Research Article | DOI: https://doi.org/10.58489/2836-5933/003

Marine Litter in The Perception of a Group of Fishermen

1. Department of Sciences, Faculty of Teacher Training, State University of Rio de Janeiro, São Gonçalo, RJ, Brazil.

*Corresponding Author: Fábio Vieira de Araujo

Citation: Fernanda Braga da Silva Vasconcelos, Fábio Vieira de Araujo, (2023). Marine Litter in The Perception of a Group of Fishermen. Journal of Marine Science and Research. 2(1). DOI: 10.58489/2836-5933/003

Copyright: © 2023 Fábio Vieira de Araujo, this is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 01 February 2023 | Accepted: 06 February 2023 | Published: 09 February 2023

Keywords: environmental education; fishermen perception; ghost fishing

Abstract

Marine litter is a serious environmental problem and directly affects fishing activities. Otherwise, these activities contribute to the increase of marine litter with the abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), causing what is known as ghost fishing, responsible for the death of thousands of animals in marine environments. So, the present study sought to assess the profile and the perception about marine litter of fishermen from the Z7 colony, on Itaipu beach, an oceanic region of Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The evaluation was carried out through the application of an open questionnaire to 30 fishermen. The results indicated that despite observing the increasing pollution on marine environments and identifying the main pollutant, most of the interviewees only identify the impacts of the marine litter on their own work (fishing), without pointing the environmental concern as a whole, exempting themselves from guilt regarding the responsibility for this pollution found in the marine environment. Thus, the need for environmental education activities and other actions with this fishing community is evident, in order to mitigate the impacts of this pollution on marine environments.

Introduction

Despite its immense importance, the oceans have been used for years as a final reservoir of diverse types of wastes, such as chemicals, radioactive products, sanitary wastes and various types of solid waste such as plastic, glass, and metal (Blair et al., 2017).

The accumulation of garbage, especially plastics, has generated several environmental problems and raised concerns for scientists, researchers, government, NGOs, media and environmentalists around the world. Its presence in marine and coastal regions generates great damages for marine fauna, such as ingestion, entanglement and asphyxiation of more than 700 marine species (Gall & Thompson, 2015) and to the economy as the decreased in tourism (Werner et al., 2016). The fishing sector is directly affected by this pollution, with consequences in the reduction of fish and damage to fishing vessels (Laist, 1987; Orlandi et al., 2015).

Also, fishing activity has a major impact on the marine environment, either directly through overfishing or indirectly through abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), which, once free in the marine environment, end up causing the mortality of non-target species both in the substrate and in the water column in a process known as ghost fishing (Kowalski and Jenkins, 2021). Every year, an estimated 640,000 tonnes of ghost gear enter the world’s oceans, with significant impacts on marine life (WAP, 2022).

The loses of fishing artefacts can also keep releasing microplastics into the sea, that can be ingested by a variety of marine animals in all trophic levels and life stages (including larvae, juvenile, and adults), with ecological and economic damages (Burns and Boxall, 2018). The concern becomes even greater, since fishing equipment is increasingly more durable, increasing its lifetime in the marine environment (Matsuoka et al., 2005). According to Link et al (2019) the presence of ALDFG in Brazil was reported in 12 of the 17 coastal states and Schneider (2009) revealed that this problem is more linked to the negligence of fishing professionals than to accidental loss of equipment.

According to Pahl et al. (2017) and Zappes et al. (2016), the mitigation of marine litter requires an understanding of its ecological, social and economic impact and, in this sense, knowing the environmental perception of communities that use the marine environment is essential to understand the interrelationships between these and the marine environment, its expectations, anxieties, satisfactions and dissatisfactions, judgments and behaviors, seeking solutions for the conservation of these environments.

Among the different communities that make use of the marine environment, traditional fishing communities stand out. Several studies related to the perception of marine litter take into account bathers and traders (Tudor and Williams, 2003; Timbó et al., 2019), but few involve fishermen. A traditional artesanal fishing community is the one on Itaipu beach, Niterói, RJ (Pinto, 2010). This colony, founded in 1921, currently has around 170 fishermen and is part of the Z7 colony, which covers the beaches of Itaipu, Piratininga, Camboinhas, Itacoatiara, Itaipuaçu, Maricá, Ponta Negra and Jaconé in Saquarema and has around 785 registered fishermen (ATribunaRJ, 2020). On this same beach, Timbó et al (2019) worked on the perception of residents, bathers and merchants about litter on the beach and Castro et al (2020) and Silva et al (2015) studied microplastics and solid waste, respectively, finding large amounts in sand, water and sediments. The Aruanã project, which works with sea turtles in the region, has already found several dead individuals containing litter, including fishing gear in their digestive tract (personal communication).

