Archive : Article / Volume 2, Issue 1

Case Report | DOI: https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-8851/009

Exploratory Model of Collaboration Networks in the COVID-19 Era

1 Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México

2 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Correspondng Author: Cruz Garcia-Lirios

Citation: Cruz Garcia-Lirios, Miguel Bautista Miranda, Javier Carreón Guillén, (2023). Exploratory Model of Collaboration Networks in the COVID-19 Era. Neurons and Neurological Disorders. 2(1). DOI:10.58489/2836-8851/009

Copyright: © 2023 Cruz Garcia-Lirios, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received Date: 2023-02-11, Received Date: 2023-02-11, Published Date: 2023-03-03

Abstract Keywords: culture; institutionalism; leadership; network; collaboration

Abstract

knowledge networks and organizational collaboration reflect a culture of success, transformational leadership and a climate of relationships around which relationships of trust, support, innovation and goals are generated. These are bi-directional and horizontal organizations with equity and solidarity. The objective of the present study is to establish the correlations between the factors, a non-experimental, transversal and exploratory study was carried out with a selection of 300 administrative staff, students and teachers from a public university in central Mexico. to structural model. The results show that there is a dependence relationship between goal climate and collaboration. Based on these findings, research lines related to trust as a determinant of knowledge networks and organizational collaboration are noted.

Introduction

The objective of this work was to specify a model for the study of collaboration networks by establishing the reliability and validity of an instrument that measures the organizational process in a sample of administrators, teachers and students of a Higher Education Institution of the State of Mexico affiliated with the National Association of Faculties and Schools of Accounting and Administration (ANFECA).

In the context of educational policies focused on the link between the local market and academic curricula, social entrepreneurship through academic networks involves the formation of a gender identity or habitus which consists of the professional training of an ethic of collaboration (Cruz et al., 2016). It is an ethic that begins with the establishment of empathy, trust, commitment, innovation, satisfaction and happiness (García et al., 2016).

In this way, collaborative networks, derived from educational institutionalism consisting of the evaluation, accreditation and certification of the quality of processes and products, show the differences between genders based on their abilities, skills and knowledge (Hernández & Valencia, 2016).

Therefore, the formation of collaborative networks supposes the training or training of groups around specific objectives, tasks and goals, but the formation of collaborative networks around professional identity supposes the establishment of a system of communication and motivation of the leader. towards the talents or among the employees (Acar & Acar, 2014).

Collaborative networks are created around work environments such as relationships, tasks, support and innovation in order to be able to undertake or specify knowledge that will result in innovation depending on the degree of complexity relative to self-regulation, dissipation, adaptability and dynamism (see table 1).

Table 1. Structures and climates in complex organizations

| Rules | Support for | Innovation | Goals |

Self-regulation | Self-regulated organizations set standards in order to strike a balance between external demands and the availability of internal resources. | Self-regulated organizations establish forms of cooperation and solidarity in the face of a significant difference between opportunities and capabilities. | Self-regulated organizations produce knowledge and innovations in order to restore a balance between risks and objectives, uncertainty and goals. | Self-regulated organizations determine objectives and goals based on the balance of their expectations and needs. |

Dissipation | Emerging organizations are guided by principles of restructuring based on the availability of resources rather than market demands. | Emerging organizations relate to knowledge-producing nodes to generate opportunity structures in situations of unemployment. | Emerging organizations reflect the uncertainty of economic crises and their innovations are an effective response to uncertainty and entrepreneurial risks. | Emerging organizations determine objectives and goals as market demands are contingent. |

Adaptation | Adaptive organizations follow unpredictable principles from which they structure new opportunities and capabilities. | Adaptive organizations underlie the uncertainty of the markets in order to structure new collective knowledge. | Adaptive organizations generate information leading to new insights and innovations to deal with market instability. | Adaptive organizations establish objectives and goals based on the risks involved in entrepreneurship and innovation. |

Dynamic | Dynamic organizations are unstable before the development of their quality processes. | Dynamic organizations through cooperation and solidarity establish the quality of their processes and products. | Dynamic organizations are flexible in the face of market instability and State demands. | Dynamic organizations set objectives and goals based on economic, political and social changes. |

Complexity | Complex organizations generate knowledge networks from which they establish imbalances and stability. | Complex organizations establish strategic alliances in order to produce value in terms of opportunities and capabilities. | Complex organizations generate innovations for positioning and local transformation. | Complex organizations establish their objectives and goals based on the contingencies of the environment. |

Source: Own elaboration, adapted from Carreón (2016)

At their core, complex organizations are collaborative. In other words, its relationship with the demands of its environment guides it towards self-regulation or the balance of its processes by optimizing its resources or innovating its capabilities based on the availability of opportunities. This is the case of organizations with a climate of collaborative relationships focused on rules (Mendoza, Ramírez and Atriano, 2016).

