

Historically, gatekeeping was implemented in many healthcare systems, including South Africa, to manage healthcare costs, ensure appropriate utilization of services, and facilitate coordinated care [4]. The idea was that GPs, as the first point of contact for patients, would triage and manage a majority of healthcare needs, referring patients to specialists only when necessary [5-6].

However, there has been a growing recognition that the traditional gatekeeping model may have limitations and potential drawbacks [7-8]. Critics argue that strict gatekeeping can lead to delays in accessing necessary care, particularly for patients with urgent or complex conditions [4,9]. It can also create barriers to specialized care, as patients may face additional administrative burdens or lengthy waiting periods for specialist consultations [10-11].

Utilization of GP services- Medical schemes

General Practitioner (GP) services can indeed occur in an out-of-hospital setting and are primarily intended to be preventive [12]. General practitioners, also known as primary care physicians or family doctors, provide a wide range of healthcare services to individuals in the community [13]. The primary goal of GP services is to promote preventive care and maintain overall health and well-being [14]. GPs are trained to diagnose and treat a variety of common illnesses and conditions, as well as provide routine check-ups, vaccinations, and screenings [15]. They also offer health education and advice to help patients make informed decisions about their lifestyle choices and manage chronic conditions [16].

GPs play a crucial role in identifying and managing health issues before they worsen or necessitate specialized care [17-18]. This proactive approach diminishes the likelihood of chronic diseases, enables early detection of illnesses, and fosters healthy behaviors [19]. Accessible through private clinics, community health centers, and occasionally through home visits, GP services are commonly covered by health insurance or can be self-funded [19].

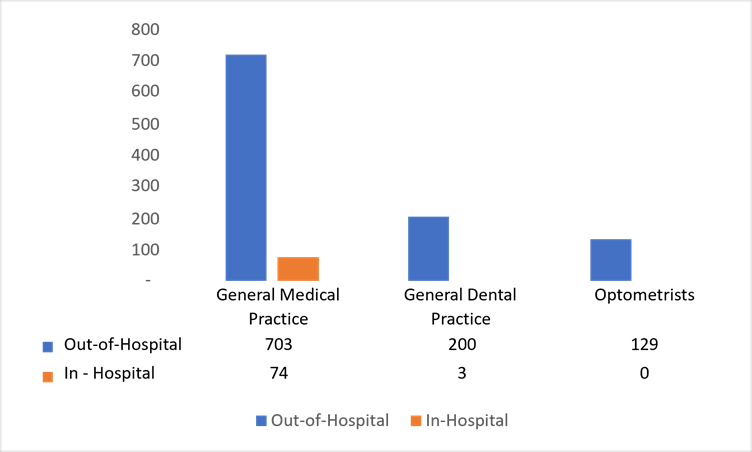

Figure 1 below depicts the number of beneficiaries visiting each of the selected three primary healthcare service providers [20]. According to the CMS Industry Report, 7% of beneficiaries used GP services inside hospitals, while 70% of beneficiaries used GP services outside hospitals [20]. Compared to the low percentage of hospital-based services, 20% of beneficiaries used dental care outside of the hospital [20]. Thirteen percent of people used optometry services which mostly took place outside of a hospital setting [20].

Fig 1: Average number of patients per 1 000 beneficiaries (ratio) Source CMS Industry Report [20].

Health expenditure – Medical schemes

A recent study delved into the healthcare expenditure on general practitioners (GPs) within South African medical schemes, investigating crucial aspects such as the average cost per GP visit, co-payment levels, and the GP-to-member ratio [20]. The findings presented a concerning narrative, revealing a decline in healthcare spending on GPs over time, ultimately undermining their pivotal role as gatekeepers. This study shed light on the study's implications, emphasizing the need for reprioritization and a renewed emphasis on the gatekeeping role of GPs to enhance the quality of care [20].

GPs accounted for just over 9% of healthcare expenditure in 2007, which significantly dwindled to less than 6% in 2018, this further declined to less than 5% in 2021 [21,22]. This decline not only reflects a shift in benefit design within medical schemes but also highlights a disturbing trend of underutilization of GP-related services. It is imperative to recognize the importance of GPs as gatekeepers, responsible for coordinating patient care, ensuring appropriate referrals, and promoting preventive measures [4].

According to the CMS industry report in 2018, 7.2 million beneficiaries had visited a general medical practice at least once, representing 81% of all beneficiaries. The table further depicts that 3 out of four GP-related claims were paid from the risk pool while the balance was paid from PMSA. According to the analysis, there is a funding gap in the claims made for various PHC-related services such as that of GPs. There is a deficit of nearly R1 billion in claims for general practitioner services, which comes to R984 million.

Table 1: Benefits paid for preventative services: 2018.

| Total Amount Claimed (R) | Total Benefits paid. by schemes (R) | Paid by a member. (Est. OOP) (R) | % Paid from risk | |

| General Medical Practice | 11,820,581,517 | 10,836,474,335 | 984,107,183 | 75% |

Source: Derived from CMS Industry Report [22]

Another alarming discovery was the high co-payment levels associated with GP consultations. Co-payments reaching up to 39% of the claimed amount can place a substantial burden on patients seeking primary healthcare services. This financial strain may discourage individuals from seeking timely medical attention, ultimately affecting their overall health outcomes. It is crucial to address these exorbitant co-payment levels to ensure equitable access to primary healthcare services for all.