Thus, this study aimed to investigate the perception of fishermen in relation to marine litter on Itaipu beach - Niterói (RJ), Brazil, beach that suffers from this problem; as a contribution to possible public measures against this problem, mainly related to ALDFG.

Methods

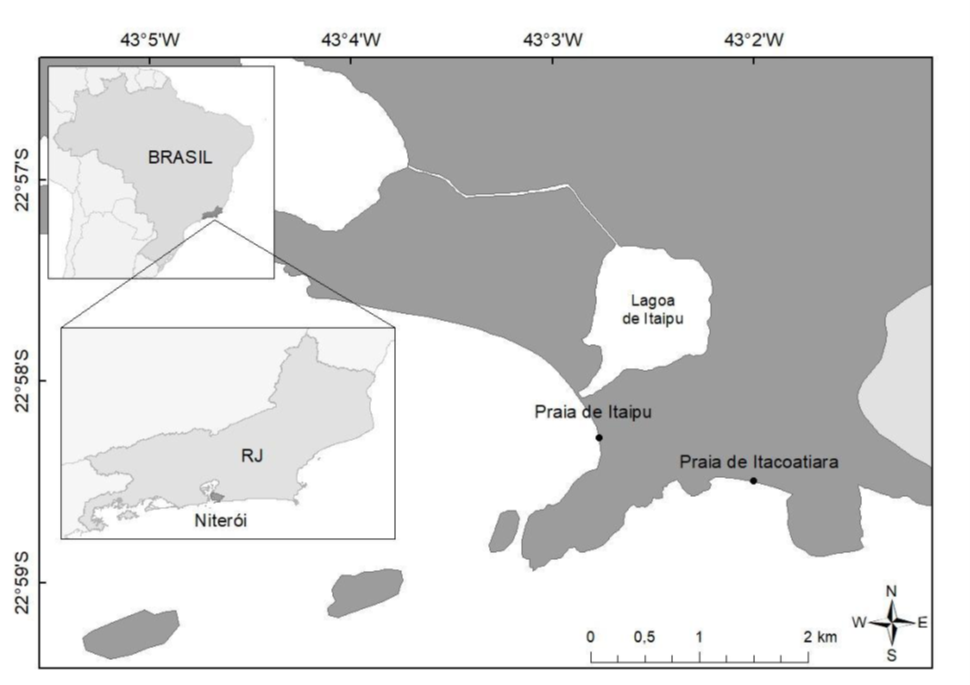

The study was performed in an artisanal fishing community in Itaipu beach, Niterói, metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, in the southeastern coast of Brazil (Figure 1). Itaipu beach is one of the most visited in the city, due to its calm waters, infrastructure of bars and restaurants and easy access by public transport. Fishermen's boats are laid out on the beach and the fish caught is sold on the spot.

The present study was carried out between May and July, 2016 by applying an open questionnaire (Table 1) in the form of an interview, to a total of 30 fishermen from the Itaipu region. The interviews were taken randomly, depending on fishemen’s availability and willingness to be interviewed. The questionnaire, was divided into two parts: one identifying the profile of fishermen, and other trying to analyze the perception of the interviewees individually and by comparing them. The research objectives were always explained at the beginning of each new interview to obtain consent from them (fishermen) (Costa-Neto, 2006; 2007), and also to they do not think they were dealing with an investigation by an environmental agency (De Azevedo Santos et al., 2010).

Table 1. Questionnaire applied.

Questionnaire |

| Local: Date: |

| Name: |

| Sex: F ( ) M ( ) Age: Schooling degree level: |

| 1- How many years have you been a fisherman? |

| 2- Have you ever heard about marine litter? |

| 3- Do you think it has been getting worse over time? |

| 4- What type of marine litter do you see frequently? |

| 5- What damage can marine litter cause to the environment? |

| 6- What damage can marine litter cause to your activity? |

| 7- Who do you consider responsible for the presence of litter on the beaches and at sea? |

| 8- Does your activity generate waste that can become marine litter? Which are? |

| 9- Could you minimize the production of this waste? |

| 10- Is the marine litter floating or in the sediment? |

| 11- Do you see an increase in marine litter at any time of the year? |

The result of the research was gathered and analyzed in two parts. At first, the respondents' answers were tabulated to calculate the percentages of answers for each question. In a second moment, it was highlighted, through citations, some of the different points of view of the interviewees, enriching the results showed through the graphs (Bay and Silva,2011).

