Article In Press : Article / Volume 3, Issue 2

- Review Article | DOI:

- https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-8851/020

Emergence and Relevance of Classification systems in Aphasia

1Post Graduate student, AIISH Mysuru

2Assistant Professor in Language Pathology, Centre of SLS, AIISH Mysuru

Abhishek BP*

Subhiksha M, Abhishek BP, (2024). Emergence and Relevance of Classification systems in Aphasia. Neurons and Neurological Disorders. 3(2); DOI: 10.58489/2836-8851/020

© 2024 Abhishek BP, this is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Received Date: 09-08-2024

- Accepted Date: 17-08-2024

- Published Date: 24-08-2024

Classification, Assessment, Management, Approaches, Evolution.

Abstract

The present review focuses on giving a broad view on the historical developments in aphasiology. The considerations of these theoretical aspects, equips the clinician with knowledge about variable disorder characteristics, thereby, leading to a strong clinical and research foundation. Several standardized assessment tools and management approaches are designed based on the classification of the aphasic syndrome. Depending on the clinical protocol of a particular setup, it is also observed that a thorough historical background helps with rehabilitation of persons with aphasia in different stages of recovery.

Introduction

Aphasia is an acquired language disorder characterized by impairments in comprehension of spoken or written language, difficulty in producing speech, deficits in naming and repetition, and impairments in reading and writing, all of which variably occurs due to brain damage [1]. The clinical semiology of aphasia has led to various challenges to the aphasiologists around the globe. Even to this day, these challenges occur due to the enigma in the understandings about the original nature of aphasia, its classification systems and the clinical decisions for appraisal and amelioration of individuals with aphasia [2]. The evolution and historical underpinnings of the concept of aphasia will provide directions to the plausible ways to deal with the challenges in clinical and research practices [3]. Therefore, this chapter covers important historical aspects about the aphasic syndrome along with the need and the approaches that arose to classify aphasia.