For their part, dissipative organizations generate collaborative networks to amplify their solidarity options or support climates based on their future possibilities. In the same sense, the theory of prospective decisions warns that dissipative organizations are those that direct their collaborative networks towards scenarios that pose more risks than benefits if the latter are minimal (Omotayo and Adenike, 2013).

In contrast, the theory of prospective decisions indicates that adaptive organizations are those that orient their collaborative networks towards unlikely profit scenarios with respect to minimal risks or threats (Escobar, 2014).

This is how dynamic organizations, following the approaches of the theory of prospective decisions, are creators of innovations and diffusions according to work environments. In this sense, the production of knowledge is the result of a collaborative climate guided by intentions of maximizing benefits and reducing imponderables (Anicijevic, 2013).

Complex organizations develop collaborative networks for resource optimization and process innovation, since their relationship with their environment forces them to develop sustainability protocols focused on austerity, anticipation, altruism, effectiveness, deliberation and savings. of resources based on the scarcity of opportunities or the increase in external demands (see table 2).

Table 2. Temporary arrangements of complex organizations

| Austerity | Anticipation | Altruism | Effectiveness | Deliberation | Saving |

Self-regulation | √ | √ |

| √ | √ | √ |

Dissipation |

|

|

| √ | √ |

|

Adaptation | √ |

| √ | √ | √ | √ |

Dynamic |

| √ |

| √ | √ |

|

Complexity | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Source: Own elaboration, adapted from Carreón (2016)

In other words, complex organizations with collaborative networks are essentially sustainable since they develop an identity of propensity for the future, or rather, an identity of optimization of resources rather than innovation of processes (Quintero et al., 2016).

The orientation towards sustainability or the affinity towards the conservation of resources distinguishes complex organizations with collaborative networks focused on the optimization of resources (Sales, Quintero and Velázquez, 2016). The same propensity for a shared future not only implies that organizations assume resources as common goods, but also generates an isomorphic process in which they circumscribe themselves to guarantee their preservation through collaboration (Robles et al., 2016).

In this tenor of orientation towards sustainability, organizations are structured in networks, neurons, graphs, nodes or arcs to establish cooperative, supportive or collaborative relationships based on the contingencies of the environment (Vázquez et al., 2016) .

More precisely, organizations are built from values and norms that will determine the processing of information and based on this, they will make decisions and actions in relation to their increasingly scarce environment in terms of resources and opportunities. Therefore, sustainability-oriented organizations must optimize their resources, generating their own opportunities for a common future (Saansongu & Ngutor, 2012).

In the field of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), collaborative networks have emerged from cognitive psychology, mainly approached from the theory of technology adoption, self-efficacy and risk in general and computational self-efficacy and risk. informative in particular (Dugloborskyte & Petraite , 2017) .

In each of these three approaches, collaborative networks are the product of individual teaching and learning skills. The theoretical perspectives even allude to self-education, avoiding the relationships of power and influence proposed by social psychology (Storga , Mostahari , & Stankovic , 2013) .

In this way, in the face of individual skills, experiments emerge that will reliably demonstrate the social influence of collaborative groups in the retention, use and performance of individuals assigned to collaborative groups in the framework of work environments focused on task relations, innovations and supports. (Huilan, Liu & Onderati , 2017) .

Simpson (2008) reviewed the literature on collaborative distance learning to note a prevalence of group influence versus learning in its directed or self-taught modalities. The difference is that the collaborative groups strengthened their retention capacity more than those individuals trained from the motivation of their abilities or the self-motivation of their abilities. That is to say, while the transfer of knowledge was carried out based on the use and processing of information that the teacher had to correct and adjust to a line of learning, empathic and synergistic relationships were established in the collaborative groups that potentiated their capacities and abilities. retention, learning, achievement and performance.