Results

Fishermen profile

Twenty-nine of the interviewees (97%) were male and only 1 was a female, with ages ranging from 27 to 67 years. More than half (57%) were over 50 years old (57%) and of these, 44% were between 51 and 60 years old. Most (80%) have been working in the sea between 20 and 49 years (30

Discussion

Fishermen profile

The profile of fishermen in Itaipu is very similar to that of other traditional artesanal fishing communities in Brazil, with the majority of men over 50 years old, with little education and many years of activity (Carvalho, 2008; Oliveira et al., 2016).

According to Bavinck et al (2014), fishing is a male dominated activity mainly due to the need of the use of force at the capture activity. Traditionally, in fishing, women carry out activities that do not require the handling of heavy gear such as the capture of crustaceans and molluscs or processing fish (Vasconcellos et al., 2007)

The presence of few young people engaged in fishing activities is due to the low remuneration of this family artisanal fishing sector, which leads them to abandon the fishing activity as observed by Capelesso and Cazella (2011). Despite its historical value, this activity is at risk and may even disappear if there are no preventive measures. In addition to legal disputes involving attempts to remove the Itaipu fishermen community from the beach, pollution and large-scale fishing make it more difficult for fishermen to continue working every year, as stated by Jorge Nunes de Souza, president of Fishermen and Friends of Itaipu Beach Association in an interview. He also points out that, in the past, it was a tradition of the profession to pass from father to son. Today, many descendants of fishermen sought out other professions (Capelesso and Cazella, 2011). In Itaipu, young people from traditional fishing families end up working in the beach bars and restaurants (personal observation), some of which are owned by the families themselves.

In addition to age, schooling is highly relevant to the results of environmental perceptions, as awareness of environmental issues may be related to the level of education of respondents, since people with a college degree and post-graduates generally have higher access to research-related information (Aminrad et al., 2011). Concern with environmental issues is more common among people with a higher level of education; but less access to schooling does not mean greater complacency with disrespect for the environment, but perhaps greater ignorance and greater inability to express an opinion on these issues (CESOP, 2012).

As a counterpoint to the low education level prevailing among fishermen in Itaipu, the long time they have been working as a fisherman makes them more aware of the changes that have taken place at sea over the years of work. It is worth mentioning that we had the opinion of fishermen with a long-time fishing in the region, reaching 57 years of experience in the Z-7 fishermen colony.

Fishermen perception

Considering the number of simple and imprecise answers and the statements of some of the interviewees stating that marine litter is garbage that comes from the Guanabara Bay or brought in by the rains, it makes us think that the fishermen of Itaipu consider marine litter only those coming from sources that most affect them. However, as cited by Araujo (2003), marine litter is a generic term for all litter present in the sea and is not related to any specific origin. Statements such as ''It's what I see most every day'' suggests that some interviewees know that marine litter is not restricted to a specific source, as it is commonly seen in large quantities in the daily lives of these fishermen, corroborating data obtained by Silva et al. (2015) and Castro et al. (2020) when they studied macro and micro-waste on Itaipu beach, respectively. The large amount of marine litter is related to increasing consumption and poor waste management and has caused several consequences for fauna, tourism and human health, in addition to fishing, with losses of fishing nets, generated by a large amount of waste in the sea (Videla and Araujo, 2021). The relationship between the increase in the amount of marine litter and the increase in the population was also cited by Lebreton et al., (2017), where the authors state that the growing urbanization ends up generating a greater population concentration, which aggravates the problem of pollution in large cities, generating different types of waste that nature cannot absorb. This process ends up interfering negatively in the environment in which we live, including those close to the urban environment (Jambeck et al., 2015).

Ninety percent of respondents stated that the amount of marine litter has increased over time. Of these, 20% blamed this increase on dredging processes that took place in Guanabara Bay, an area close to the studied region. According to Lagedo (2014), the dredging process in the interior of Guanabara Bay has become more frequent over time due to the increase in port demand in the region. Fishermen's perception of the increase in garbage comes from the fact that the dredged sediment, full of residues, is thrown into an oceanic area close to the Itaipu region. This eviction, when carried out mainly at high tide, generates a cloud of pollution that ends up moving and sedimenting close to the coast, which can harm fishing (COMPANHIA DOCAS DO RIO DE JANEIRO - CDRJ, 2002). Some of the interviewees also added in their response, that the increase in the amount of marine litter has worsened in recent decades, mainly due to the increase in the amount of plastic, packaging, and disposables that are widely produced and consumed by the population in a practical way of life, as recorded by Bergman et al. (2015); which brings us to the quote of one of the interviewees:

“- Yes, the garbage is getting worse. It got worse after they stopped producing glass containers and everything became disposable.”