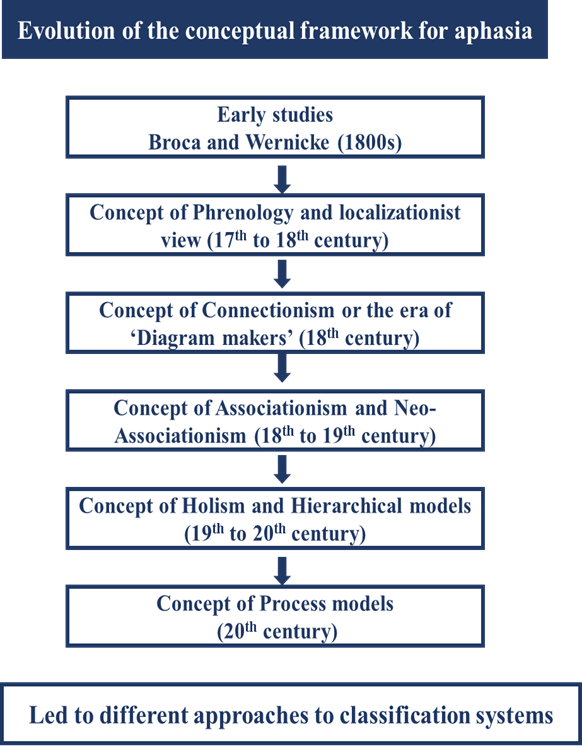

Advent of the concept of aphasia

The ideas about aphasia started in the 15th century, when aphasia was believed to be a memory disorder rather than a language disorder. Following this, several theories and hypotheses were put forth by many researchers. In the ancient past, much importance was given to the cardio-centric view in which heart functioning is considered the most significant and brain functioning was almost neglected. It is believed that “good” and “evil” were often associated with the cardio-centric view [4]. The “Theory of fluids” which says that aphasia is caused by imbalance in the body fluids and some medical reports written thereby were some of the earliest traces of aphasia. Some old references to aphasia are tracked to the work done by Papyrus, Plato, Aristotle, Herophilos and Galen [4]. The work of these scientists attributed to the occurrence of “The Grecco-Roman period” which emphasised on linking the cognitive processing to some possible body structure. Some believes were that the ‘reasoning’ and ‘mind’ were localized to the head, higher characteristics like ‘pride’ and ‘courage’ were localised to the heart and lower characteristics like ‘lust’ and ‘desire’ were localised to the abdomen [4]. Following this, the “Ventricular Theory” which states that ‘psyche’ and the ventricles are connected and that ventricles are important for appropriate functioning in humans. The emergence of the “Renaissance” period in the 17th century marked the beginning of modern science and medicine, thereby, leading to tremendous increase in the study of anatomy and physiology and hence the descriptions of the characteristics of aphasia became clearer in this period. It is highlighted that the convolutions of the brain form the anatomical basis for the functions of memory and language [4]. As time passed by, the first real theory of aphasia described by Gesner as the ‘Language Amnesia’ took its mark in the history of aphasia. After which, one of the most influential theoretical framework was put forth by Gall (1806) [5], an anatomist. He proposed the concept of “organology” or “phrenology”, referring to localization of different areas of the brain and the numerous corresponding functions controlled by those anatomical sites. This trajectory seen in the history of aphasia led to several important studies which have played a significant role in shaping the present-day knowledge about the neuroscience related to aphasia.

Early studies in Aphasia and Lesion Localization

Paul Broca (1861) formulated the ‘Theory of Language Localization’ which states that language is controlled in the left hemisphere. This theory was supported by numerous reports of patients with ‘Aphemia’ which was caused by lesion in the third frontal gyrus, presently, known as the Broca’s area [6,7]. Damage to this anatomical site was shown to cause hesitant speech, effortful speech, and difficulty in syntax production, poor naming and repetition skills with relatively intact comprehension abilities [6]. Further, Trousseau (1864) [7] coined term ‘Aphasia’ (meaning speechlessness) instead of all the other terminologies. Therefore, patients described in the studies by Broca, were, later, noted to be diagnosed with Broca’s aphasia. Following this, Carl Wernicke (1874) reported two patients whose symptomatology and lesion localization were completely different from what was reported by Broca [8]. This led to the understanding about another type of aphasia, presently known as the Wernicke’s aphasia which was characterized by poor auditory comprehension, press of speech, logorrhoea, and poor naming and repetition skills [8]. These functional deficits were attributed to the lesion in the posterior portion of the superior temporal gyrus, which is now called as the Wernicke’s area [6].The two set of studies by Broca and Wernicke paved way for a debate about the need for classification of the aphasic syndromes.

Connectionism, Assosiationism and Neo-Associationism

Building a theoretical framework based on the clinical presentations reported by Broca and Wernicke, and other researchers, became the primary focus at that point. The most influential models that contributed to the theory of aphasia include ‘Psycholinguistic Model’ or ‘Wernicke’s Model’(describing aphasia from the site of lesion in Wernicke’s area and Broca’s area), ‘Wernicke-Lichtheim model’ (describing the different aphasia types based on the sight of lesion such as Broca’s aphasia, Wernicke’s aphasia, conduction aphasia, transcortical motor aphasia, transcortical sensory aphasia, subcortical motor aphasia and transcortical sensory aphasia), and ‘Wernicke-Geshwind model’ [9] (describing the functions of Wernicke’s area, arcuate fasiculus, Broca’s area, primary auditory cortex, primary visual cortex, primary motor cortex, and the angular gyrus). Several researchers actively contributed to the literature pertaining to aphasia, either by supporting (like, Jules Dejerine) or opposing (like, Pierre Marie) the need to classify aphasia [3, 10].