However, both learning routes, that of individual competencies with respect to social influence, oscillate between tacit knowledge and implicit knowledge deposited in the talents and leaders that the organization must retain in order not to lose that intellectual capital and also make concessions to these carriers of knowledge so that they can transfer their skills or strategies to future generations of educators and students (García, Soto & Miranda, 2017).

This is how knowledge management arises to protect the accumulation of information that only talents and leaders can capitalize on in favor of the organization. In this sense, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), electronic devices and digital networks become relevant in the construction of intangible assets and competitive advantages for organizations dedicated to the creation of knowledge, mainly those that produce it, such as case of HEIs in general and public universities in particular (Wu, Tuo and Xiong, 2015).

Knowledge management, in a computational sense, supposes the codification of implicit knowledge to tacit knowledge, as would be the case of decisions and actions based on the iteration of opportunities and challenges (Jabar, Sidi and Selamar, 2010)

Regarding knowledge management, the models revolve around the capacities, skills and individual abilities, therefore, most of them in the implicit order with respect to the more tacit models and therefore more empathic, communicative and tacit as This is the case of the synergistic model of knowledge networks.

In this way, between the synergistic model of social influence mediated by some technology and the model of competencies and vertical transfer, broadly speaking , the intermediate model of knowledge management or conversion and protection of information resulting from experience and individual skills It includes three phases: 1) knowledge capture processing through the conceptual mapping of information from knowledge agents and receiving agents; 2) construction and management of user profiles, skills and knowledge networks; 3) generation of knowledge structures for the group knowledge repository (García, 2013).

However, in this knowledge management approach, unidirectional and therefore unilateral communication and motivation prevail. That is, knowledge is managed, produced and transferred in a vertical sense without considering the needs of users or their possibilities of interaction of utility expectations.

Therefore, it is necessary to delve into the interior of a network of academic knowledge with a collaborative sense, which can be observed in its levels of relationships, innovations, supports and goals according to the contingencies of its environment, as is the case of a system of practices and social service implemented between the public university and branches of an automotive multinational in central Mexico.

In the context of the strategic alliance between the HEI and the multinational, the internship and social service systems emerge as a scenario for the study of collaborative networks derived from the management, production and transfer of knowledge, but because such an alliance is oriented towards the labor insertion of the student, therefore, it will be necessary to observe its dimensions of supports, innovations, goals and relationships.

Will the organizational dimensions oriented to the complexity of their collaborative and sustainable processes put forward in the consulted literature adjust to the empirical observations to be made in a case study with students, administrators and teachers of a public university in central Mexico?

Organizations dedicated to Knowledge creation through collaborative networks develops and consolidates dimensions of complexity related to self-regulation, dissipation, adaptability and dynamism as a hallmark of resource optimization and process innovation. In this sense, it is possible to observe such dimensions in a case study with a HEI in central Mexico. Despite the fact that the theories and empirical findings reviewed in the literature warn that organizations develop complex collaborative networks in order to self-regulate, dissipate, adapt and become more dynamic in the face of resource scarcity, the specificities of the context and the particularities of the sample. of study warn that it is an unprecedented phenomenon and therefore explorable in terms of its organizational structures.

Method

A non-experimental, cross-sectional and exploratory study was carried out. A non-probabilistic selection of 300 administrators, teachers and students from a public university affiliated with ANFECA in area five was carried out.

The Carreón Organizational Collaboration Scale (2016) was used, which includes four dimensions related to the climate of relationships, support, innovations and goals. Each item is answered with one of five options ranging from “not at all in agreement” to strongly in agreement”.

The Delphi technique was used for the homogenization of the words included in the statements of the instrument. The confidentiality of the results was guaranteed in writing and it was reported that they would not negatively or positively affect their work-administrative status. The information was processed in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Mean, standard deviation, alpha, sphericity, adequacy, factor weights, goodness of fit, and residuals were estimated.

Results

Table 3 shows the statistical properties of the instrument that established four dimensions of organizational collaboration, namely: the climate of relationships, support, innovations and goals with Crombach 's alpha coefficients higher than the indispensable minimum (0.700) to consider it as a consistent measurement.