In the last 50 years, there has been a significant change in the amount of waste generated, due to the accelerated production of durable synthetic materials. The cult of 'disposable', a pillar of practicality in modern societies, has taken a high environmental cost. As shown in Geyer et al. (2017) 8.3 billion tons of plastic have been produced since the beginning of the mass production of this material, in 1950, until 2015. Most of it has already become waste and almost 80% of the material is now in landfills or in the environment (Geyer et al., 2017).

The fisherman's speech on the increase in pollution with the emergence of disposables, combined with that observed by the interviewees, confirm results observed in several studies carried out around the world that mention plastic as the most frequent marine debris (Chassignet et al., 2021). Goldberg already in 1995 talked about contamination by plastic materials as an emerging problem in coastal areas of the 21st century and Thief et al. (2003) about floating marine litter on the Pacific coast (Chile); both explaining the fact that marine plastic waste travels a long distance due to characteristics such as flotation and high durability. Silva et al. (2018) demonstrates a great concern about the theme, affirming in their work that the issue of pollution in coastal environments caused by solid residues, mainly plastic, is a major problem, and needs to be tackled with the collaboration of the whole society in with government agencies.

The second most cited item by respondentes was the garbage from vessels, including large industrial garbage, such as steel cable, tow, iron, chemical products, etc., which is not often mentioned in surveys of collections on beaches and coastlines, even because it is garbage that mostly does not reach the beach, being trapped in the high seas, floating or in sediment. This kind of garbage needs total attention, as according to United Nations (UN) estimates, about 30% of the waste that contaminates the oceans comes from accidents or discharges from ships, oil platforms and offshore incinerators (Geyer et al., 2017).

Itaipu fishermen´s understand that the biggest damage generated by marine litter is the impact on fish, with 50% of the answers focused on this topic. Among the consequences were cited higher mortality, change in the route of shoals and decrease in the quantity and quality of fish. Works such as De Azevedo Santos et al. (2010) show us that the quantity of fish in certain regions has been decreasing due to pollution. The amount of responses addressing only this topic, leaving the background, with 23%, the damage to the water quality itself or even to the rest of the fauna (remembered in 20% of the answers), shows us the little knowledge about the environment that these fishermen present. Bearing in mind that 20% of the interviewees did not know how to say what damage marine litter can generate in the environment, as in the answer below:

"- I don't know, I know it can harm my work"

Resende et al. (2011) state that in addition to harming the environment, artisanal fishing has been severely and directly affected by the impacts of this pollution, as also observed in our work on the answers to question 6. Material damage was the most mentioned since it directly affects the fisherman's earnings. Environmental issues such as the consequence of marine litter on fish, causing its reduction and consequent increase in fishing time were not mentioned as a priority, and the influence of marine litter on the health of fishermen even less. This same order of priority was observed by Timbó et al (2019) when they assessed the perception of bathers and merchants on this same beach. It should be noted that one of the consequences of marine litter is the dispersion of pathogenic microorganisms adhered to the biofilm that forms on its surface (Silva et al., 2019) and that can come into contact with fishermen when handling the litter that comes collected in fishing nets, causing injuries (Araujo et al., 2020).

Our results were also observed by Caldas (2007) when evaluating the opinion of users of Porto da Barra beach about the responsibility for the presence of marine litter, where 63% of the interviewees answered that the presence of garbage was due to a lack of awareness/education and 23% lack of collection structure, such as lack of dumpsters distributed by the beach and lack of regular cleaning. Cargo carriers, responsible for large vessels, were also mentioned, as many of the examples of marine litter cited by the fishermens are of foreign origin; which emphasizes what was said by UNEP (2005) when mentioning that among the maritime activities that generate marine litter are concentrated maritime transport, mining, drilling, and offshore extraction and illegal waste discharges at sea.

Most fishermen did not include themselves as a polluter, blaming companies, governmental or not and the population in general, but as already recorded in UNESCO (1994), waste left by small boats and by fishermen destroys the fauna and flora present on the beach and end up degrading reefs. Furthermore, these materials can break into smaller pieces of plastics, releasing microplastic to the environment, and keep as a "continous source" of microplastics in the oceans for a long time. Respondents also mentioned that artisanal fishing does not pollute, which is not confirmed in many studies that claim that fishing, navigation and other maritime activities, although on a smaller scale, are also responsible for the presence of marine litter (Galgani et al., 2015). Large numbers of lines, nets and other fishing devices are lost in the sea every day, not only contaminating the environment but posing serious risks to fish, birds, dolphins, and whales (Provender et al., 2016).