From this point of reference, the taxonomy of aphasia was put forth using several approaches. Some approaches include functional anatomical approach, physiological approach, psychopathological approach, neurolinguistic approach, Linguistic approach, psycholinguistic approach, and psychological approach. Later in the 18th century, the era of ‘Diagram makers’ or the ‘connectionists’ evolved, supremely explaining how the different brain areas are responsible for specific functions and how these areas are connected amongst each other (Rose et al., 1988). The novelty marker of ‘Connectionism’ is that it is a combination from the concepts derived from ‘phrenologists’ (who consider localization and specific anatomical sites) and ‘Associationists’ (who consider the connections between the anatomical sites). Based on ‘Connectionism’, Wernicke classified aphasia into subcortical sensory aphasia (lesion in connections between the primary auditory cortex and surrounding areas) , cortical sensory aphasia (lesion in association cortex), subcortical motor aphasia (lesion in connections between the primary motor cortex and Broca’s motor language center), cortical motor aphasia (lesion in Broca’s motor language center), conduction aphasia (lesion in acruate fasciculus), transcortical aphasia (lesion in the sensory and motor language centers and cortical areas) [1,12].

Towards the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, the Modern Connectionism or Neo-Associationism took the limelight. The extensions of the classical connectionism was started mainly by Wernicke and Lichtheim [1]. The work done in the consideration with Neo-associationism focused specific language functions like naming, spontaneous speech production, and repetition. A major contribution of the neo-associationism was that the idea gave rise to the concept of ‘Disconnection syndromes’, ‘Alexia’, ‘Agraphia’ and ‘Aprosodia’ which occurs in case of disruption in connection fibers, angular gyrus, supramarginal gyrus and language areas of the right hemisphere respectively [9].

Holism and Hierarchical / Evolution based models

The Holistic models emphasize on the layered or hierarchical structure of the brain which is arranged from simple, lower and primitive level of tissue structure and functioning to the later developed, complex, higher level of brain areas and its corresponding functioning. Two main models to consider in this topic of consideration put forth by Jackson and Brown, respectively [4].

Jackson described two levels of language based on Spencer’s evolutionary principles, which are, automatic and propositional levels. The automatic level of speech production consists of highly routinized stereotyped utterances which do not require active involvement of the higher structures. While the propositional level is defined as the one which requires accurate planning for semantics, syntax and other linguistic components before it is produced, therefore, requiring the involvement of higher brain structures. Therefore, the propositional speech is considered as a part of ‘thinking’. So, Jackson describes Aphasia as an inability to ‘propositionalize’ the linguistic utterances. This point of view does not emphasis much on the neural substrates to speech and language.

Brown’s Microgenetic theory of language-brain relationship views language as a system which has several levels of specific symbols. Two levels of speech production are discussed through this chapter, namely, anterior pathway and posterior pathway. There are four levels of representations (i.e, Bilateral limbic cortex, limbic or generalized neocortex, generalized or focal neocortex and focal neocortex) described under anterior pathway and four syndromes (i.e, Akinetic mutism, transcortical motor aphasia, agrammatism, broca’s aphasia) that occurs correspondingly are described. Likewise, the posterior pathway is described using three levels of representation (i.e, Limbic and limbic-derived cortex, generalized neocortex and focal neocortex) with the corresponding deficits (i.e, Asemantic- associative, categorical-evocative, and phonological) that could occur due to damage to these levels.