Table 3. Instrument Descriptives

| R | Item | M | D | yes | C | A | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 |

| subscale (specifications before generalities) | 0.781 | |||||||||

| r1 | Educational evaluation generates indexed articles | 3.24 | 1.25 | 1.02 | 1.32 | 0.743 | 0.632 | |||

| r2 | The production of innovations is consistent with educational quality | 3.29 | 1.27 | 1.39 | 1.35 | 0.793 | 0.694 | |||

| r3 | Thesis advisory derives from the merit contest | 3.00 | 1.47 | 1.40 | 1.38 | 0.714 | 0.661 | |||

| r4 | Research projects arise from credentialism | 4.28 | 1.85 | 1.44 | 1.54 | 0.756 | 0.632 | |||

| subscale (collaboration in the face of imponderables) | 0.793 | |||||||||

| r5 | Mass education meant the weakening of trade unionism | 3.05 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.47 | 0.742 | 0.631 | |||

| r6 | Teacher individualism obeys educational policies | 3.81 | 1.37 | 1.28 | 1.39 | 0.746 | 0.635 | |||

| r7 | Educational neoliberalism generates collegiate jobs | 3.21 | 1.21 | 1.38 | 1.27 | 0.784 | 0.563 | |||

| r8 | Multidisciplinary research is a product of meritocracy | 3.56 | 2.31 | 1.29 | 1.07 | 0.795 | 0.594 | |||

| subscale (proposals for contingencies) | 0.785 | |||||||||

| r9 | Teaching proposals underlie the educational crisis | 4.21 | 1.70 | 1.33 | 1.21 | 0.790 | 0.671 | |||

| r10 | Educational desertion generated the scholarship system | 4.24 | 1.48 | 1.20 | 1.24 | 0.712 | 0.493 | |||

| r11 | Constructionism is the result of educational backwardness | 3.91 | 1.31 | 1.25 | 1.36 | 0.774 | 0.614 | |||

| r12 | Educational policies favored credentialism | 3.26 | 1.83 | 1.37 | 1.32 | 0.732 | 0.632 | |||

| subscale (achievements in the face of risks) | 0.758 | |||||||||

| r13 | Budget cuts caused absenteeism | 4.34 | 1.83 | 1.09 | 1.30 | 0.795 | 0.381 | |||

| r14 | Recognitions are derived from mass education | 4.65 | 1.57 | 1.15 | 1.26 | 0.782 | 0.532 | |||

| r15 | Multidisciplinary studies indicate the techno -scientific policy | 4.81 | 1.46 | 1.13 | 1.32 | 0.784 | 0.635 | |||

| r16 | Educational financing is achieved with the management | 4.30 | 1.24 | 1.36 | 1.49 | 0.793 | 0.512 |

M = Mean, D = Standard deviation, S = Bias, C = Kurtosis, A = Alpha minus the value of the item. Extraction method: Main components. Sphericity and adequacy ⌠χ2 = 3.251 (23df) p = 0.000; KMO = 0.681⌡. F1 = Climate of Relationships (45 of the total variance explained), F2 = Climate of Supports (15 of the total variance explained), F3 = Climate of Innovations (8 of the total variance explained), F3 = Climate of goals (3 of the total explained variance). All the items include the alpha value minus their estimation and include five response options: 0 = “I do not agree at all” to 5 = “I strongly agree”.

Once the four factors that explained 71 of the total explained variance were established, the relationships between the factors were estimated in order to establish the possible relationships of the factorial structure with respect to other variables not specified or estimated in the model.

M = Mean, D = Standard deviation, S = Bias, C = Kurtosis, A = Alpha minus the value of the item. Extraction method: Main components. Sphericity and adequacy ⌠χ2 = 3.251 (23df) p = 0.000; KMO = 0.681⌡. F1 = Climate of Relationships (45% of the total variance explained), F2 = Climate of Supports (15% of the total variance explained), F3 = Climate of Innovations (8% of the total variance explained), F3 = Climate of goals (3% of the total explained variance). All the items include the alpha value minus their estimation and include five response options: 0 = “I do not agree at all” to 5 = “I strongly agree”.

Once the four factors that explained 71% of the total explained variance were established, the relationships between the factors were estimated in order to establish the possible relationships of the factorial structure with respect to other variables not specified or estimated in the model.

Table 4. Relations between the factors and the construct

| Estimate | CR | P | ||||

| Relations | <--- | Collaboration | 0.50 | |||

| Props | <--- | Collaboration | -0.10 | ,586 | ,837 | .403 |

| Innovations | <--- | Collaboration | -0.17 | 2,679 | ,911 | .362 |

| Goals | <--- | Collaboration | -0.33 | .667 | -1,341 | ,180 |

Source: self-made.