Some fishermen assumed the production of waste by fishing, mentioning the loss of net, hook, line and household waste, such as biscuit packages or plastic bags that they take on the vessel and are carried by the wind; which brings us to another very important topic, called ghost fishing.

As already mentioned, lost, discarded or abandoned fishing gear generates the mortality of marine species, which is called ghost fishing. These impacts on the environment and the ability of these materials, which are highly durable, to continue fishing cyclically in all parts of the marine environment today generates enormous concern (Lively and Good, 2019).

Some of the interviewees addressed the population's lack of education, to cite education as a measure to solve the problem of marine litter. As seen in Freitas and Maia (2009), transformative education, aimed at the social, professional and psychological is the best way to lead the population to understand the importance of maintaining natural resources, generating environmental awareness in the student.

Government actions as inspection and urban cleaning, encouraging recycling and the use of eco-barriers in the outflow of rivers were cited. According to Neto et al. (2011) the rivers near the Guanabara Bay region are highly urbanized and receive a large amount of waste, discarded by the riverside population. The large number of interviewees that do not see a solution to the problem of marine litter are noteworthy. Perhaps this is a reflection of their observation of the increase in marine litter over time, as mentioned by the vast majority of respondents. Although cited by few, the concern of institutions and social groups with the environmental conditions of the beaches has given rise to worldwide beach cleaning campaigns, such as the Clean-Up Day, which takes place in more than 75 countries, including Brazil, through the action of volunteers, who carry out the task of collecting garbage (Araujo, 2003). Silva et al. (2018), on the other hand, says that, although they are important, these campaigns are sporadic actions, therefore palliative and insufficient in the absence of permanent policies.

The answers regarding the location of marine litter, on sediment or water column, reflect the experience lived by fishermen daily. Of the interviewees who stated that there was a greater amount of marine litter in the sediment, the vast majority stated that they were unable to see the marine litter in the sediment, but considered the reports of divers who are always around the region or even the marine litter that often ends up being trapped in the nets, which impacts its activities. This result confirms some research that claims that the marine litter we see on our beaches is only a small percentage (15%) of all the marine litter that exists in the oceans. According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP, 2005), 15% of marine waste floats on the surface or is in the water column (more than 40 centimeters deep). The remaining 70% is on the seabed, out of sight. This statement can be intensified once they are non-biodegradable materials as stated in Neves (2013), since this waste can persist for many years on the seabed, mainly due to the absence or lesser intensity of processes that influence its degradation on land. Because the levels of oxygen dissolved in the greater depths are lower, as well as the solar radiation and the temperature, there is low intensity in the processes of thermal oxidation and photo-oxidation (Gewert et al., 2015).

As in Castro et al. (2020), the amount and composition of garbage deposited on the beaches also depend on seasonal variations, periods of rain and drought, dynamics of tidal currents, as well as beach cleaning practices. Differently from what was reported in the review of Videla and Araujo (2021), where several authors observe a greater amount of litter in rainy periods, most respondents stated that in winter they observe a greater amount of marine litter, relating this season to the sea currents that, affirmed by the interviewees, occur in greater quantity at this time, which ends up leaving the sea more agitated and consequently bringing the garbage from the bottom to the surface.

Relating the presence of marine litter on beaches with sea currents is a subject seen in some studies, such as in Oliveira et al. (2011), who claim that local drift currents can play the role of remobilizing waste. Following the idea of a greater garbage dump brought by the currents, but in this case taking into account a greater amount of rain, 33% of fishermen said they found a greater amount of garbage in the summer, which agrees with Neto and Fonseca (2011) when they claim that in the summer period, together with the heavier rainfall, the concentration of materials with greater mobility also increases, such as bags, cups, straws and plastic bottles, which become the majority of quantified artifacts on beaches. These materials are normally deposited at low tide, showing that they are materials from distant sources or, in some cases, left by bathers.

Conclusion

The analysis of the responses based on the fishermen's opinions allowed us to assess the perception that this group has about one of the serious environmental problems related to the marine environment with which they live on a daily basis.

Studies with environmental perception are intended through solutions proposed by the quantitative and qualitative analyzes of these studies, to raise awareness and make the individual understand environmental issues that they experience. Thus, new methodologies can be created and analyzed based on the experience and results obtained (Freitas and Maia, 2009).