Process models and Luria’s Classification

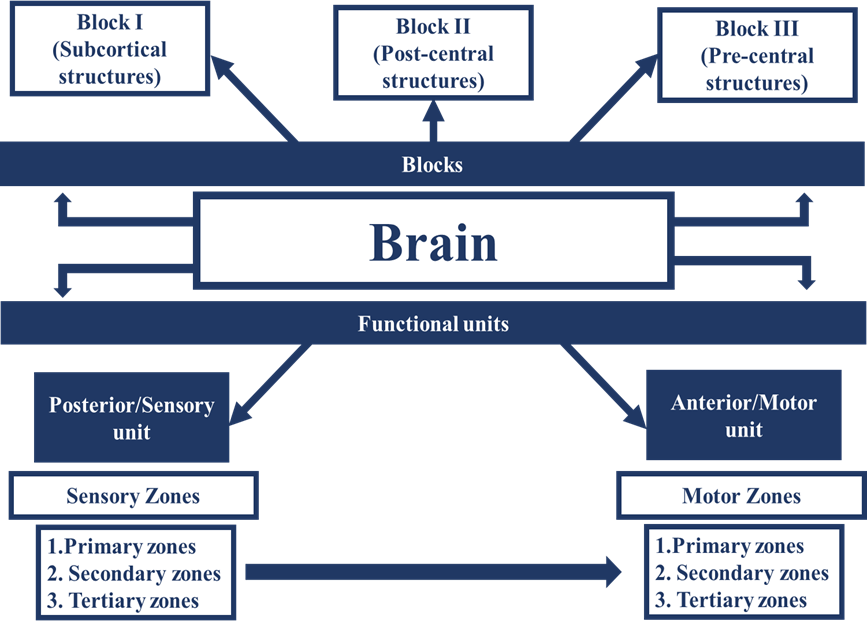

Models that fall in this domain mainly throw light on the important ‘processing components’ or ‘language faculties’ required for verbal communication. This provides insight about how these processing components come together to produce the final verbal output. These processes include speech comprehension, speech production, naming, reading, writing and memory. From this point of view, it can be stated that Luria’s process model has been the most influential in aphasiology [13]. This model divides the cortex into two functional units: a. Posterior portion or the sensory unit which receives and processes sensory information and b.Anterior portion or the motor unit which formulates intentions and organizes the actions to execute it for speech production. In each of the functional units, information flows in the primary, secondary and tertiary zones, although the flow of information is in the opposite direction in both the functional units (ie, the information flows from primary to secondary and finally to tertiary zones in the sensory unit, but in the motor unit, it the tertiary unit which receives information from sensory unit, this information processed by the secondary followed by the primary zones) [10]