Human resources factor– GP services

The study finds variations in the GP-to-member ratio across provinces, with an average of 2.1 GPs per 1000 beneficiaries. This disparity indicates that there is an imbalance in the resources and availability of healthcare, which may make it more difficult for some areas to gain access to necessary medical treatments. Equalizing the distribution of GPs across provinces is essential to ensure adequate primary healthcare services for all South Africans.

To reverse the declining trend in healthcare expenditure on GPs and restore their vital role as gatekeepers, a concerted effort is required. Reprioritizing the role of GPs within the benefit design process is paramount. Medical schemes must recognize the significance of GPs in providing comprehensive and coordinated care, fostering a system that encourages patients to seek primary care first. By emphasizing the gatekeeping function, medical schemes can enhance the quality of care, improve patient outcomes, and reduce the strain on the healthcare system.

Conclusion

The findings of the study highlight a concerning decline in access to primary healthcare benefits services. Therefore, it is crucial to reassess benefit design policies to guarantee affordable and easily accessible primary healthcare services for all medical scheme members. By emphasizing preventive care and early intervention facilitated by the gatekeeping role of GPs, medical schemes can effectively tackle health issues before they become severe, leading to a reduction in the burden placed on specialized care facilities.

The study's findings urge us to reconsider the declining investment in GPs within South African medical schemes. Recognizing their role as gatekeepers and reprioritizing their function in the benefit design process is crucial to enhance the quality of care and ensure equitable access to primary healthcare services. Through the implementation of measures aimed at addressing elevated co-payment levels and reducing the disparity in GP-to-member ratios, South Africa can establish a healthcare system that prioritizes primary care and fosters healthier communities. This endeavor holds the promise of improving the general well-being of all South Africans, with the added potential of generating cost savings.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Schmalstieg-Bahr, K., Popert, U. W., & Scherer, M. (2021). The role of general practice in complex health care systems. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 680695.

- Blinkenberg, J., Pahlavanyali, S., Hetlevik, Ø., Sandvik, H., & Hunskaar, S. (2019). General practitioners’ and out-of-hours doctors’ role as gatekeeper in emergency admissions to somatic hospitals in Norway: registry-based observational study. BMC health services research, 19(1), 1-12.

- Forrest, C. B. (2003). Primary care gatekeeping and referrals: effective filter or failed experiment? BMJ, 326(7391), 692-695.

- Sripa, P., Hayhoe, B., Garg, P., Majeed, A., & Greenfield, G. (2019). Impact of GP gatekeeping on quality of care, and health outcomes, use, and expenditure: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice, 69(682), e294-e303.

- Salisbury, C., Murphy, M., & Duncan, P. (2020). The impact of digital-first consultations on workload in general practice: modeling study. Journal of medical Internet research, 22(6), e18203.

- Tzartzas, K., Oberhauser, P. N., Marion-Veyron, R., Bourquin, C., Senn, N., & Stiefel, F. (2019). General practitioners referring patients to specialists in tertiary healthcare: a qualitative study. BMC family practice, 20, 1-9.

- Welbers, K., & Opgenhaffen, M. (2018). Social media gatekeeping: An analysis of the gatekeeping influence of newspapers’ public Facebook pages. New Media & Society, 20(12), 4728-4747.

- Olsen, R. K., Solvoll, M. K., & Futsæter, K. A. (2022). Gatekeepers as safekeepers—Mapping audiences’ attitudes towards news media’s editorial oversight functions during the COVID-19 crisis. Journalism and Media, 3(1), 182-197.

- Garrido, M. V., Zentner, A., & Busse, R. (2011). The effects of gatekeeping: a systematic review of the literature. Scandinavian journal of primary health care, 29(1), 28-38.

- Ezeonwu, M. C. (2018). Specialty-care access for community health clinic patients: processes and barriers. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare, 109-119.

- Schwarz, T., Schmidt, A. E., Bobek, J., & Ladurner, J. (2022). Barriers to accessing health care for people with chronic conditions: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1-15.

- Wilson, T., Roland, M., & Ham, C. (2006). The contribution of general practice and the general practitioner to NHS patients. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99(1), 24-28.

- Mash, R., Gaede, B., & Hugo, J. J. F. (2021). The contribution of family physicians and primary care doctors to community-orientated primary care. South African Family Practice, 63(1).

- Van Weel, C., & Kidd, M. R. (2018). Why strengthening primary health care is essential to achieving universal health coverage. Cmaj, 190(15), E463-E466.

- Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457-502.

- Paterick, T. E., Patel, N., Tajik, A. J., & Chandrasekaran, K. (2017, January). Improving health outcomes through patient education and partnerships with patients. In Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings (Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 112-113).

- Marcussen, M., Titlestad, S. B., Lee, K., Bentzen, N., Søndergaard, J., & Nørgaard, B. (2021). General practitioners’ perceptions of treatment of chronically ill patients managed in general practice: An interview study. European Journal of General Practice, 27(1), 103-110.

- Damarell, R. A., Morgan, D. D., & Tieman, J. J. (2020). General practitioner strategies for managing patients with multimorbidity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Family Practice, 21(1), 1-23.

- Basu, S., Andrews, J., Kishore, S., Panjabi, R., & Stuckler, D. (2012). Comparative performance of private and public healthcare systems in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS medicine, 9(6), e1001244.

- Council for Medical Schemes (CMS). (2022). CMS Industry Report 2021. Pretoria

- Council for Medical Schemes (CMS). (2008). CMS Annual Report 2007. Pretoria.

- Council for Medical Schemes (CMS). (2019). CMS Annual Report 2018. Pretoria.