Although the number of interviewees represents 20% of fishermen in Itaipu, the results indicated that despite observing the growing pollution of the environment where they work and identifying the main pollutant, most of the interviewees point out as a consequence of this pollution the influence on their work, without demonstrating the environmental concern as a whole, exempting themselves from guilt to responsibility for part of this pollution found in the marine environment; pollution that can cause a lot of damage to the environment such as ghost fishing.

This study was important to understand the behavior of fishermen facing the issue of marine litter and the various forms of its influence in each case. The perception/data gap is an important element of designing an education program to engage stakeholders in this issue.

Fishermen are directly affected by marine litter and are also one of the sources of this problem. Any marine litter mitigation program must rely on this social group. So based on the results of this study, there is a need for educational actions to be carried out with fishermen from the Z-7 colony in Niterói (Itaipu) aimed at raising their awareness, aiming at maintaining the quality of the environment and enabling them as disseminators of good environmental practices.

Considering the government actions cited by them as ways to mitigate the problem of marine litter, other activities should be done as more government incentives on this issue (e.g., weight of garbage collected in the sea and brought by fishermen could be result in tax reduction to them), greater supervision during fisheries, some incentive to recycle fishing nets, etc)

Further studies on the topic must be realized covering fishing communities from other locations to provide more results for decision makers mitigate this problem.

Acknowledgement

We thank the fishermen of colony Z7 in Itaipu, Niterói, RJ, Brazil, for their willingness to answer our survey

Author Contribution

Fernanda Vasconcelos was responsible for Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Roles/Writing - original draft; Writing - review & editing and Fábio Vieira de Araujo was responsible for: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing - review & editing.

References

- A TRIBUNA RJ, (2020). Avaiable at https://www.atribunarj.com.br/cadastro-de-pescadores-na-praia de-itaipu/23 , Access in july 2022

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - AMINRAD, Z.; ZAKARIA, S. Z. B. S. & HADI, A. S., (2011). Influence of age and level of education on environmental awareness and atitude: case study on Iranian students in Malaysian Universities, The Social Sciences, 6 15-19.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - ARAUJO, M. C. B. & COSTA, M. F., (2003). Lixo No Ambiente Marinho, Revista Ciência Hoje, 32 (191), 64 – 69.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - ARAUJO, F. V.; CASTRO, R. C.; SILVA, M. L. & SILVA, M. M., (2020). Ecotoxicological effects of microplastics and associatedpollutants. On Aquaculture toxicology. Ed.Londres: Elsevier, p. 189-227.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - BAVINCK, M.; CHUENPAGDEE, R.; JENTOFT, S. & KOOIMAN, J., (2014). Governability of Fisheries and Aquaculture: Theory and Applications. Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg, New York, London.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - BAY, A. M. C. & SILVA, V. P., (2011). Environmental perception of residents of the Neighborhood of Liberdade de Parnamirim/RN about sanitary sewage, Holos, 3, 97 – 112.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - BERGMAN, M.; GUTOW, L.& KLAGES, M., (2015). Marine anthropogenic litter. Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg, New York, London.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - BLAIR, R. M.; WALDRON, S.; PHOENIX, V. & GAUCHOTTE-LINDSAY, C., (2017). Micro and nanoplastic pollution of freshwater and wastewater treatment systems, Springer Science Reviews, 5, 19–30.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - BURNS, E. E., & BOXALL, A. B. A., (2018). Microplastics in the aquatic environment: Evidence for or against adverse impacts and major knowledge gaps. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CAPELESSO, A. J. & CAZELA, A. A., (2011). Artisanal fishing between economic crisis and socio-environmental problems: Case study in the municipalities of Garopaba and Imbituba (SC), Environment and Society, 14 (2), 15 – 36.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CALDAS, A.H.M., (2007) - Analysis of the disposal of solid waste and the perception of users in coastal areas – a potential for environmental degradation. Post-graduation monograph, 60p., Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, BA, Brazil.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CARVALHO, A.R., (2008). Profits and social performance of small-scale fishing in the Upper Paraná River floodplain (Brazil), Brazilian Journal of Biology, 68(1): 87-93