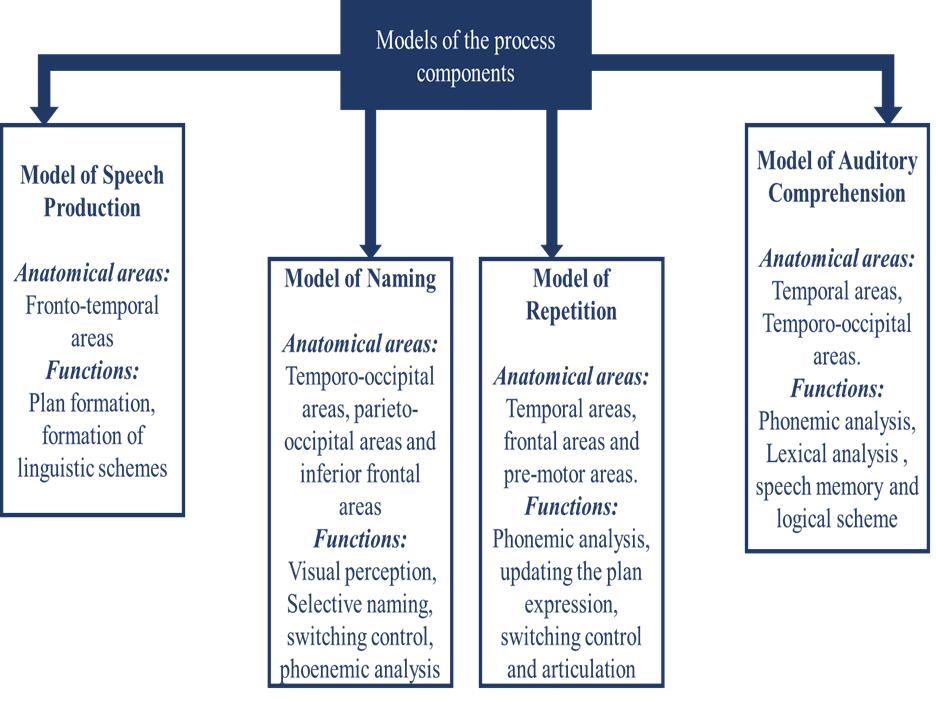

In order to account for the contributions from different brain regions, the brain is divided into three blocks according to the Luria’s model. Block I, II, and III consists of the subcortical structures, post-central cortex (consisting of secondary sensory zone, and medial zones in temporal lobe) and pre-central cortex (motor tertiary and secondary zones) respectively [13]. The blocks, zones and the functional units from Luria’s model are represented in Figure 1 below. The theory structured by Luria was delineated using separate models for each of the ‘processing components’, that is, models for auditory comprehension, naming, repetition and speech production. The anatomical structures and functions occurring for each process component are depicted in the Figure 2.

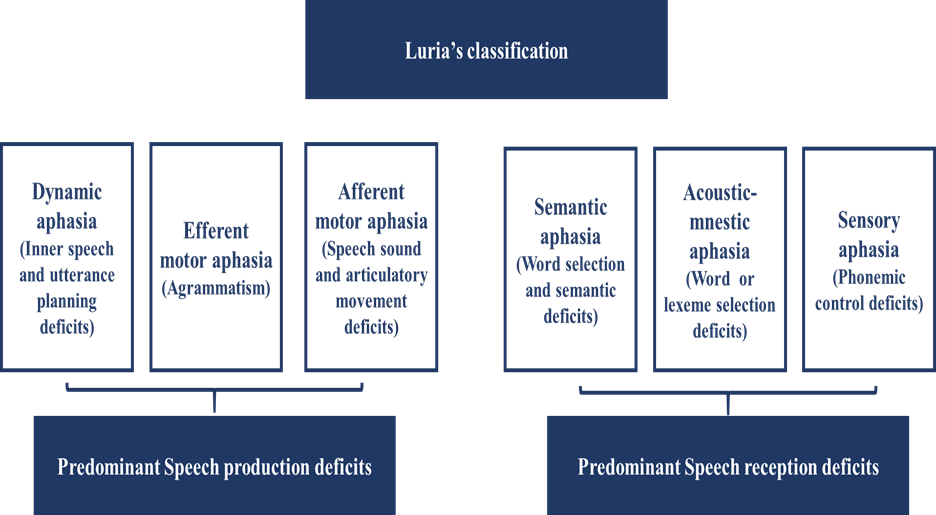

Based this process model and the work done by Vygotsky, a classification different from the Boston group of classification was proposed by Luria [13]. This classification system took the dynamic and evolutionary approaches into consideration by bringing the concept of ‘Higher mental functions’ into the spotlight. The rationale for this classification is based on three principles, namely, ‘Principle of social genesis’ (which says that cultural development occurs in external social and internal psychological planes), ‘Principle of Systemic structure’ (which describes the importance of highly differentiated brain structures for performing higher mental functions) and ‘Principle of dynamic organisation and localisation’ (which describes that there are changes in the structures and its localizations because of structural ontogenesis, changes in level of automatization and variability in performing the same results using different information processing strategies) [13]. In Luria’s aphasia classification, there are six types of aphasia predominantly. The following flowchart given in Figure 3 depicts the different types of aphasia along with its key clinical symptomatology.

Figure 1: Blocks, Functional units and Zones described in Luria’s model

Figure 2: Models of the ‘processing components’

Figure 3: Types of Aphasia and their symptomatology based on Luria’s classification

Summary flow chart for the concept of aphasia

Recent classification of Aphasia

Many other attempts to classify aphasia have resulted in differences in the taxonomy of the disorder. Some classification systems which have left their mark in the history of aphasia include the Wernicke’s classification, Boston group classification, Head’s classification, Luria’s classification, and Benson and Ardilla’s classification [12]. All of these systems have considered different approaches to provide the demarcation between the subtypes of aphasia. Taking all the aspects into account, the most recent attempt to reinterpret the taxonomy of aphasia was discussed by Ardilla [12]. The reclassification is strongly justified because of the need to incorporate the information that we can obtain using the advancing neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, single photon emission computer tomography and tractography [14]. Ardilla [12] discussed two major aphasic syndromes