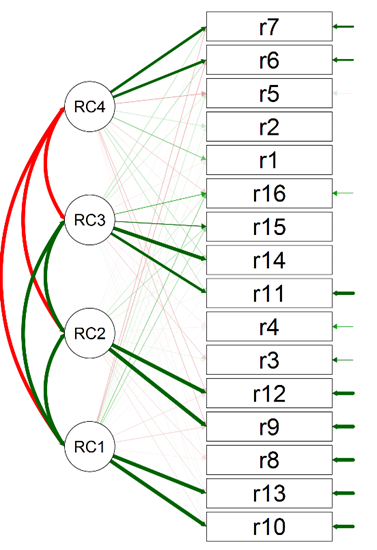

Once the relationships between the factors were established, the structural model was estimated (see Figure 1) in which the fit and residual parameters ⌠ χ 2 = 3.432 (2df) p = 0.180; GFI = 0.950; RMSEA=0.001; Bootsrap = 0.0000⌡ suggest the acceptance of the null hypothesis regarding the adjustment of the theoretical explanations with respect to the empirical observations made in the case study of the public university.

RCR = Collaborative Networks of Relationships, RCA = Collaborative Networks of Supports, RCI = Collaborative Networks of Innovations, RCM = Collaborative Networks of Goals

Discussion

The contribution of the present work to the state of the question lies in the specification of a model for the study of complex organizations with collaborative networks oriented towards sustainability, but the type of non-experimental study, the type of non-probabilistic sampling and the type of Exploratory factor analysis limits the findings to the study sample.

In relation to the studies of collaborative networks which highlight isomorphism and propensity for the future, the present work has shown that four dimensions relative to collaborative networks of relationships, supports, innovations and goals prevail, but the percentage of the total variance explained supposes the inclusion of other factors that the literature identifies as task climate and trust networks.

In other words, collaborative networks distinguish complex organizations from the contingencies of their environment, but it is the norms and values that stand out as indicators of organizations dedicated to the production of knowledge and the formation of intellectual capital in order to create intangible value in its processes.

In this way, the present work has evidenced the formation of collaborative networks from the climate of relationships to the climate of goals, which suggests that: 1) in complex organizations focused on self-regulation, collaborative networks build objectives, tasks and goals with based on the balance of external demands and its internal resources; 2) in sustainable organizations, collaborative networks serve as dissipators of knowledge to increase the formation of intellectual capital; 3) in knowledge-producing organizations, adaptability is an instance that will come to generate more knowledge in order to conserve the organization itself and its resources; 4) Organizations that optimize their resources form collaborative networks to activate a dynamic of exchanges and transactions with their contingent environment.

Therefore, it is necessary to carry out the contrast of the specified model in contexts and samples similar to the HEI under study, as well as the inclusion of a fifth factor to increase the percentage of explained variance and guide the model towards the formation of dedicated intellectual capital. to the optimization of resources and the innovation of processes.

In this way, the inclusion of the climate of empathic relationships or trust in the model will allow us to observe its link with the formation of academic and professional networks in a system of professional practices within the framework of strategic alliances between HEIs and multinationals.

In other words, the construction of an ethic of preservation and collaboration or a climate of empathic and trusting relationships between students, teachers and administrators supposes the beginning of a selective process of information that, when decoded, will allow the protection of implicit knowledge in some technology. in order to enhance the capabilities, skills and abilities of future users in increasingly risky, contingent and threatening scenarios.

This is so because the transfer of implicit knowledge in tacit knowledge is generated from a work environment focused on empathy and trust rather than on competence. Consequently, a knowledge management model implies the inclusion and measurement of the level of trust and empathy of an organization, as well as its competencies based on the demands of the environment and the opportunities of the context.

Such a model would include: 1) knowledge management based on a diagnosis of the level of empathy and trust; 2) knowledge production based on common objectives, tasks and goals between HEIs and multinationals; 3) transfer of knowledge through the internship system and social service, as well as the academic, technological and professional training of intangible assets such as intellectual capital.

Conclusion

The objective of this work has been to specify a model for the study of complex organizations with collaborative networks that optimize resources and innovate processes in the face of contingencies in their environment, but the type of study, sample and analysis limits the model to the study sample, although it suggests its contrast in other scenarios. It is a model from which it will be possible to form collaborative groups based on the construction of an identity or propensity for a shared future.