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CASTRO, REBECA OLIVEIRA; SILVA, MELANIE L.; MARQUES, MÔNICA REGINA C. & ARAUJO, F. V., (2020). Spatio-temporal evaluation of macro, meso and microplastics in surface waters, bottom and beach sediments of two embayments in Niterói, RJ, Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 160, 111537.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CDRJ, COMPANHIA DOCKS OF RIO DE JANEIRO, (2002). Environmental Impact Study - EIA. Dredging Project of the Access Channel and the Evolution Basins of the Terminals of the Port of Rio de Janeiro and Niterói.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CESOP, CENTER FOR PUBLIC OPINION STUDIES, (2012). Brazilians' perception of the environment between 1990 and 2010, Tendências, 18 (2), 537-550.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - CHASSIGNET, E. P., XU, X. & ZAVALA-ROMERO, O., (2021). Tracking Marine Litter with a Global Ocean Model: Where Does It Go? Where Does It Come From? Frontiers in Marine Science, 8.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - COSTA-NETO, E. M., (2006).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - COSTA-NETO, E. M., (2007). The freshwater crab, Trichodactylus fluviatilis (Latreille, 1828) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Trichodactylidae), in the conception of the residents of the village of Pedra Branca, Bahia, Brazil, Biotemas, 20 (1), 59-68.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - DE AZEVEDO SANTOS, V. M., NETO, E. M. C. & DE LIMA STRIPARI, N., (2010). Conception of artisanal fishermen using furnas reservoir, State of Minas Gerais, about fishing resources: an ethnoictiological study, Biotemas, 23 (4), 135-145.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - FRENCH; J. R. S. R. & MAIA; K. M. P., (2009). A Study of Environmental Perception among Students of Youth and Adult Teaching and 1st Year of High School of the Counting Teaching Foundation (FUNEC) - MG, Revista Synapse Ambiental, 6 (2), 52 – 77.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - GALGANI, F., HANKE, G., & MAES, T., (2015). Global distribution, composition and abundance of marine litter. In M. Bergmann, L. Gutow, & M. Klages (Eds.), Marine anthropogenic litter (pp. 29–56). Berlin: Springer.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - GALL, S. C. & THOMPSON, R. C.,(2015). The impact of debris on marine life, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 92, 1–2, 170-179.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - GEWERT, B.; PLASSMANN, M. M. & MACLEOD, M., (2015). Pathways for degradation of plastic polymers floating in the marine environment, Environmental Science: Processes Impacts, 17, 1513-1521.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - GEYER; R.; JAMBECK; J. R. & LAW; K. L., (2017), Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made, Science Advances, 3 (7).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - GOLDBERG, E.D., (1995). Emerging problems in the coastal zone for the twenty-frist century, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 31 (4-12), 152-158.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - JAMBECK, J. R., GEYER, R., WILCOX, C., SIEGLER, T. R., PERRYMAN, M., ANDRADY, A., NARAYAN, R. & LAW, K.L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into our oceans. Science, 347, 6223, 768-771.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - LAGEDO, F.B. (2014), Imaging through the use of lateral scanning sonar in boot-off regions in Guanabara Bay. Graduation monograph (Geophysics). Fluminense Federal University, Niterói.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - LIVELY, J. A. & GOOD, T. P., 2019. Ghost Fishing. On World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition), Academic Press, 183-196.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - KOWALSKI, A. & JENKINS, L., (2021). A review of primary data collection on ghost fishing by abandoned, lost, discarded (ALDFG) and derelict fishing gear in the United States. Academia Letters.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - LAIST, D.W., (1987). Overview of the biological effects of lost and discarded plastic debris in the marine environment, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 18, 319–326.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - LEBRETON, L. C. M.; VAN DER ZWET, J., DAMSTEEG, J-W, SLAT, B., ANDRADY, A. & REISSER, J. (2017). River plastic emissions to the world's ocean. Nature Communications, 8, 15611.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - LINK, J., SEGAL, B., & CASARINI, L. M., (2019). Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear in Brazil: A review. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - MATSUOKA, T.; NAKASHIMA, T. & NAGASAWA, N., (2005). A review of ghost fishing: scientific approaches to evaluation and solutions, Fisheries Science, 71(4), 691-702.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - NEVES, R.C.; SANTOS, L.A.S.; OLIVEIRA, K. S.S.; NOGUEIRA, I.C.M.; LAUREL, D. V.; FRANCO, T.; FARIAS, P.M.; BOURGUINON, S.N.; CATABRIGA, G. M.; BONI, G. C. & QUARESMA, V. S., (2013). Qualitative Analysis of Garbage Distribution in Barrinha Beach (Vila Velha - ES), Integrated Coastal Management Magazine, 11(1), 57-64.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - NETO, J. A. B. & FONSECA, E.M., (2011). Seasonal, spatial and compositional variation of garbage along the beaches of the eastern bank of Guanabara Bay (Rio de Janeiro) in the period 1999-2008, Journal of Integrated Coastal Management, 11(1), 31-39.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - OLIVEIRA, A.L.; TESSLER, M. G. & TURRA, A., (2011). Distribution of garbage along sandy beaches - Case study in Massaguaçu Beach, Caraguatatuba, SP, Integrated Coastal Management Journal, 11(1), 75-84.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - OLIVEIRA, P. B., BULHOES, A., ZAPPES, E. & CAMILA, H., (2016). Artisanal fishery versus port activity in southern Brazil. Ocean & Coastal Management, 129, 49-57.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - ORLANDI, N., ARANTES V. & BARRELLA, W., (2015). The solid residues found in santos beach- SP, BioScience, 4 (2), 83 - 89.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - PAHL, S., WYLES, K. J. & THOMPSON, R. C., (2017). Channelling passion for the ocean towards plastic pollution. Natural Human Behavio,1, 697–699.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - PINTO, R., 2010. Itaipu Stories. Itaipu Beach. Blogspot.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - PROVENCHER, J, BOND A. L., AVERY-GOMM, S., BORRELLE, S. B., BRAVO-REBOLLEDO, E. L., HAMMER, S, KÜHN, S., LAVERS, J. L., MALLORY, M. L., TREVAIL, A. & VAN FRANEKER, J. A., (2016). Quantifying ingested debris in marine megafauna: a review and recommendations for standardization. Analitycal Methods 9:1454–1469.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - RESENDE, A.T.; SILVA, C. A. & FERREIRA, J. The., (2011). Clean Bay Project: Monitoring of Marine Environments Degredados by Solid Waste in Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Integrated Coastal Management Magazine, 11(1), 103-113.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - ChneiDER S, T., (2009). Ghost fishing in the seas, Revista Ciência Hoje, 43(257), 62- 63.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - SILVA, M. L.; ARAÚJO, F. V.; CASTRO, R. O. & SALES, A. S., (2015). Spatial-temporal analysis of marine debris on beaches of Niterói, RJ, Brazil: Itaipu and Itacoatiara. Marine Pollution Bulletin., 92, 233-236.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - SILVA, M. L.; CASTRO, R. O.; SALES, A. S. & ARAÚJO, F. V., (2018). Marine debris on beaches of Arraial do Cabo, RJ, Brazil: An importante coastal tourist estination, Marine Pollution Bulletin,130, 153–158