(Broca’s type and Wernicke’s type) related to two basic language operations (language as paradigm and language as a syntagm). A person with aphasia could either have impairment in the paradigmatic axis (similarity disorder corresponding to Wernicke’s type of aphasia) or syntagmatic axis (continuity disorder corresponding to Broca’s type of aphasia). The similarity disorder is characterised by difficulties in recognition of phoneme, lexicon and semantic aspects, whereas the lack of fluency, disintegration of speech movements, apraxia, agrammatism and syntactic aspects are corresponding to continuity disorder. Other secondary types of aphasia including transcortical sensory aphasia, transcortical motor aphasia or dysexcecutive aphasia, conduction aphasia, supplementary motor area, and subcortical aphasia.

Conclusion

Several compensatory rehabilitative approaches and care-giver counselling strategies also vary depending on the type of aphasia. Although the some of the above-mentioned points emphasizes on the need to classify aphasia, the inability to define individual characteristics and design unique treatment repertoire specific to persons with aphasia is a major downside to classification of aphasia. The debate about whether or not to classify the aphasic syndrome remains blurred in concept, however, there is clarity about the need to consider all aspects about the patient, in and out of the purview of classification, to bring the essence of a complete clinical profile of the patient and to work towards the utmost functional betterment in persons with aphasia.

References

- Damasio, A. R. (1992). Aphasia. New England Journal of Medicine, 326(8), 531-539.

- Marx, O. M. (1967). Freud and aphasia: an historical analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 124(6), 815-825.

- Kasselimis, D. S., Simos, P. G., Peppas, C., Evdokimidis, I., & Potagas, C. (2017). The unbridged gap between clinical diagnosis and contemporary research on aphasia: A short discussion on the validity and clinical utility of taxonomic categories. Brain and language, 164, 63-67.

- Prins, R., & Bastiaanse, R. (2006). The early history of aphasiology: From the Egyptian surgeons (c. 1700 bc) to Broca. Aphasiology, 20(8), 762-791.

- Gall, F. J. (1806). Herinneringen uit de lessen van Frans Joseph Gall, Med. Doctor te Weenen, over de hersenen als onderscheidene en bepaalde werktuigen van den Geest, gehouden te Amsterdam, van den 8sten tot den 13den van de Grasmaand 1806, opgeteekend door zijnen toehoorder M. Stuart.

- Eling, P., & Whitaker, H. (2022). History of aphasia: A broad overview. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 185, 3-24.

- Trousseau, A. (1865). Clinique médicale de l'Hôtel-Dieu de Paris (Vol. 2). Baillière.

- Joynt, R. J., & Benton, A. L. (1964). The memoir of Marc Dax on aphasia. Neurology, 14(9), 851-851.

- Geschwind, N., & Geschwind, N. (1974). Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man (pp. 105-236). Springer Netherlands.

- Boller, F. (2006). Modern neuropsychology in France: Henry Hécaen (1912-1983) and the Sainte-Anne Hospital. Cortex, 8(42), 1061-1063.

- Moskowitz, H. R., Ermelando, V., Cosmi, E. V., Costa, N. D. R., Costa, O. T., Costa, P. T., ... & Costa, F. A. (1990). 02NLM: GG7106 OXNLM: [WA 11 DB8]. National Library of Medicine Current Catalog: Cumulative listing, 2, 182.

- Ardila, A. (2010). A proposed reinterpretation and reclassification of aphasic syndromes. Aphasiology, 24(3), 363-394.

- Akhutina, T. (2016). Luria’s classification of aphasias and its theoretical basis. Aphasiology, 30(8), 878-897.

- Tippett, D. C., Niparko, J. K., & Hillis, A. E. (2014). Aphasia: Current concepts in theory and practice. Journal of neurology & translational neuroscience, 2(1), 1042.