References

- Acar, Z., and Acar, P. (2014). Organizational culture types and their effects on organizational performance in Turkish hospitals. Emerging Markets Journal, 3(3), 1-15. DOI: 10.5195/emaj.2014.47

- Anicijevic, N. (2013). The mutual impact of organizational culture and structure. Economy Annals, 58 (198), 35-60

- Carreon, J. (2016). Human Development: Governance and Social Entrepreneurship. Mexico: UNAM-ENTS

- Cruz, O., Arroyo, P., and Marmolejo, J. (2016). Technological innovations in logistics: inventory management, information systems and outsourcing of operations. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 165-178). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Dugloborskyte, V., & Petraite, M. (2017). Framework for explaining the formation of knowledge intensive entrepreneurial born global firm: Entrepreneurial, strategic and network-based constituents. Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business, 2(1), 174-202. DOI: 10.1344/jesb2017.1. j026

- Escobar, R. (2014). Neural networks, cognitive processes and behavior analysis. International Journal of Behaviorism, 2 (1), 23-43

- Garcia, C. (2013). The knowledge network in a university with a system of professional practices and administrative technological social service. Foundations in Humanities, 14(27), 135-157

- García, C., Carreón, J., Hernández, J and Salinas, R. (2016). Governance of the actors and networks of technological innovation. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 79-94). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Garcia, C., Soto, ML, and Miranda, M. (2017). Knowledge networks around coffee growing in a HEI in central Mexico. Interconnecting Knowledge, 2(4), 15-32.

- Hernandez, A., and Valencia, R. (2016). Innovation instruments: social networks in the internalization of micro, small and medium-sized Mexican companies. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 47-66). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Huilan, C., & Liu, S., & Onderati, F. (2017). A knowledge network and mobilization framework for lean supply chain decision in agri -food industry. International Journal of Decision Support System Technology, 9(4), 1-15 DOI: 10.4018/IJDSST.2017100103

- Jabar, M., Sidi, F., & Selamar, H. (2010). Tacit knowledge codification. Journal of Computer Science, 6(10), 1141-1147

- Mendoza, E., Ramírez, L., & Atriano, R. (2016). Use of media and technologies in the creation of an innovation system for the common good. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 95-114). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Nielsen, B. (2002). Synergies in strategies alliances: Motivations and outcomes of complementary and synergistic knowledge networks. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 43, 1-10

- Omotayo, O., & Adenike, A., (2013). Impact of organizational culture on human resource practices: a study of selected Nigerian private universities. Journal of Competitiveness, 5 (4), 115-133. DOI: 10.7441/joc.2013.04.07

- Quintero, M., Velázquez, E., Sales, J., and Padilla, S. (2016). A review of the state of the art on SMEs. What about innovation studies? In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 31-43). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Robles, C., Alviter, L., Ortega, A., & Martínez, E. (2016). Culture of quality and innovation in microenterprises. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 11-30). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Saansongu, E., & Ngutor, D. (2012). The influence of corporate culture of employee commitment to the organization. International Journal of Business and Management, 7 (22), 1-8

- Sales, J., Quintero, M., and Velázquez, E. (2016). Adaptation versus innovation: the formation of industrial districts from peasant communities. Santa Cruz Atizapan and Chiconcuac. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 181-199). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Simpson, O. (2008). Motivating learners in open and distance learning: Do we need a new theory of learner support? Open learning, 23 (3), 159-170

- Storga, M., Mostahari, A., & Stankovic, T. (2013). Visualization of the organization knowledge structure evolution. Journal of Knowledge Management, 17 (5), 24-40 DOI: 10.1108/JKM-02-2013-0058

- Vázquez, C., Barrientos, B., Quintero, M., & Velázquez, E. (2016). Government support for innovation, technology and training for small and medium-sized companies in Mexico. In M, Quintero., Sales, J. and Velázquez, E. (Coord.). Innovation and technology challenges for its practical application in companies, (pp. 67-78). Mexico: Miguel Ángel Porrúa -Uaemex.

- Wu, S., Tuo, M., & Xiong, D. (2015). Network structure detection of analysis and Shanghai stock market. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management, 8 (2), 383-398 DOI: 10.3916/jiem.1314