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - SILVA, M. M.; MALDONADO, G. C.; CASTRO, R. O.; MEIGIKOS, R & ARAUJO, F. V., (2019). Dispersal ofpotentially pathogenic bacteria by plastic debris in Guanabara Bay, RJ, Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 141,561-568.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - THIEF, M.; HINOJOSA, L.; VASQUES, N.; MACAYA, E., (2003). Floating marine debris in coastal waters of the SE-Pacific (Chile), Marine Pollution Bulletin, 46(2), 224-31.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - TIMBÓ, M.; SILVA, L.M.; CASTRO, R. C. & ARAUJO, F. V., (2019). Diagnosis of the environmental perception of users of itaipu and itacoatiara beaches regarding the presence of solid waste. Revista de Gare Costeira Integrada, 19, 157-166.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - TUDOR, D.T. & WILLIAMS, A., (2003). Public Perception and Opinion of Visible Beach Aesthetic Pollution: The Utilisation of Photography. Journal of Coastal Research. 19. 1104-1115.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - UNEP, 2005. Marine Litter, an analytical overview. Nairobi (Quénia).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - UNESCO, Marine Debris: Solid Waste Management Action Plan for the Wider Caribbean. IOC Technical Series 41, Paris, 1994.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - VIDELA, E. S. & ARAUJO, F. V., (2021). Marine debris on the Brazilian coast: which advances in the last decade? A literaturereview. Ocean & Coastal Management, 199, 105400.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - WAP, World Animal Protection, (2022).

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - WERNER, S., BUDZIAK, A., VAN FRANEKER, J., GALGANI, F., HANKE, G., MAES, T., MATIDDI, M., NILSSON, P., OOSTERBAAN, L., PRIESTLAND, E., THOMPSON, R., MIRA VEIGA, J. & VLACHOGIANNI, T. (2016). Harm caused by Marine Litter.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar - ZAPPES, C.A.; OLIVEIRA, P. C.; DI BENEDITTO, A. P. M., (2016). Perception of fishermen from the north of Rio de Janeiro about the viability of artisanal fishing with the implementation of port mega-enterprises. Bulletin of the Fisheries Institute. São Paulo, 42(1), 73-88.

View at Publisher | View at Google Scholar